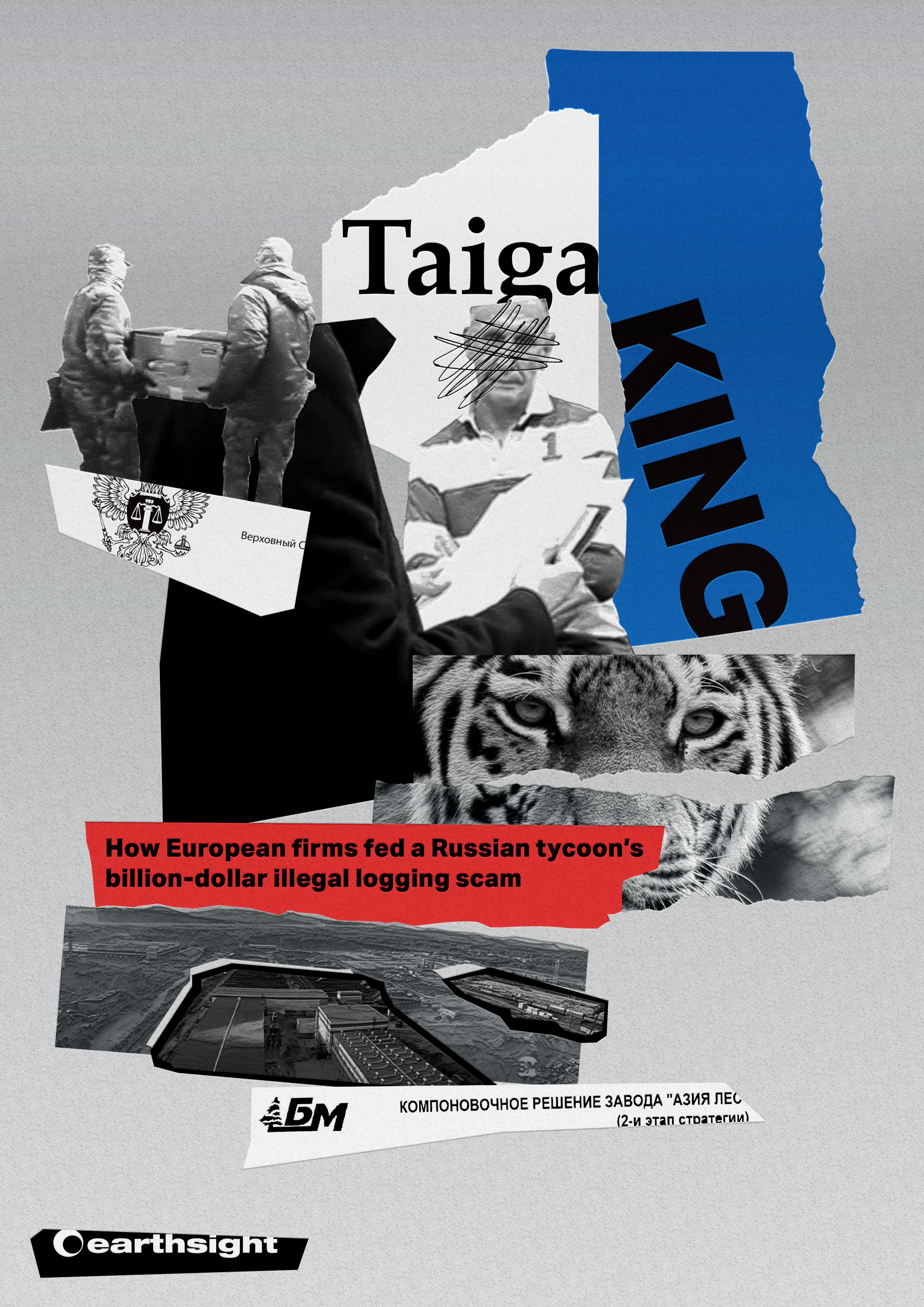

This is Evgeny Bakurov

Over the last decade, his companies cut down enough trees to build a near full-scale replica of the Great Pyramid of Giza

The wood came from protected forests in Russian Siberia

It ended up as children's furniture sold in Ikea stores around the world

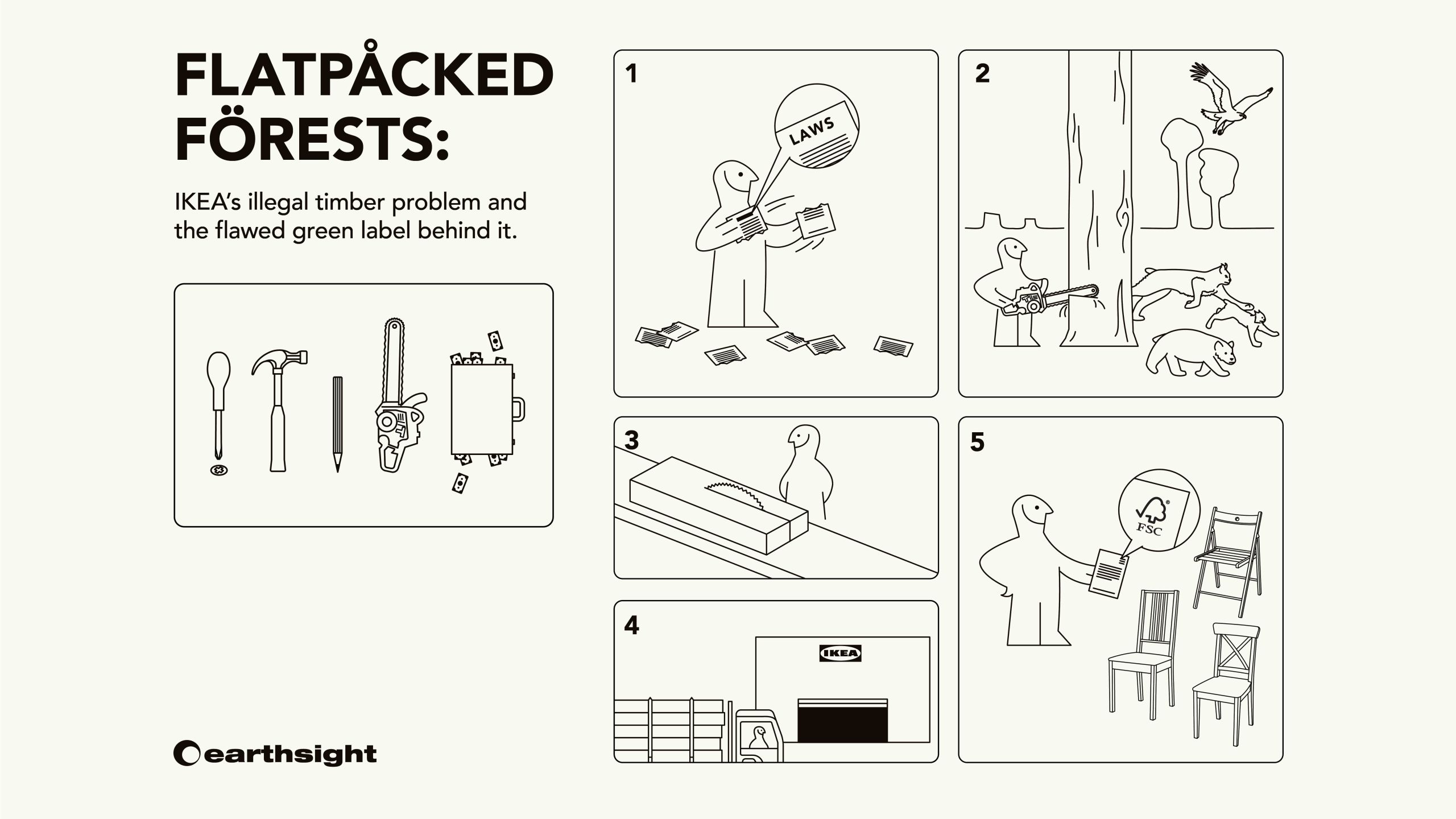

Earthsight's year-long investigation reveals how this happened...

And who's responsible.

Key findings

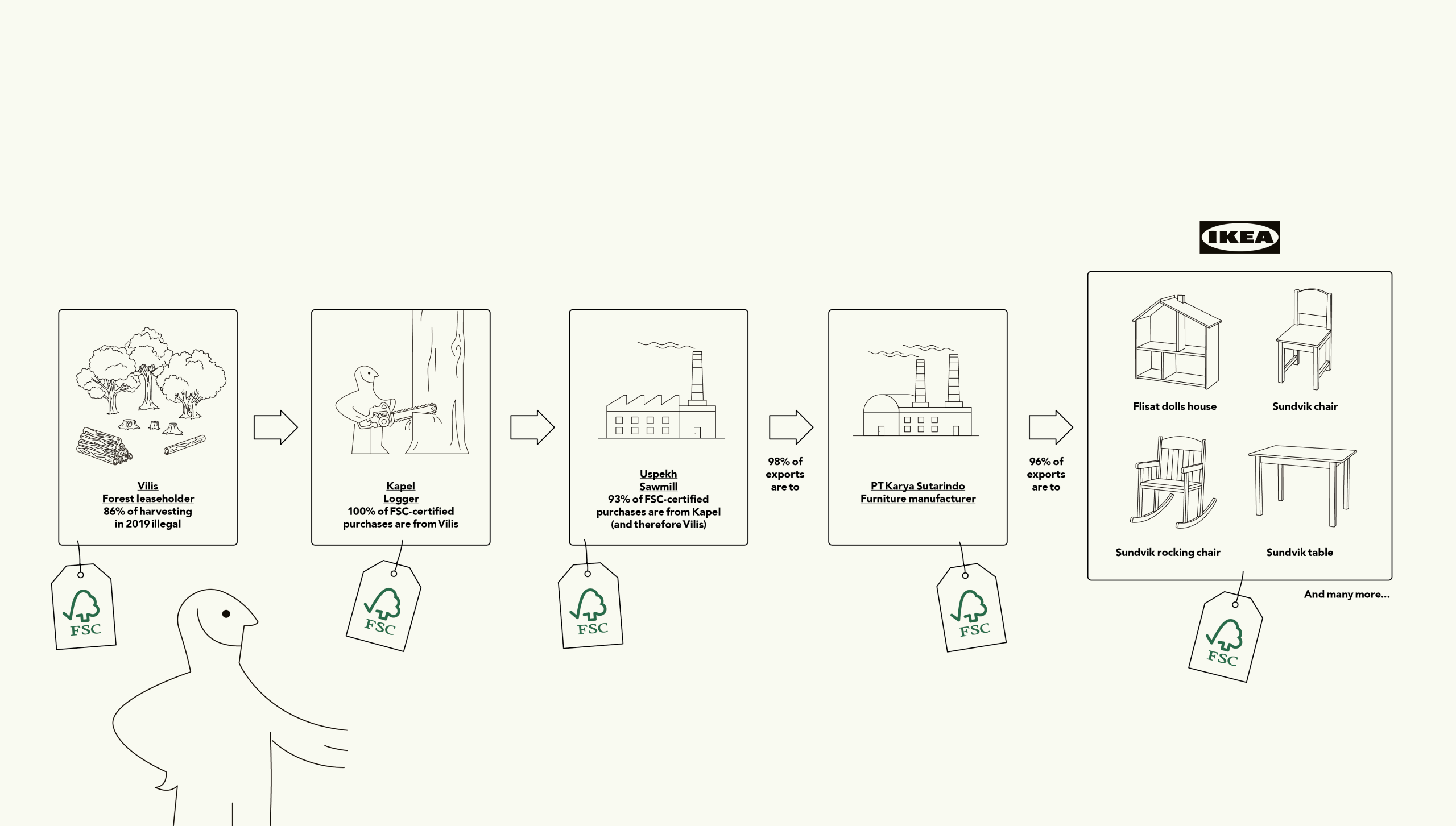

- Ikea, the world's biggest furniture retailer, has for years sold children's furniture made from wood linked to vast illegal logging in protected forests in Russia, an Earthsight investigation has found. It is one of a number of western firms linked to the case.

- The brand's popular Sundvik children's range – which includes chairs, tables, beds and wardrobes – and Flisat doll's house are among the items likely tainted with illegal wood. Earthsight estimates that shoppers have been purchasing an Ikea product containing the suspect Russian lumber somewhere on earth every two minutes.

- Using undercover meetings, visits to logging sites, satellite imagery analysis and scrutiny of official documents, court records and customs data, we traced wood furniture on sale in Ikea stores around the world to forests in remote Siberia. They're controlled by companies owned by one of Russia's top-50 wealthiest politicians, Evgeny Bakurov.

- Our year-long investigation found that Bakurov's businesses broke numerous forestry and environmental laws. Illegal deals helped them harvest 2.16 million cubic metres of wood in protected forests over the last decade. Piled high, the logs produced would rival the Great Pyramid of Giza.

- Loggers felled millions of trees on the false pretext they were dead, dying, diseased or damaged – what's known as sanitary felling. Sick trees are often used as an excuse to flout Russia's logging laws.

- Bakurov's pine was certified by the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading global scheme for sustainable wood products, and shipped to an Indonesian manufacturer which supplies Ikea stores in countries including the US, UK, Germany, France and other European countries. Bakurov also supplied the retail giant through middlemen in Russia and China.

- Bakurov's tainted wood is also in many other supply chains heading to Europe and the US, aside from Ikea's. A majority of the EU's imports from eastern Russia are potentially contaminated.

- Earthsight holds FSC largely responsible for the logging abuses linked to Ikea and other retailers we connected to the scandal. They rely on the green label and its competitor PEFC to ensure their supplies are sustainable and legally sourced. Our findings provide further proof that this trust is wildly misplaced.

- FSC audits did not mention the rampant illegal logging documented by Earthsight and Russian authorities. Instead, high-risk wood continued to be sold in Ikea stores year after year.

- The findings show that governments in the US and Europe must enforce timber import laws more rigorously to address their roles in driving global deforestation.

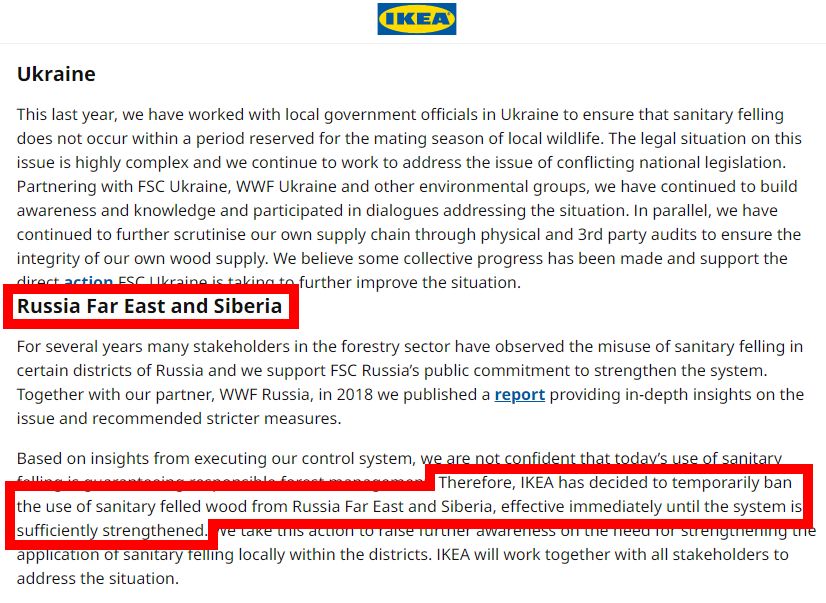

- Ikea, which denies wrongdoing, announced a temporary ban on sanitary felled wood from Siberia and the Russian Far East after Earthsight got in touch. The retailer insists Bakurov's wood was "legally harvested" – but recently dropped his companies as suppliers, citing unspecified "practices of concern".

Prologue

The noise was deafening: a lumbering, wood-munching machine carving through the forest like a knife through butter. Trees in the Siberian province of Irkutsk Oblast had grown slowly, weathering biting winds and frozen winters for over a century. Under the mechanical grip of the Ponsse CTL harvester, they fell within seconds.

As the half-million-dollar machine automatically stripped the trunks of branches and sawed them into logs, Evgeny Bakurov looked on with satisfaction. Heavyset with closely cropped hair, the 44-year-old has the appearance of a heavyweight boxer. The rare visit into the taiga, to the forefront of his logging operation, made a welcome distraction from his usual milieu, hobnobbing with local business leaders and posing for photo-ops.

Evgeny Bakurov. Source: Irk.gov.ru

Evgeny Bakurov. Source: Irk.gov.ru

Control of an area of forest the size of Greater London has given him plenty. His own private helicopter, a boat named after his daughter, multiple properties and an income putting him in the top 50 highest-earning politicians or bureaucrats in Russia.

It has not been easy. Extracting profit from these woods is hard – or at least it would be, if you followed the law, which is supposed to ensure that rights to log are sold competitively at auction, that logging rates remain sufficiently low to allow the slow-growing forest to recover, and that the most ecologically important tracts are kept largely off limits.

But Bakurov, a businessman-politician whose macho image and penchant for martial arts draw obvious comparisons to the Russian President he so admires, has learned not to worry about the law. For over the course of a long career, Bakurov has mastered the tricks of his trade, which in the world of Russian forestry have little to do with efficient business practices. It is about cultivating allies. A few campaign donations can go a long way.

Bakurov aboard a helicopter flying over the Russian taiga. Source: ExportLes / Julia Kiseleva / YouTube

Bakurov aboard a helicopter flying over the Russian taiga. Source: ExportLes / Julia Kiseleva / YouTube

In his case this is hardly a secret. His companies left a long paper trail laying bare widespread illegal logging, including in protected forests.

Finding a market for all this wood, with the nearest coast a thousand miles away, has also been challenging. Doubly so given its illegal origin. But Bakurov has had a couple of powerful corporate allies overseas too, from distant Sweden and Bonn.

Thanks to them, it turns out, a trail leads from Bakurov's remote Siberian forest destruction to children's bedrooms all over the world. It is part of millions of people's 'Wonderful Everyday'.

1. Siberia burning

Taming the taiga

Russia is one of the world's largest timber exporters and producers. In 2019, the former superpower overtook Canada to export more softwood lumber than any other country, and was on course to ship nearly a quarter of traded timber globally.

An incredible wealth of woodlands bless the country. Treetops cover nearly half of it, or more than 800 million hectares, knitting together Arctic tundra and vast eastern steppes in a tapestry of branches forming the largest forest on earth.

Europe and China form the biggest markets for this bounty. An increasingly throwaway culture, plus a rapid shift towards wood-fuelled electricity production and depleted domestic forests, have made Europeans turn to their giant neighbour to satisfy their hunger for cheap wood. European Union (EU) imports of logs, lumber, pulp, paper and other wood products from Russia are up 42 per cent in the last decade, nearing €3 billion per year.

In spite of the global economic shock caused by the Covid-19 (coronavirus) pandemic, this trade with the EU continued to grow last year, hitting a record high of 14.1 million tonnes – an amount which required the felling of approximately 200,000 trees per day.

"It may not be as high profile as Amazonian or Indonesian rainforest but the Russian boreal forest is hugely important"

In fact, the amount of Russian wood being consumed in Europe and many other countries is even larger than their direct imports suggest. That is because much of the Russian logs and lumber trundling across the border into China, the world's largest importer of timber, are re-exported, entering lucrative markets like Europe and the United States after being processed into finished goods like furniture and hardwood flooring. The US is the leading destination for wood product exports from China, valued at more than $9 billion in 2018.

While the European portion of Russia offers a ready supply of cheap wood, a significant share of exports come from Siberia and the Russian Far East.

Within these regions sprawls boreal forest or taiga, home to brown bear, wolves, elk and sable (a weasel-like mammal whose image adorns flags and coats of arms in Siberia). Here, the endangered Siberian Tiger, the world's largest, slinks silently between the tree trunks while flying squirrels leap and dart overhead. Sharp eyes may spot a white-tailed eagle soaring above the canopy, one of the largest living birds of prey.

"It may not be as high profile as Amazonian or Indonesian rainforest but the Russian boreal forest is hugely important," Nikolay Shmatkov, the former director of WWF Russia's Forest Programme, said in 2018. "It's crucial in regulating global climate – its trees, soils and peat store more carbon than all tropical and temperate forests combined – and are home to many large animals like forest reindeer that are disappearing from transformed and degraded forests."

The forests form a habitat for many, a lifeline for all – and they're dying.

Wildfires and climate change

Analysis by Global Forest Watch found that Russia lost 69.5 million hectares of tree cover since 2001. That's an area of forest the size of Texas. The land lost each year keeps getting bigger, with average annual losses in the 2010s double that of the previous decade. Last year was the second worst year on record for tree cover loss, according to the analysis.

Much of this deforestation is temporary. Unlike in the tropics, logging in boreal forests like those of Russia and Canada commonly involves the complete clearance (clearcutting) of chunks of forest which are then allowed to regrow. But even when such regrowth is taken into account, the data are stark. During 2001-12, Russia lost 36.5 million hectares but regained only 16.2 million hectares – a net loss of more than 20 million hectares.

"The main threat to Russian forests is the 'one-off' forest management model, in which the forest is used as a timber deposit, without efficient forestry," Alexey Yaroshenko, head of Greenpeace Russia's forestry department, told Earthsight. "In the vast majority of cases, the logged areas are simply abandoned to the mercy of fate without real concern about what will later grow on them."

With the remaining woodlands becoming increasingly degraded and fragmented, swathes of unbroken woodlands that scientists call 'intact forest landscapes' (IFLs) – each at least 500 square kilometres (or 70,000 football pitches) in size – break into shrinking archipelagos. Previously, the scale of IFLs ensured human impact was minimal. Torn apart, their native animal and plant life and natural processes are left exposed. Global Forest Watch analysis shows the vast majority of this forest loss is happening in eastern Russia, within the Russian Far East and Siberia.

The biggest cause of tree cover loss: fire.

"About 90 per cent of forest fires in Russia are caused by humans (I think that in reality it is even more)"

Fuelled by unusually hot conditions, colossal wildfires have been burning across Siberia, releasing record amounts of greenhouse gases. Choking clouds of ash and soot engulfed four Siberian regions in 2019, prompting a state of emergency and mobilising the military to help in firefighting efforts. The prolonged heatwave which hit the region in 2020, meanwhile, was "effectively impossible" without human-driven climate change, experts found.

More heat means more flames, which mean more permafrost melting and harmful gases released. And so the downward spiral continues.

Studies show increased logging activity in the Russian Far East and Siberia has also led to more frequent fires. Timber harvesting and logging roads fragment forests and make blazes more intense. The dried-out waste wood that loggers leave behind can act as tinderboxes, turning surface flames fuelled by leaf litter and low-lying vegetation into infernos that consume the whole canopy.

Yaroshenko said wildfires and loggers emboldened by weak official oversight are "acting together" to deplete Russia's forests and push logging into remaining reserves.

"It is generally believed that about 90 per cent of forest fires in Russia are caused by humans (I think that in reality it is even more)," he added. "A significant part of fires caused by humans are associated with hazardous practices in agriculture and forestry: the burning of logging residues during a dangerous period, the so-called 'controlled burning', which are often carried out without the necessary fire safety measures.

"In our experience, this is more [a result of] foolishness and carelessness than malice. We very often see fires occurring in felling sites or in the immediate vicinity of them."

Illegal logging hotspots

Widespread corruption among Russian politicians and the state officials in their pocket undermines good governance of forests. Logging is lucrative work, and a particularly important source of patronage and cash in the Russian Far East and Siberia. Even Russian president Vladimir Putin decried the "very corrupt" forestry industry during his annual news conference in 2019. The same year, the federal accounts chamber admitted that measures to tackle illegal logging "do not affect" the situation on the ground.

According to Greenpeace Russia's Yaroshenko, the Russian state has mounted a large campaign against illegal logging, but only in the narrowest sense of the term: commercial logging carried out without permits, which accounts for a small fraction of Russia's total annual timber production. He points out that "legal" or licensed felling often skirts the law, takes place on false or questionable grounds and results in the same devastating environmental impact as this unauthorised logging, but is far more common.

"Licensed or 'legal' logging in Russia often skirts the law"

The fact that large volumes of high-risk and illegally sourced wood from Russia end up in key consumer markets like the United States, EU and Japan is well documented. Despite some headline-making successes, however, such as a record $13 million fine issued for illegal Russian oak flooring found in the US, import laws in these countries meant to catch them don't seem to be working.

When the European Timber Regulation (EUTR), the bloc's flagship law on timber imports, came into effect in 2013, studies suggest that nearly as much stolen wood was entering its member states from Russia as from all tropical countries combined. Three years later, an EU-commissioned review of the legislation noted Russia was an increasingly prominent source of illegal wood, alongside Ukraine and Belarus. Guidance on EUTR made on the bloc's behalf identifies the Russian Far East and Siberia as hotspots for illegal logging.

In December 2020, Earthsight revealed how 100,000 tonnes of timber linked to Russia's largest illegal logging scandal this century had entered Europe. Our report noted that the case, though large, was unlikely to be exceptional. We were already researching yet another Russian logging scandal, and busy unearthing another route for suspect wood to leave the country.

Russia's illegal logging capital

The threats facing the Russian taiga – corruption, climate change, illegal logging – are most pronounced in Irkutsk oblast (province). Occupying an area almost twice the size of California, the Siberian heartland in east-central Russia is the country's largest producer of logs and lumber. It is characterised by broad valleys and rolling hills carpeted with dense forests of larch, pine, fir, spruce, aspen and birch.

The major railway connections in the province offer an easy means of dispatching huge numbers of logs to major ports and processing centres, including those in China. With quick money to be made, it's no surprise that the region has witnessed some of Russia's worst deforestation rates. More than a quarter of the net forest loss seen in Russia in the first 12 years of this century occurred in Irkutsk.

Irkutsk Oblast (red) in Russia. Image: Ezhiki / Wikimedia Commons (licensed under CC BY 2.5)

Irkutsk Oblast (red) in Russia. Image: Ezhiki / Wikimedia Commons (licensed under CC BY 2.5)

In Russia as in most heavily forested countries where it occurs, illegal logging is far from a clandestine activity. It is undertaken not by individuals but by large companies, using modern machinery. And it happens in plain sight, under the cover of legitimate harvesting. The wood is already laundered before the tree hits the ground.

In the former Soviet world, the most common ruse these companies use to illegally harvest and launder wood is 'sanitary' felling. Forestry regulations meant to ensure that cutting does not harm the forest can be circumvented on the grounds of stopping the spread of disease or pests. Companies abuse these rules to allow them to cut far more trees, in a far more destructive manner, than their logging licenses allow (see 'Russia's problem of illegal sanitary logging').

Russia's problem of illegal sanitary logging

Sanitary logging, also called salvage logging, is a common cover for illegal deforestation in Russia.

Click here to read more

Alexey Yaroshenko of Greenpeace Russia told Earthsight as much as 90 per cent of recorded sanitary logging in the country is "pseudo-sanitary", or carried out on false or questionable pretexts. This is supported by studies such as one by WWF in 2019, which found that 96 per cent of the planned sanitary felling sites it examined had been allocated improperly.

It is a big red flag, then, that Irkutsk oblast regularly produces more timber through sanitary felling than anywhere else in Russia. The province has a high-profile history of abusing these rules, and those charged with enforcing them a long history of turning a blind eye. In 2019, Irkutsk's top forestry official, Sergey Sheverda, was arrested for facilitating the illegal felling on false sanitary grounds of woodland in a nature reserve.

Irkutsk forest chief Sergey Sheverda, arrested in 2019 for facilitating illegal sanitary felling. Photo: Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation

Irkutsk forest chief Sergey Sheverda, arrested in 2019 for facilitating illegal sanitary felling. Photo: Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation

2. The heist

Evgeny Bakurov, logging baron

Evgeny Bakurov, 44, is not everyone's picture of a typical civil servant. His stocky frame and penchant for self-promotion differ dramatically from the stereotype of faceless pencil-pushers trudging up and down the corridors of power. As does his apparent fondness for being photographed shirtless.

The elected member of Irkutsk Oblast's legislative assembly ranked 44th on a Forbes list of Russia's highest-earning civil servants or legislators in 2019, with a declared income of 365 million roubles (more than $5 million). His most recent declaration of assets included 71 plots of land and a Gazelle AH Mk 1 military helicopter.

Climbing high above the treetops, roaring into the taiga, his chopper offers spectacular views of the source of Bakurov's wealth: wood. Bakurov is well-known locally for controlling the ExportLes (Russian for "Export Forest") group of forestry firms (see 'The Bakurov empire'), whose forest leases span an area bigger than London. He also serves as president of the region's timber trade body.

Evgeny Bakurov ranked 44th on a Forbes list of Russia's highest-earning civil servants or legislators in 2019. Source: Forbes.ru

Evgeny Bakurov ranked 44th on a Forbes list of Russia's highest-earning civil servants or legislators in 2019. Source: Forbes.ru

If the 2016 promotional video for the ExportLes group is to be believed, Bakurov is a responsible, if eccentric, guardian of nature. It features close-ups of certificates issued to his companies by a global body that vets wood suppliers, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), and shots of his workers combatting wildfires. Other, more unconventional footage sees Bakurov boxing and swinging shirtless on an exercise bar.

Perhaps inspired by Russian President Vladimir Putin, Bakurov is known for macho stunts. Take the YouTube video of him posing for tourists' cameras wearing only a pair of red swimming shorts. Or his profile on VK, the social media platform popular in Russia, which features a picture of him beside a chained tiger. Or his honorary chairmanship of the local Shotokan karate club, for which, according to a recent profile in Russian publication Verblud V Ogne, he rarely trains but promotes locally and to which he "provides material assistance".

There is also the documentary about his World War II veteran grandfather Vladimir, screened at Evgeny's expense in several Russian cities, in which the pair's lavishly shot boating trip serves as another excuse for Evgeny to bare his torso.

"People like me don't drown," the grandson declares before jumping into the water to showcase his butterfly stroke. His political career, so far, has proved him right.

The Bakurov empire

In public promotions fronted by Bakurov, his group of companies is referred to under the overall brand 'ExportLes Group'. There is no legal entity of that name, however.

Earthsight has identified 16 different registered Russian companies which are either owned, managed or closely connected to Bakurov.

Click here to read more

Evgeny Bakurov's forest estate in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Dirk Wright for Earthsight

Evgeny Bakurov's forest estate in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Dirk Wright for Earthsight

Lawless logging

Razing forests without anyone noticing used to be easy in Irkutsk province. It is remote, with few roads snaking into the seemingly endless taiga. Until recently, guard posts like the illegal ones Bakurov set up to block access to the forest leases controlled by his companies Vilis and Vertical-B were enough to keep unwanted eyes at bay. Not anymore. The dawn of publicly available court papers and high-quality satellite imagery make it impossible for illegal deforesters to hide their activities.

Drawing on these and other sources as well as our own field investigations, Earthsight established that Bakurov's companies have been systematically flouting environmental and forestry laws for years.

The argument made worldwide is that logging can be made 'sustainable' and not damaging to forests or the wider environment long term, so long as strict rules are followed. In keeping with this, Russia has detailed regulations limiting licensed logging. The volumes allowed to be harvested in a given area each year – the 'annual allowable cut' or AAC – are carefully controlled. The most important areas of forest for the environment or wildlife within a given lease area are placed off limits. Logging methods must follow strict parameters in order to reduce damage to surrounding forests and soils. Loggers must dispose of their waste carefully. They must also take specific actions to promote regrowth: sowing seeds, planting seedlings and leaving some mature seeding trees standing.

Checkpoint illegally blocking access to Vilis LLC logging leases in Irkutsk Region, Russia © Earthsight

Checkpoint illegally blocking access to Vilis LLC logging leases in Irkutsk Region, Russia © Earthsight

Our evidence shows that all five of Bakurov's logging firms – Vilis, Vertical-B, DeepForest, Noviy Les and Bratskwood – have systematically flouted every one of these rules.

Vast tracts of protected woodlands were illegally felled under the false pretext that the trees were diseased or dying. Doubly-protected trees along the banks of rivers and lakes, critical for fish-spawning and erosion control, were clear-cut in their hundreds of thousands. Forests were turned into tinderboxes by the illegal abandonment of huge volumes of logging residues. Riverbanks and shorelines were torn to pieces with heavy machinery. Almost none of the required steps to promote regrowth were carried out.

The overall scene resembles a Russian nesting doll of illegal logging, where dodgy deals unravel and reveal crimes inside crimes inside crimes.

Earthsight asked Alexey Yaroshenko, the head of Greenpeace Russia's forestry department, to confirm our assessment. We asked whether the actions of Evgeny Bakurov's companies broke the law. His reply? "It seems to me that the report gives a completely unambiguous answer to this question: yes."

It is a bitter irony that Bakurov, the same man who decried black lumberjacks enriching themselves by "robbing the country", has presided over the wholesale looting of his region's natural resources.

Earthsight estimates that his companies illegally extracted 2.16 million cubic metres of wood from protected Siberian forests over the last ten years. That is the remains of some 4 million trees, many of them over 150 years old. Piled high, the logs produced from them would rival the Great Pyramid of Giza.

Lead into gold – the illegal deals

The laws his firms have broken are many and varied. But at the heart of this story – and Bakurov's transformation from two-bit nobody into a multimillionaire politician – is one key trick. Evgeny has mastered the art of turning lead into gold.

The process has several stages. First, Bakurov obtains cheaply at auction a license to cut a small number of trees each year (or buys a company which already has one). Then, by nefarious means, he gets the license illegally amended – sometimes multiple times – to allow him to harvest far, far more trees. Even trees within nominally protected and highly sensitive ecological zones are not spared. Once the forest is stripped, he begins the process anew: new company, new forest, new lease, new amendment. By the time the authorities catch up with him, nothing but stumps remain.

Irkutsk territory's arbitration court database lists eleven such cases initiated by regional prosecutors between 2014 and 2020 against the five Bakurov firms. It shows the provincial forest management agency repeatedly bypassed Russia's legally mandated public bidding process (see 'Why the lease changes were illegal') to illegally sign additional agreements to Bakurov's forest lease deals. Judges would later invalidate the amendments in a series of rulings.

Why the lease changes were illegal

Under Russian law, you can't chop down a forest just because a bureaucrat lets you.

Click here to read more

What may sound like a dry legal dispute was, in environmental terms, a disaster. The additional agreements, agreed between September 2012 and July 2018 and covering eight different forest leases, essentially permitted a logging free-for-all across 132,000 hectares of woodland – 85 per cent (111,700 hectares) of which was protected forest.

The deals broke forestry laws by allowing an additional 689,000 cubic metres of timber to be harvested over a short period of time, far more than the roughly 90,000 cubic metres per year allowed originally (of which 40,000 cubic metres was unprofitable 'thinning' of small trees – see table above). Nearly all the added harvest would come from nominally 'protected' forests.

With the illegal additional lease agreements signed, all pretence of responsible forest management went out of the window. The deals permitted a huge expansion of logging, overwhelmingly in the form of clear-cuts and other extensive harvesting said to be needed to save protected trees.

Falsified reports

Because they had breached competition and other laws, the lease amendments would have been illegal even if the felling had been justified. However, they were doubly illegal because the available evidence indicates that the forests concerned were not unhealthy at all.

Details contained in the arbitration court database and inspection reports from the Siberian federal district's forestry department, whose authority includes Irkutsk province, show Bakurov companies DeepForest, Vertical-B and Vilis repeatedly failed to conduct a legally required forest health study before felling trees on the excuse of fighting pests or disease. Under the tight rules that govern sanitary logging in Russia, the country's federal forest agency must first review an expert report known as a "forest pathology act" that recommends trees be removed (see 'How forest pathology acts work'). But, across four lease areas, there was no evidence that any such study had ever taken place.

How forest pathology acts work

If pests or disease take root in a Russian forest, a professional known as a forest pathologist can carry out a tree health check.

Click here to read more

Court files suggest the lack of forest pathology acts was not an oversight. When the arbitration court in 2014 considered a prosecutor's claim to cancel an additional agreement concerning DeepForest, company representatives presented forest pathology acts as supposed proof to justify extensive clear-cutting in the forest lease concerned.

But the acts proved to have been deliberately falsified by Irkutsk's Ust-Udinskiy district forestry chief Yuri Titov, who in May 2021 was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for abuse of office related to the affair. He is serving his sentence in a penal colony.

The Titov affair received attention in Irkutsk. In April 2015, regional prosecutor Igor Melnikov cited the case as evidence of an escalation of sanitary felling acting as a cover for commercial deforestation across the region.

"Bakurov's companies' rapacious logging bore little relation to forest health"

The arbitration court files and Siberian federal district's inspection reports certainly confirm that Bakurov's companies' rapacious logging bore little relation to forest health. According to the documents, there was no basis for the clear-cutting they conducted on sanitary grounds, and any selective felling on the same pretext was either not needed or, in one forest lease, only justified for a tiny share (3.3 per cent) of the additional wood allowed to be harvested there.

In November 2018, the district court in Bratsk banned logging in the lease concerned, after a joint inspection by local prosecutors and an independent forest pathologist found one of Bakurov's companies had cut down "viable stands under the guise of damaged trees".

'People like me don't drown'

Evgeny was not the only local timber baron to discover this trick. But he exploited it like no-one else, and proved more adept at staying ahead of the law.

It didn't take too long for the authorities to cotton on to what was happening with illegal sanitary logging in Irkutsk. But it would take much longer for their efforts to bear fruit. In 2014, the same year that the first of Bakurov's dodgy lease amendments was declared illegal by a court, Irkutsk's regional prosecutor Igor Melnikov publicly acknowledged that protected forests were being "savagely destroyed" through secretive and unnecessary clearances. He alleged that the leadership of the local forest authorities were complicit, including in the deliberate falsification of forest pathological inspection reports. He said he and his colleagues were stamping out the problem, having ripped up more than 100 sanitary logging contracts through suits filed in Irkutsk province's arbitration court and hauled 17 forestry officials before antitrust authorities.

Official data does show sanitary logging fell dramatically across the province between 2012 and 2014, and – following a second wave – fell again from 2018 to August 2020. But on both occasions, one businessman notorious locally for this very crime proved able to buck the trend.

The peak year for sanitary logging in Irkutsk was 2018, at which point Bakurov's firms were responsible for about six per cent of the total amount of such cutting in the province. As the most recent crackdown took hold the following year, the amount of sanitary logging fell by 70 per cent. But Bakurov's firms proved immune. As a result, by 2020 they would end up with a near-monopoly on the pseudo-sanitary logging business. That year, their share would exceed two-thirds.

"When prosecutors defeated one agreement in court, another popped up"

It seemed Evgeny the strongman's claims about being a survivor were no idle boast.

Despite the best efforts of prosecutors to shut down the destruction, nearly all the arbitration suits against Bakurov's firms were filed roughly two to three years after an additional lease agreement was signed. By that time, tens of thousands of trees had already been felled. Meanwhile Evgeny was busy repeating his trick. The process locked prosecutors in a desperate game of whack-a-mole: when they defeated one agreement in court, another popped up.

Lengthy court disputes also bought Bakurov and his cronies time to drive deeper into protected forests before someone stopped them. The regional prosecutors' office applied for an interim ban on logging pending a court decision in only three of the 11 cases, and were successful twice.

The loggers, by comparison, delayed and delayed. They appealed six arbitration decisions, each challenge adding another four months on average to keep cutting trees.

With extraordinary chutzpah, in one case the company's lawyers sought to argue in their defence that there was no point overturning the amendment, because most of the trees had already been cut.

Earthsight's analysis of satellite images shows that illegal deforestation continued in protected forests controlled by Bakurov's companies even after their appeals failed.

It was theft in its purest form.

Both Vertical-B and Vilis continued to cut down trees in protected forests after losing their respective appeals. The well-publicised original ruling against Vertical-B made its actions particularly brazen: local environmental prosecutors had celebrated victory over the company in a press release picked up by local media outlets.

But less than a fortnight after the appeals court ruling, in June 2019, long lines of cut trees began appearing in one of Vertical-B's forestry sites, near Polyanka Bay.

Sentinel satellite images taken every few days revealed fresh clearances sprouting from new logging roads. Within a month, a professional operation had emerged with the site sporting skid trails for dragging logs across the forest floor. Felled trunks could then be hauled down a track connected to the waterway and loaded onto transport boats. Several satellite pictures appear to show barges in the bay or docked at the foot of the track.

Satellite images taken from 3 June 2019 to 1 July 2019 show trees were felled in protected forests within Vertical-B lease 91-21-3, near Polyanka Bay, after the company lost an appeal against the regional arbitration court's ruling. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Satellite images taken from 3 June 2019 to 1 July 2019 show trees were felled in protected forests within Vertical-B lease 91-21-3, near Polyanka Bay, after the company lost an appeal against the regional arbitration court's ruling. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

A similar scene emerged later that summer, when satellite images captured logging at a Vilis forestry site nearly 45 miles away. After Irkutsk's Fourth Arbitration Court of Appeal on 6 August 2019 upheld the ruling against the company, regular rows of stumps appeared beside a skid trail running to the Angara River. Satellite images suggest felling continued until 15 August 2019, when one image captured what appears to be a barge docked at the riverbank.

Satellite images taken from 2 to 15 August 2019 show trees were felled in protected forests within Vilis lease 91-1/9, by the Angara River, after the company lost an appeal against the regional arbitration court's ruling. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Satellite images taken from 2 to 15 August 2019 show trees were felled in protected forests within Vilis lease 91-1/9, by the Angara River, after the company lost an appeal against the regional arbitration court's ruling. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Then, in the winter of that year, there were yet more blatantly illegal clearances, this time in a spawning site along the Ilim River. The third and final offender, DeepForest, continued to cut trees in secret for weeks after the regional forest ministry imposed a logging ban in the area, while the court case involving the lease amendment was pending. Satellite pictures show trees were felled from December 2019, when the ban was issued, until February 2020.

Satellite images taken from December 2019 to February 2020 show trees were felled in DeepForest lease 91-295, along the Ilim River, after Irkutsk Region's forest ministry banned logging during an arbitration dispute over the land. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Satellite images taken from December 2019 to February 2020 show trees were felled in DeepForest lease 91-295, along the Ilim River, after Irkutsk Region's forest ministry banned logging during an arbitration dispute over the land. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Protected forests plundered

It turns out that even the massive windfall from the illegal amendments was not enough to sate Bakurov's appetite for timber. To find out just how badly his activities had affected protected forests within his forest leases, we analysed satellite images going back over a decade.

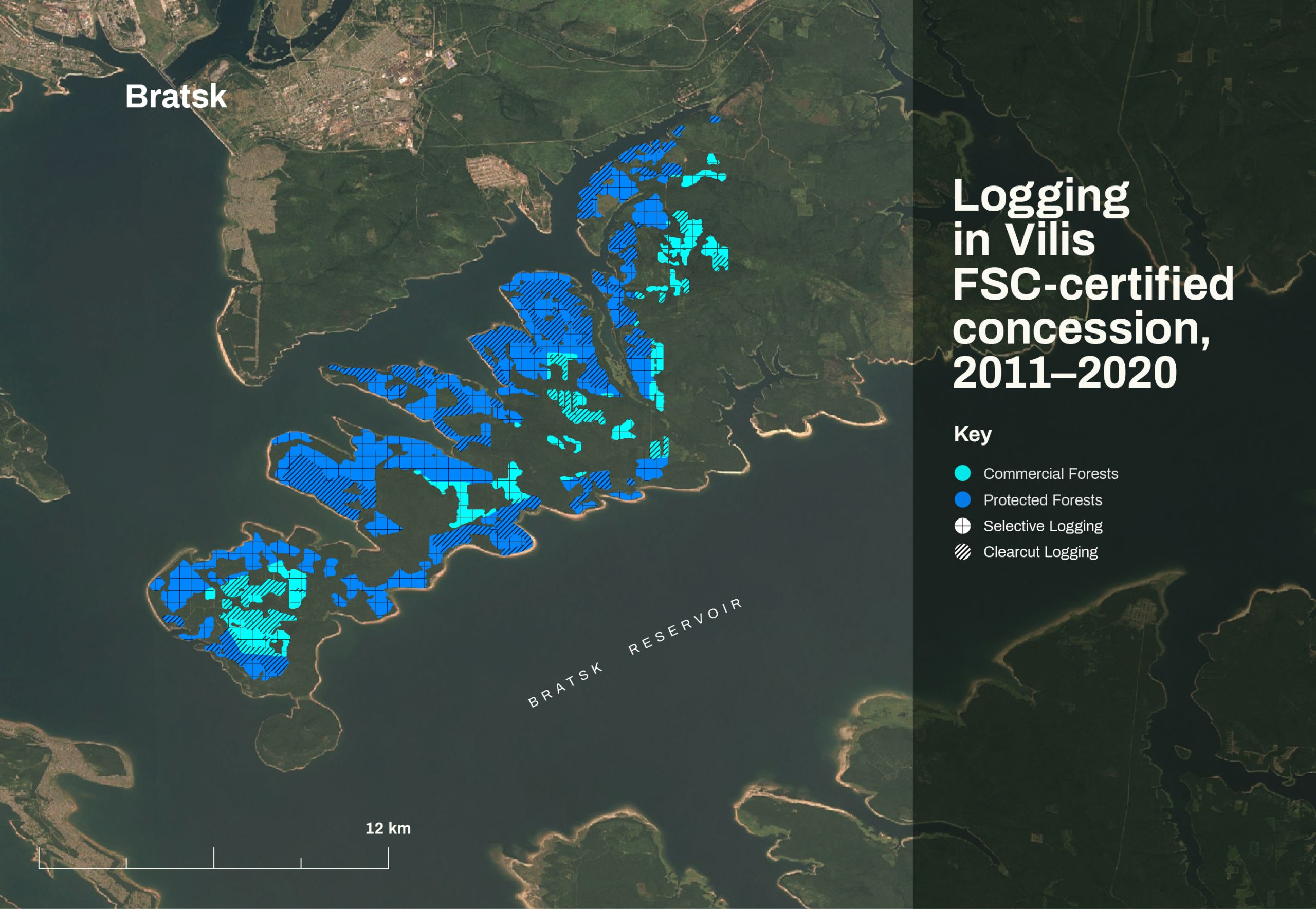

Bakurov's companies control 13 forest leases with a combined area of more than 220,000 hectares, representing an empire bigger than London. Half (51 per cent) of this area – or roughly 112,000 hectares – lies in protected forests spanning shorelines, streams and sources of drinking water.

Using remote-sensing data from satellites, Earthsight tracked deforestation in 10 of the 13 forest leases over a period longer than a decade. The study area, more than 200,000 hectares, accounted for most of the land under Bakurov's control, and includes all eight leases where illegal amendments were made.

We discovered that 14,600 hectares of protected forest controlled by his five firms were felled from 2009 to August 2020 – 79 per cent of the total area logged over the period. More than half of this logging in protected forest was the most devastating and environmentally damaging kind – clear cuts. As the area under Bakurov's control grew, so did the area of nominally protected forest being damaged and destroyed, peaking in 2019.

Based on the area logged or deforested and the intensity of logging, Earthsight estimates that Bakurov's five firms cut 2.16 million cubic metres of wood in protected forests from January 2011 to August 2020. That is more than three times the volume allowed by the illegal lease amendments. It is wood worth almost a quarter of a billion US dollars.

The only way any such logging could have been even remotely legal was if it were being carried out for reasons of forest ill-health. There is a fair chance it was just blatant criminality. According to Greenpeace, felling in excess of licensed harvests is even more common in Russia than 'pseudo-sanitary' felling.

It is also possible that additional permissions for such harvesting were given, which neither we – nor, it would seem, local prosecutors – are aware of. But even if that were the case, what odds would you get that the forest concerned was truly sick?

We can be more certain about the illegality of much of this logging, however, because the satellite images show that it took place in forests close to the shores of rivers and the Bratsk reservoir. Recognising their crucial ecological value as spawning, feeding and wintering grounds for fish and other aquatic life, as well as for erosion and flood control, legislation prohibits felling in zones within 200 metres of such shorelines.

Satellite images taken from 2013 to 2020 show logging in Vilis forest lease 7-09 near the shores of rivers and the Bratsk reservoir. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Satellite images taken from 2013 to 2020 show logging in Vilis forest lease 7-09 near the shores of rivers and the Bratsk reservoir. Satellite imagery: European Space Agency (ESA) Copernicus Sentinel / via Sentinel Hub

Even if the forest is diseased, only selective felling is permitted. Yet the satellite images reveal dozens of locations within the Bakurov forest estate where clear-cuts took place in such areas. These were not small offences. One such illegal clearcut covered an area larger than 50 football pitches and extended along the coast for three kilometres. They were also blatant. In some cases, a thin 'screen' of trees was left close to the bank, perhaps to hide the illegal felling from sight. But in many places, the clearances went right down to the shoreline.

Logging in protected and commercial forests within one of Bakurov's FSC-certified Vilis concessions, lease 7-09, near Bratsk, Russian Siberia, 2011-2020 © Dirk Wright for Earthsight

Logging in protected and commercial forests within one of Bakurov's FSC-certified Vilis concessions, lease 7-09, near Bratsk, Russian Siberia, 2011-2020 © Dirk Wright for Earthsight

Zyaba bay, July 2017

Zyaba bay, May 2020

Soldatskiy bay, September 2018

Soldatskiy bay, May 2020

One reason they were clearing forest along these fragile shorelines illegally was as a cheap means of transporting their logs out of the forest. Rather than transport the logs by the established logging roads as required by law, which was difficult and expensive, particularly during the muddy summer months, Bakurov's firms made systematic use of the neighbouring rivers and reservoir instead. Miles of precious shoreline was ripped apart by heavy machinery, as tens of thousands of logs were violently dragged across it to waiting barges.

Bakurov's firms were caught red-handed in such illegality multiple times. On three separate occasions during 2018-2019, Bratsk environmental prosecutors took logging firms operating under contract in Bakurov's leases to court for such breaches. The records show that field inspections by the authorities revealed numerous cases where shorelines had been torn up, littered with logging debris and polluted with engine oil.

Satellite images taken from 2016 to 2019 show a protected shoreline within Vilis forest lease 7-09 used to store logs and load them onto barges at Zmeiniy Bay, in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. Satellite imagery: Maxar Technologies / CNES / Airbus / Google Earth

Satellite images taken from 2016 to 2019 show a protected shoreline within Vilis forest lease 7-09 used to store logs and load them onto barges at Zmeiniy Bay, in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. Satellite imagery: Maxar Technologies / CNES / Airbus / Google Earth

Wasteland

Squinting at satellite photos taken from hundreds of miles above the earth wasn't enough. In September 2020 Earthsight visited logging sites within protected forests controlled by Bakurov's companies to witness the destruction for ourselves. We travelled to six sites in Irkutsk's Bratsk and Ust-Udinskiy districts, unearthing yet more violations of environmental and logging laws.

We saw no signs of sickness or pests on stumps that survived sanitary clear-cutting. Nor were neighbouring forest stands visibly weak, dead or dying. In fact, valuable conifers had been chopped down while cheaper species were left untouched. Dead trees which should be priorities for felling and removal during real sanitary logging had also been left standing.

Log loading bay in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Earthsight

Log loading bay in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Earthsight

Visiting sites of illegal deforestation along the shores of Bratsk reservoir, we found them strewn with equipment, machinery and vehicles. Vehicle tracks and log piles littered the scene. Along the reservoir, man-made embankments served as temporary berths for loading wood onto barges and the loggers had even set up a parking lot. In one illegal clearance almost a kilometre long along the shore of the lake, we found it pockmarked along its length with channels cutting up to three metres deep into the fragile soil down which logs had been dragged.

In logging site after logging site, we found the ground littered with dead logging residues such as discarded branches and destroyed undergrowth. Illegal abandonment of such residues in the manner seen leads to much greater fire risk. If the forest concerned had indeed been infested with pests and disease as claimed, such illegal behaviour by loggers also promotes further spread and undermines the very purpose of the harvesting.

Logging site in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Earthsight

Logging site in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia © Earthsight

Earthsight's field visits also confirm that the companies Bakurov controls are systematically failing in their legal obligations to help forests grow back once loggers have left. Such 'reforestation' activities are commonly cited by Bakurov publicly as evidence that his activities don't harm the forest or wildlife in the long-term. Though sometimes seen as relative technicalities, they are a crucial part of the wider logic which the forestry sector uses to justify logging and paint it as environmentally friendly.

Yet arbitration court files contain evidence of his firms skipping some of their required reforestation duties, trying to avoid them and, in some cases, falsely stating that they had performed them. Bakurov's firms have been repeatedly fined as a result. In one case in 2017, to the tune of 5 million roubles ($84,000). Our field checks suggest that these cases are the tip of the iceberg, with failures of this kind standard practice in forests under Bakurov's control.

New friends, new tricks

One likely reason that Bakurov was able to stay ahead of the authorities longer is his powerful political and government connections. But by 2019, his allies were starting to suffer the consequences of colluding with businessmen such as him, and his position was beginning to look increasingly precarious.

First came the downfall of the Irkutsk forest minister Sergey Sheverda in early June 2019, for his role in illegally approving sanitary felling of healthy forest in a nature reserve. Prominent regional political observers immediately and publicly raised Bakurov's name in relation to the case, and local press reports also alleged the involvement of his firms, though Earthsight could find no evidence to support this.

Less than a month later, his boss was also in trouble, again with a forest-related connection. Floods hit Irkutsk in late June and early July, displacing tens of thousands, killing at least 18 people and hitting the headlines nationwide. Local press reports alleged that the illegal logging of coastal protection zones – including by Bakurov – had contributed to the devastation. Greenpeace Russia's forest chief agreed that suspect 'pseudo-sanitary' felling had likely contributed.

The response brought the region to the attention of the Kremlin. Irkutsk's top official, Governor Sergey Levchenko – a key Bakurov ally – came under growing criticism for his poor response to the disaster, and in December 2019 was finally sacked.

Sergey Levchenko. Photo: Office of the Russian President

Sergey Levchenko. Photo: Office of the Russian President

With his key allies out of office and illegal sanitary logging in the state garnering unprecedented attention among the public and even as far as Moscow, the net began closing in on Evgeny Bakurov. The flow of dodgy lease amendments stopped and within a year of the floods and Sheverda's downfall logging was finally brought to a halt by the courts in seven of Bakurov's eight remaining illegal amendments. The last one was finally halted, two years too late, in February 2021. Earthsight's satellite eye-in-the-sky confirmed that the party appeared to be over.

A lesser man might have taken defeat gracefully. After all, though officials had been arrested, sacked or jailed, Bakurov and his companies had pocketed millions and suffered little more than the odd minor fine. He could have rested on his laurels, sat back and enjoyed his new-found wealth. But that would be to underestimate Evgeny Bakurov. Instead, he was quick to cultivate new friends and invent new tricks.

When his long-term ally Levchenko was sacked by Putin in December 2019, Bakurov moved quickly to befriend his replacement. When acting Governor Igor Kobzev looked to confirm his position in the legislative elections of September 2020, timber companies owned or closely linked to Bakurov were among the most generous contributors to his campaign. Records show they supplied 12 million roubles ($160,000), 10 per cent of the total funds raised.

As well as a new ally, Bakurov also has a new trick. With the sanitary logging scam providing an increasingly difficult route to riches, Russia's illegal timber barons have hit on a new scheme: Priority Investment Projects (PIPs).

Earthsight report Taiga King © Earthsight

Earthsight report Taiga King © Earthsight

The PIP scheme was designed to promote downstream processing in the Russian wood industry but has evolved into a scam which logging companies illegally abuse to gain cheap access to forests and benefit from state subsidies. One such project was at the heart of Russia's largest illegal timber scandal this century, which occurred in Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East. As Earthsight documented in an explosive report, in 2019 Russia's domestic spy agency blew the lid on the case, arresting the timber baron involved. Prosecutors alleged that his company wood processing facility was a sham, used to cover the illegal harvesting of some 600,000 cubic metres of logs. The man in charge of Khabarovsk's forest industry during the height of the scam was found guilty of abuse of office in 2020 as a result. The timber baron behind the scam also admitted paying bribes to a federal official in Moscow.

In response to the scandal, Russian president Vladimir Putin ordered his government to strengthen state oversight of priority projects. But with key decisions remaining in the gift of local officials, the opportunity for graft remained.

In December 2020, two months after his successful election, one such official, Irkutsk governor Kobzev, announced three new forest-related Priority Investment Projects for his region. One of those projects, it later emerged, has been given to Bakurov-owned timber firm Angri LLC, one of those generous political donors. The project will bring with it the rights to cut 422,300 cubic metres of timber – or approximately 700,000 trees – each and every year.

3. Connecting

to the world

Not so remote

The dense coniferous forests of Irkutsk are about as remote as it gets. To the south stretch the vast empty deserts of Mongolia. To the north, an unbroken expanse of wilderness touches the frozen Arctic. From Bratsk, the nearest open water port is more than 1,600 miles away; Moscow another 800 miles, across a mountain range and five time zones.

It is not a place you would expect to be well-connected to the outside world. And on the face of it, for Bakurov's little timber empire, this would appear to be true. His companies process few of the trees they cut. Most are sold to local wood product manufacturers. The exports he does have are to nearby China.

"The first clue came from Bakurov himself"

Yet ours is a globalised world, and the tentacles of big business reach even its remotest corners. As it turns out, there are threads connecting Bakurov's business to every part of the planet – and to one of its biggest corporate names.

The first big clue to how to trace these threads came from Bakurov himself. A promotional video for his firms published on YouTube in 2016 shows him brag of supplying none other than the largest wood product retailer in the world: Ikea. He said the multibillion-dollar brand had initiated the relationship some years earlier, and claimed the Swedish giant was particularly pleased with his ability to deliver the goods. "After seven years of Ikea's work in Russia with logging companies," Bakurov claimed the retailer had told him, "we chose your company because you send logs faster than we can transfer the money."

Going undercover

In that same promo film, Bakurov claimed to supply wood to factories near the Chinese port city of Qingdao, whose main customer is Ikea. While initially the wood ending up with Ikea was leaving Russia as logs, he also claimed to have persuaded the Swedish firm to support the setting up of a sawmill in Russia to do primary processing there.

But it remained uncertain which Ikea products were concerned, and which Chinese factories were making them. It was also possible that the business relationship had since broken down, perhaps because of the court cases and media reports revealing wrongdoing by his firms. Or perhaps Bakurov was simply lying.

Earthsight investigators went undercover early this year to find out. We tried to contact the timber baron. Though he proved elusive – too busy with political campaigning to talk – we were able to speak to his deputy, Vadim Kovalevsky. Kovalevsky confirmed that Bakurov's group continued to supply Ikea, including via a local processing company called Uspekh – Russian for "success".

Uspekh wood processing factory in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. Satellite image: Maxar Technologies / Google Earth

Uspekh wood processing factory in Irkutsk Oblast, Russia. Satellite image: Maxar Technologies / Google Earth

"Yes," said Bakurov's right-hand man, "we [still] have buyers who buy wood from us and then sell it in the form of finished products to Ikea."

Data from the Russian government's wood tracking system, LesEGAIS, confirmed Bakurov firm Kapel (which conducts the logging in his leases, including Vilis) as the largest supplier of raw materials to Uspekh, which is itself located right next door to Bakurov's own processing site in a town close to Bratsk. Uspekh turns the wood into small, planed pine staves, which are glued together to make boards. During the period from January 2020 to March 2021, nearly half (49 per cent) of Uspekh's raw materials came from Bakurov's forest lease-holding companies. And almost all (93 per cent) of Uspekh's supplies from companies certified by global green auditors the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) – the only wood that Ikea accepts – came from Bakurov.

While undercover, and after an introduction from Kovalevsky, Earthsight spoke to Uspekh’s director, Anna Prelovskaya. She confirmed her company sourced from Bakurov's group and said that they had been supplying wood used in making Ikea furniture for over six years.

Prevlovskaya added that Ikea represents a significant share of the company's total turnover, which varied from 50 per cent to 70 per cent, depending on the season.

Logo of Indonesian furniture manufacturer and Ikea supplier PT Karya Sutarindo. Source: Earthsight

Logo of Indonesian furniture manufacturer and Ikea supplier PT Karya Sutarindo. Source: Earthsight

She went on to say that the Ikea manufacturers her company supplies include one based in Southeast Asia, but would not provide its name. The director also wouldn't say which specific Ikea products used her company's wood.

Fortunately, we had other means of finding this out. Customs records obtained by Earthsight show Uspekh regularly ships large volumes of pine staves and boards to an Indonesian firm called PT Karya Sutarindo. Its factory is in the town of Sukorejo, part of the furniture manufacturing hub surrounding the port of Surabaya, East Java.

At a facility nestled at the base of the active 11,000-foot volcano Mount Arjuno, workers clad in matching light-blue shirts – most of them women – have churned out furniture for one of the world's best-known brands for more than 15 years, we learnt.

Though nominally independent like most Ikea suppliers, Sutarindo depends almost entirely on the Swedish furniture giant for its business. Ikea was responsible for 96 per cent of the company's sales in 2019.

Just one of the ways illegal wood from Bakurov's Vilis lease made its way into Ikea products © Matt Hall for Earthsight

Just one of the ways illegal wood from Bakurov's Vilis lease made its way into Ikea products © Matt Hall for Earthsight

Child's play

Sutarindo's main business is in kids' furniture – and it is a booming one.

The global market for children's furniture in 2018 was worth $29.4 billion, and is expected to grow by almost 5 per cent annually in the coming years. More than 60 per cent of this furniture is made of wood. The continued success of the children's furniture market has seen big brands signing licensing deals with top fashion designers and celebrities like Hollywood actress Drew Barrymore. The pandemic accelerated this growth, closing schools during national lockdowns and forcing parents to set up home classrooms. Industry experts note that buyers of children's furniture are also more likely to be concerned about sustainability.

Ikea's children's range accounts for between 6 and 8 per cent of its overall business in its mature markets, though this proportion can be much higher in emerging ones like India. Figures contained in Ikea's annual report suggest the company's total sales of kids' products were more than €3.2bn last year.

Though it is cheap, the brand's trendy designs draw customers from a broad range of backgrounds. Even the third in line for the British throne, seven-year-old Prince George, has Ikea furniture in his bedroom. During a tour of an Ikea store in Stockholm in 2018, his parents, the Duke and Duchess of Cambridge, better known as William and Kate, revealed they had bought such furniture for his sister too.

Many of the items in this Ikea display are made by the Indonesian firm which is using Bakurov's wood © Earthsight

Many of the items in this Ikea display are made by the Indonesian firm which is using Bakurov's wood © Earthsight

Last year, Sutarindo supplied more than 2.2 million items of children's furniture to Ikea with a retail value of $60 million, Indonesian records obtained by Earthsight show. That's equivalent to 2 per cent of Ikea's total revenues that year. The goods included best-selling products like the discount Latt table and chair set and most of the items in the Sundvik children's range – chairs, tables, beds and wardrobes, among others.

The records also reveal the Indonesian company ships to Ikea stores in countries worldwide, including the United States, China, Russia, Japan, Germany, France, Italy, the United Kingdom, Spain, Belgium and Canada. Of these sales, 45 per cent were destined for the European Union, and another fifth for the US.

Pine, the main material in these products, does not grow in Indonesia. Sutarindo must instead import it from overseas.

Digging further, Earthsight discovered that the Russian processing company closely linked to Bakurov, Uspekh, is one of Sutarindo's largest suppliers of pine. Nearly a quarter, by value, of the pine the Indonesian firm imports to make Ikea furniture comes from Uspekh, which sends it about 200 tonnes of pine staves each month. Packed into cargo containers, the goods trundle along the Trans-Siberian Railway to Vladivostok in the Russian Far East, from where they are shipped.

Roughly 1,700 Russian trees, nearly all of them supplied by Bakurov and many illegally logged, flood into this Indonesian Ikea factory each month. By a conservative estimate, one Ikea product containing this wood is sold somewhere on earth every two minutes.

Responding to our allegations just prior to publication, PT Karya Sutarindo told Earthsight that it does not use wood "from the region you speculated" (i.e. Russia) for two specific Ikea products (the Latt table and Mala easel), but pointedly did not deny using Russian wood from Bakurov's company for other products which they supply to the Swedish giant. They went on to say that they were investigating our allegations and "continue to insist on procuring legally sourced wood".

Flisat doll's house and wall shelf, one of the products made by Indonesian furniture maker PT Karya Sutarindo, on sale in an Ikea store in the UK, May 2021 © Earthsight

Flisat doll's house and wall shelf, one of the products made by Indonesian furniture maker PT Karya Sutarindo, on sale in an Ikea store in the UK, May 2021 © Earthsight

All roads lead to Ikea

While the clearest route by which Bakurov's dirty wood reaches Ikea stores is via the children's furniture made by PT Karya Sutarindo in Indonesia, it is not the only one.

Bakurov's firms continue to ship large volumes of logs and lumber certified by the Forest Stewardship Council to China, home to some of Ikea's largest suppliers. Those suppliers remain heavily dependent on the steady flow of FSC certified wood from Russia. And when he spoke to us, Bakurov's deputy Vadim Kovalevsky said he believed this wood was still being used to make Ikea goods in China (although he didn't know the names of the factories doing this). During discussions with undercover Earthsight investigators, Uspekh's director also claimed to have recently sold wood to an Ikea supplier in the country but refused to give its name.

Bakurov has previously mentioned Ikea suppliers in the Qingdao area of the province of Shandong using his wood. If so, this was likely done through a handful of large Ikea suppliers clustered in the small district of Zhucheng, well-known locally as the 'home of woodenware'. At least five big Ikea suppliers crammed cheek-by-jowl around one village, Shiqiaozi, together churn out upwards of 10 million items of furniture and other wood products for Ikea every year. Like their Indonesian counterpart, they are technically independent but utterly reliant on the Swedish cash cow.

Wang Shiliang, export manager of one of the largest of these firms, a company called Song Yuan, says the entirety of its $57 million in annual sales goes to the furniture giant. Ikea places the factories under huge pressure to deliver rapidly increasing volumes at bargain prices. Executives confess that Ikea's power exerts a stranglehold over them, forcing them to be obedient to its demands and cut costs. Otherwise, they worry, Ikea could easily drop them, leading to inevitable bankruptcy.

"Suppliers remain heavily dependent on the steady flow of FSC certified wood from Russia"

Wang and his boss explained to a Chinese journalist in 2019 that the biggest problem they face in delivering on Ikea's demands is their supply of raw materials from Russia. The imports account for more than half of the cost of the finished products they make, and with the difficulty of transporting logs and lumber from Siberia and the Russian Far East shortages of supplies are common. To get around the issues, many of these Ikea suppliers have made their own investments in Russia, including in Irkutsk province. Song Yuan alone has invested $30 million in the country and claims to control 260,000 hectares of forest.

These Chinese firms sell a wide range of products made from Russian wood – mostly pine, but also birch – to Ikea, including step stools, wine racks and wooden bowls. Many likely contain Bakurov's tainted timber.

A third route into Ikea runs through Russia itself. Both the director of Uspekh and Bakurov's deputy claimed to directly supply or have supplied Ikea's own factories in the country. Uspekh's director said her firm sold wood to them until early last year, when Covid-19 interrupted business.

Ikea has three sawmills in Russia, churning out furniture and furniture parts. The largest, at Novgorod, uses only chipboard, but its mill at Vyatka uses solid pine to make popular items such as Neiden bedframes and Lerhamn tables. Records show the products are shipped to countries including the USA, UK, Germany and France.

Tainted trade

Ikea is by no means the only buyer of Bakurov's dodgy wood in Europe or the United States. Sutarindo, we learned, also ships children's furniture to two of Ikea's biggest competitors in the United States. Though in response to our finding the Indonesian company insisted that none of these exports were made with their Russian pine, if true it appears this was more by chance than by design.

And while Bakurov's companies don't ship to Europe directly, they supply several large local mills which do. Trawling through the data, we established that in total, European firms import at least €170 million a year in wood products tainted with illegal logs from Bakurov's operations. His suspect goods contaminate a large proportion – perhaps even a majority – of eastern Russia's exports to the continent.

4. Laundering machine

Tip of the iceberg

Earthsight's findings represent just the tip of the iceberg with respect to the presence of illegal Russian wood in both Europe and Ikea.

Ikea's consumption of Russian wood has skyrocketed in recent years. The firm used 1.9 million cubic metres of Russian logs in 2019, almost double that of five years earlier. The staggering volume represents at least a million felled trees.

Russia is Ikea's second-largest source of wood after Poland. Its forests represent a growing share of the company's supplies with stocks from elsewhere already maxed out. In 2014, 6.5 per cent of Ikea's wood came from Russia. By 2019 the proportion had risen to 9 per cent.

Ikea even has its own forests in Russia. But these supply only 7 per cent of its Russian wood needs. The rest comes from a raft of third-party suppliers, of whom Bakurov is just one.

FSC logo. Source: FSC

FSC logo. Source: FSC

To ensure this wood is legitimate, Ikea relies heavily on the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC) certification scheme. Founded in the early 1990s by a group of environmental charities and progressive timber firms, FSC has grown into a behemoth. Its auditors visit and check 2.3 million square kilometres of forest worldwide each year (an area one quarter the size of the United States), supposedly ensuring that logging there is both legal and kind to people and wildlife. FSC's cuddly green tree-tick logo adorns thousands of everyday products, from tissue paper to furniture, books and even clothes made from viscose pulp.

Though it was originally meant to be a tool for environmentally conscientious consumers to ensure that they weren't contributing to global deforestation, FSC’s label has increasingly become a must-have for companies wanting to stay within the law or sell to governments and other big buyers. Some forest countries have made certification from FSC or its equivalent compulsory for loggers and timber traders, while many of the biggest international markets for wood, including the US, EU, UK, Australia and Japan, have passed legislation which makes it hard to import or sell the stuff without it.

Brothers in arms

The biggest driver of FSC's growth, however, has been Ikea. The Swedish furniture retailer was among the organisation's founders and is by far the largest consumer of wood carrying its label. Ikea committed a decade ago to source all its fresh wood from FSC-certified forests, a target it achieved last year. The brand almost failed to meet its goal – and would have done so were it not for Russia.

Almost entirely due to demand from Ikea, the area of FSC-certified forest in Russia has grown dramatically. With growth elsewhere flatlining, business from Russia has been the principal driver behind FSC's aggressive worldwide expansion.

In the five years to 2019, Russia represented 62 per cent of net global growth in FSC's certified forest area. Most of the remaining growth came from neighbouring Ukraine and Belarus, which are plagued by similar problems. Ikea's demand for wood from Russia has risen in lockstep with the area of FSC forest in the country.

Ikea's growing Russian wood consumption has driven a rapid increase in FSC-certified forest in the country.

An area of Russian forest the size of France is now FSC certified – equivalent to 14 per cent of its production forest (woodland in which logging is allowed).

Of this area, 30 per cent is in Siberia or the Russian Far East. And the largest expanse of certified forest within this region by far? Irkutsk province. Woodlands under the FSC banner in the remote territory include parts of the Bakurov empire where Earthsight documented rampant lawbreaking.

Ikea's support for FSC in Russia should have been a good thing. The vast country was well known for poor forest governance, with illegal and unsustainable logging the norm. By bringing in third-party auditors and ending the reliance on governments to police logging, FSC was supposed to improve things. In some ways it has. But fundamental flaws in how it works have led it astray.

Alexey Yaroshenko from Greenpeace Russia is well aware of FSC's flaws. He told Earthsight that voluntary forest certification schemes are unable to protect precious forests or guarantee that accredited wood products are made from legal and sustainable materials.

"We appreciate the striving of our colleagues from the FSC to make Russian forestry and forest exploitation more responsible and legal," he added, "but we understand that so far this has not been very successful."

FSC's failures would prove costly in the Bakurov saga, particularly for Ikea.

Elephant in the room

When auditors visit a logging company to assess its activities against the FSC criteria, they are required to publish a summary of their findings. This transparency is intended to ensure that anyone can see what the auditors found and how they came to their decision. Often, the most revealing details of what is really happening in a forest come not in the form of what these reports say, but what they miss out.

Over time, such reports can run into hundreds of pages. With language largely impenetrable to all but a select few, they include microscopic details on trivial matters. Yet all too often they also manage to omit – or perhaps deliberately obscure – hugely important facts. In one forest in Ukraine, for example, audit reports obsessed over the type of trousers loggers were wearing – while neglecting to mention the rampant lawbreaking the environmental police had exposed there.

The proverbial elephant in the room in the Bakurov case was far larger. This is because, shockingly, some two-fifths of the forests where Bakurov's companies have been engaged in wanton destruction in recent years have had the FSC imprimatur that whole time. After more than 10 years of checks, the published reports run to a combined 234 pages. The auditors found time to record how many ambulances the local hospital has, along with a single case of a fuel storage tank being put in the wrong place. But, somehow, they failed to notice an illegal timber grab of quite startling dimensions happening right in front of their eyes.

"Auditors failed to notice an illegal timber grab of quite startling dimensions"

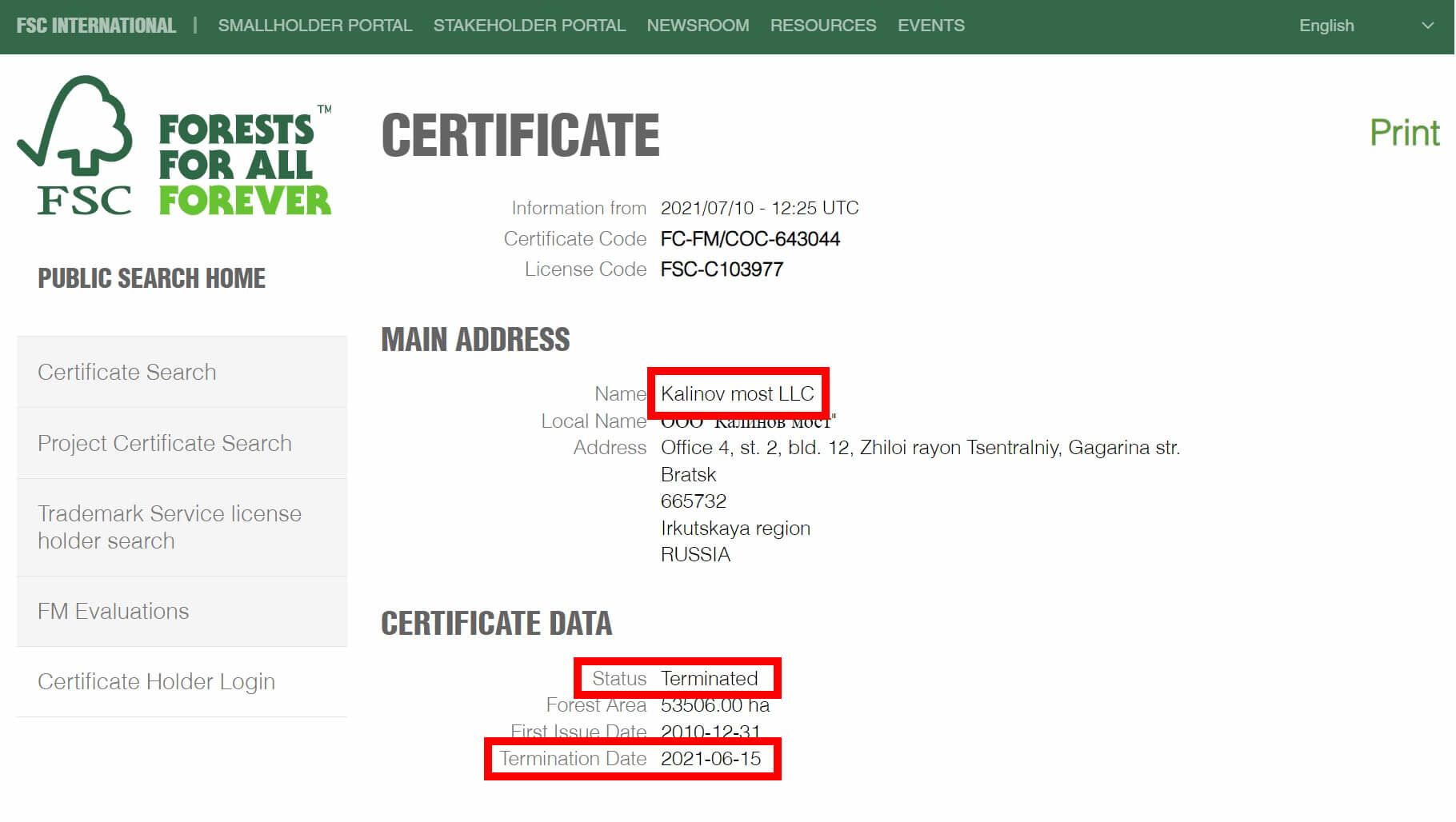

The logging in 95,000 hectares of forest leased to Bakurov's Vilis LLC was first certified in December 2010 by Forest Certification LLC, Russia's home-grown FSC-accredited auditing firm. Since then the company's auditors have been back no fewer than 13 times. What they missed confounds belief.

All the illegal acts described in Chapter 2: 'The heist' were detected by Russian authorities or Earthsight in Bakurov's FSC-certified Vilis concession, as well as in other Bakurov forest leases. The charge sheet is stark: court decisions have ruled that amendments to three of the five FSC-certified Vilis leases were illegal; field evidence confirms the unjustified and illegal nature of this sanitary logging by showing that the forest concerned was healthy; in one of the FSC-certified leases, satellite images show illegal logging continued even after the courts invalidated the lease amendment concerned; the illegal sanitary clearcuts within the Vilis concessions included some of the largest areas within the wider Bakurov estate in protective zones along the edges of lakes and rivers, areas especially important for the spawning of fish and prevention of erosion and pollution of water sources; in 2019, 86 per cent of all timber cut within the Vilis concession certified by FSC came from illegal sanitary harvesting in protected forests; and more than 40 per cent of trees illegally harvested in protected forests across the Bakurov empire over the last decade were cut in Vilis's certified land leases.

A large proportion of the illegal felling in nominally 'protected' forests within Bakurov's forests took place in his FSC-certified concession

In short: there have been publicly available indications of wrongdoing by Bakurov's companies, including within the FSC-certified Vilis concession, for years. FSC auditors reported none of this information. Instead, the lease amendments which vastly increased the scale of felling in the concession went unremarked on. Auditors also made no mention of the controversy regarding the legality of these lease amendments, despite the allegations by local prosecutors having been a matter of public record since September 2014 for Bakurov's wider group and October 2018 for Vilis in particular, and court decisions relating to these allegations being a matter of public record since December 2014 for Bakurov's wider group and in April 2019 for Vilis in particular.

The scandal regarding this illegal sanitary logging by Bakurov's companies, including Vilis, has also been repeatedly mentioned in the local press since 2015. Yet once again FSC auditors did not mention this in their annual inspection reports.

Nothing to see here

So how did auditors seem to miss such obvious illegal logging and environmental crimes? Were they asleep, hoodwinked or simply incompetent? At best, the case indicates wilful blindness on their part.

Despite glaring omissions, the summary reports show that the auditors weren't entirely in the dark. The documents suggest auditors knew that the allowable cut in the Vilis leases had dramatically increased, since they dutifully reported the revised numbers. But they didn't note or comment on the changes. The reports also reveal that auditors were aware as early as 2010 that Vilis was conducting sanitary logging in protected forests. And while auditors did not need to visit each separate part of the company's FSC-certified land leases on an inspection, the reports claim that auditors paid multiple visits to the two leases where we know widespread sanitary felling was happening in protected forests, at the time it was happening. In every report, the auditors claim that their field checks included ones relating to the justifiability of sanitary felling. They also claim to have included visits to the boundaries of protected forest zones along the banks of water sources.

"Auditors weren't entirely in the dark"

It certainly seems implausible that forestry professionals could be ignorant of Russia's problem of illegal sanitary logging, or the scandal surrounding it in Irkutsk, the country's biggest timber producing province. The matter was well known to all those engaged in the forest sector, be they in the remotest taiga or Moscow. It is also hard to see how the systematic breaches of regulations during harvesting, as detected by Earthsight's research, do not appear to have been spotted during the annual field checks that supposedly took place.

However, while individual failures by the Russian company doing the audits likely played a part, the certification scheme's flawed systems and procedures were at least as important in explaining this fiasco. Earthsight and others have highlighted such structural defects in previous reports relating to FSC certification in other countries, but still they remain.

Blinkers on

The problems started the moment the certification was first approved.

To avoid its brand being used to mask, or greenwash, environmental abuses and wrongdoing, FSC requires logging companies to declare all of the forests they control, not just the land they are looking to have certified. Uncertified forests are not subject to the full list of FSC's checks, but auditors are expected to carry out some basic due diligence on logging within them like ensuring it meets minimum legal standards.

Importantly, however, the rules don't require the auditors to check whether the company being certified has been honest in its declaration. They also leave some room for interpretation over which of its affiliated corporate entities need to be declared. In this case, Bakurov's logging companies DeepForest, Vertical-B and Noviy Les were never declared in FSC public summaries for Vilis despite all four firms being owned by the same man. As a result, auditors were under no obligation to monitor whether they were engaged in criminal activity, despite plentiful clues that they formed part of a larger whole.

It was for this reason that auditors did not notice – or could ignore – the scandals involving Bakurov's uncertified firms long before they spread to Vilis. One of the most damning examples of confirmed illegal, unjustified sanitary felling in protected forests considered in this report involved Bakurov outfit DeepForest, in which a forest official was jailed for falsifying documents claiming trees in one of the company's forest lease were diseased. Local press reports also alleged the involvement of Bakurov's wider group with the illegal sanitary logging in Tukolon Wildlife Refuge which resulted in the arrest of the provincial forest minister (Earthsight was not able to substantiate these claims). The FSC reports mention none of this.

Timber laundering

The lawbreaking taking place in the parts of Evgeny Bakurov's forest estate that are not certified are potentially more important to this story than they might first appear. And again, the fault lies with FSC's core systems.

Ensuring illegal wood is not laundered through certified supply chains is a crucial function for forest certification schemes. Unfortunately, a series of scandals shows FSC is failing to stem the flow of dirty timber despite a growing arsenal of technologies now available to detect it.

"The fault lies with FSC's core systems"