'Everything can be obtained here'

Trafficking indigenous land in the Paraguayan Chaco

The forests of the Paraguayan Chaco are home to the only indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation anywhere in the Americas outside the Amazon rainforest, the Ayoreo Totobiegosode. But they’re also disappearing faster than any other forests on earth.

This destruction is driven by cattle ranching firms to meet international demand for beef and leather, with supply chains implicating some of Europe’s biggest leather and automotive firms, as detailed in Earthsight’s investigation Grand Theft Chaco.

Earthsight's investigation, Grand Theft Chaco: The luxury cars made with leather from the stolen lands of an uncontacted tribe, released in September 2020. © Earthsight

Earthsight's investigation, Grand Theft Chaco: The luxury cars made with leather from the stolen lands of an uncontacted tribe, released in September 2020. © Earthsight

Through the past three decades, settled Ayoreo Totobiegosode activists have fought to defend their ancestral territory. Their efforts compelled the creation of a 5500 square kilometre tract of protected forest, known by its Spanish acronym PNCAT.

Recognised by the Paraguayan authorities in 2001, PNCAT is home to semi-nomadic Totobiegosode groups, living in voluntary isolation, who rely on the forests for their material, cultural and spiritual survival. Today, the Totobiegosode possess property titles to more than 124,000 hectares of PNCAT land. Developing any of the rest of the territory is prohibited by both Paraguayan law and protective measures issued by the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights (IACHR).

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades © Survival InternationalGAT

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades © Survival InternationalGAT

However, despite these hard-won protections, Earthsight has discovered that land within PNCAT is still being offered to international buyers, with the suggestion that they can clear forest and extend ranching operations deeper into Totobiegosode territory.

In February 2020, undercover Earthsight investigators met with a land-broking firm named GD Agronegocios.

Talking over coffee in a shopping mall in Paraguay’s capital, Asuncion, company representatives offered us not one, but two properties that lie within the Totobiegosode territory. One of the properties overlaps land officially titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode in the Paraguayan land registry.

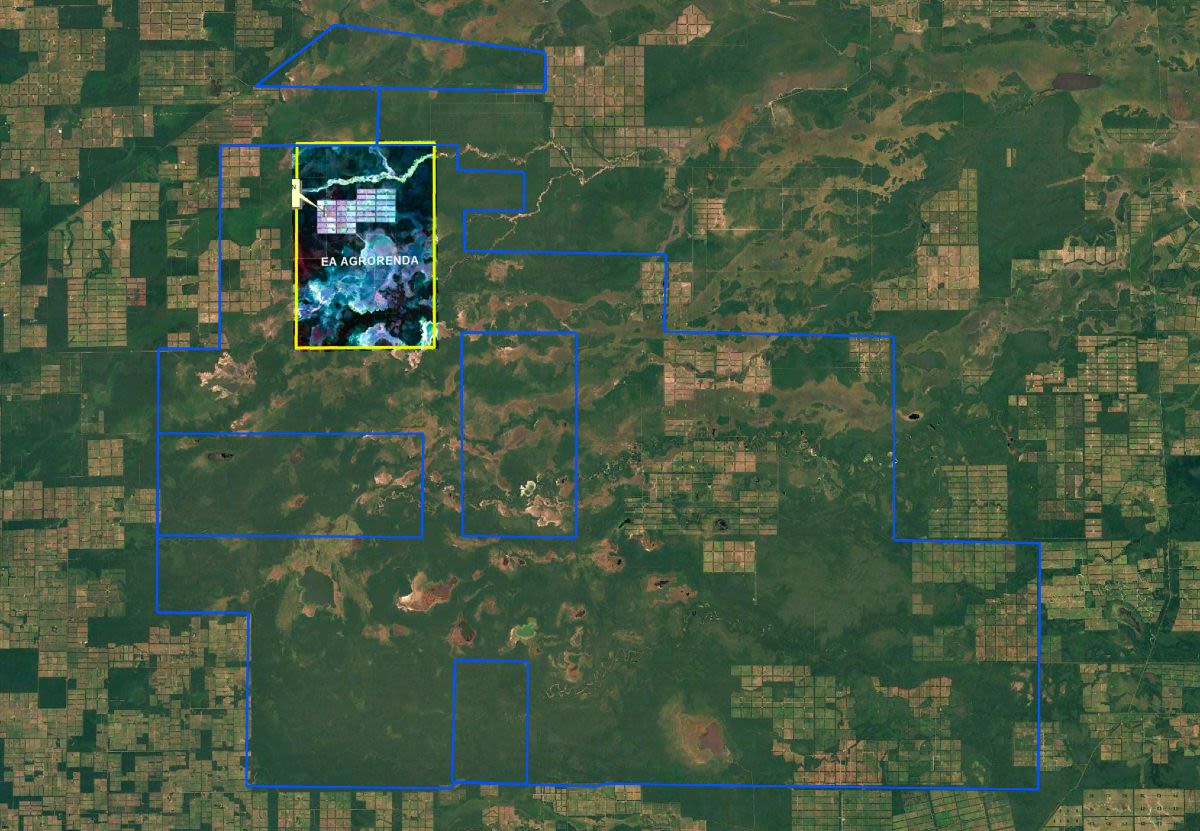

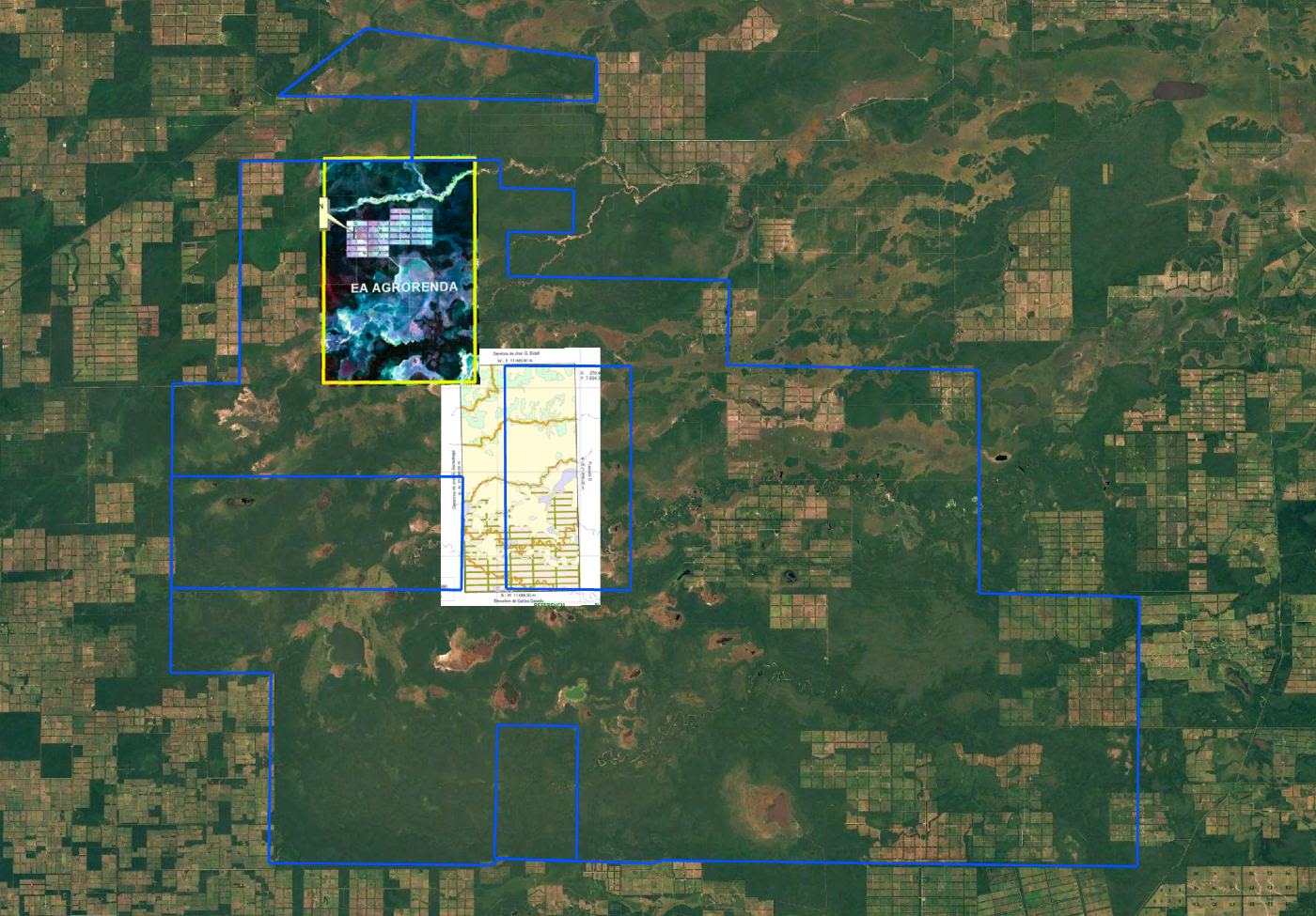

The first property covers 31,677 hectares in the north of PNCAT. Named AgroRendá, it is currently a functioning cattle ranch belonging to a Uruguayan owner, with a herd of 2600 heads of cattle.

GD Agronegocio’s sales material detailed that the ranch has 2400 hectares of planted pasture and 9308 hectares of natural pasture. Earthsight asked about the possibility of clearing forest to expand this total - an action that, as well as being prohibited by the IACHR’s protective measures, is unequivocally illegal under a February 2018 resolution from the country’s forestry institute, Infona.

The firm’s sales representatives, however, assured us that we could easily acquire the documentation necessary to authorise further clearances.

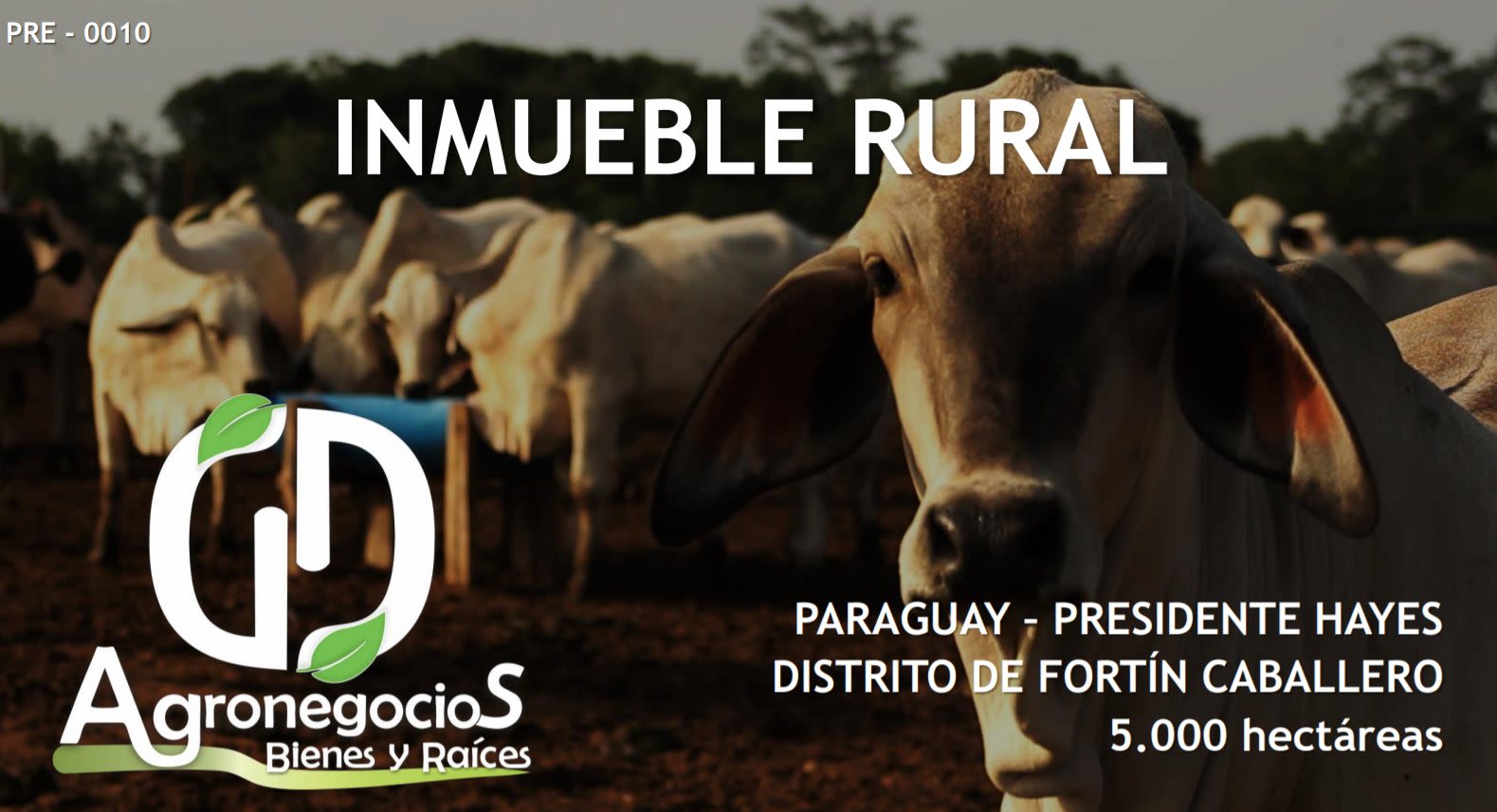

Marketing materials advertise the services of GD Agronegocios.

Marketing materials advertise the services of GD Agronegocios.

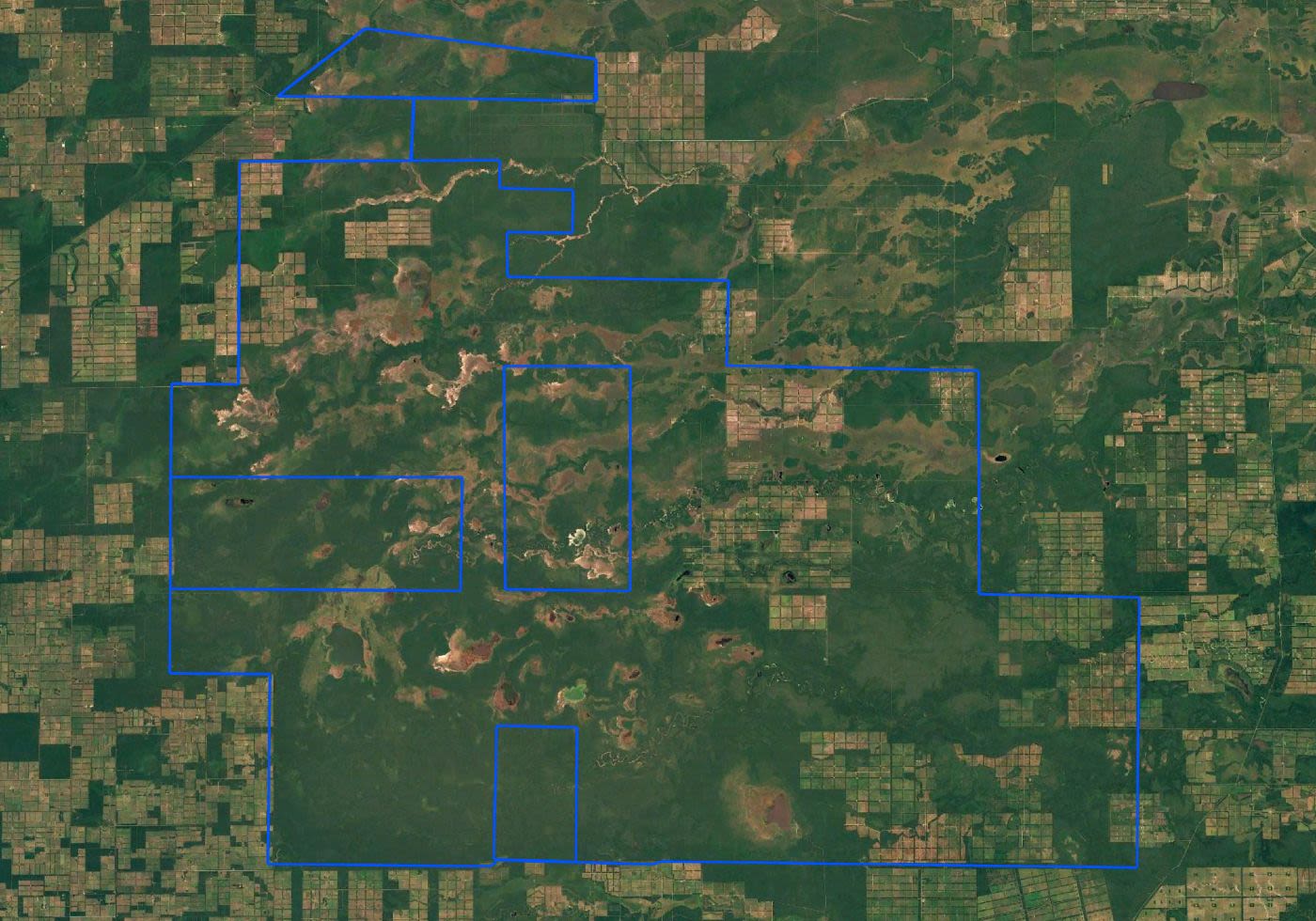

Boundary of PNCAT and proeprties within it formally titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode. © Google Earth

Boundary of PNCAT and proeprties within it formally titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode. © Google Earth

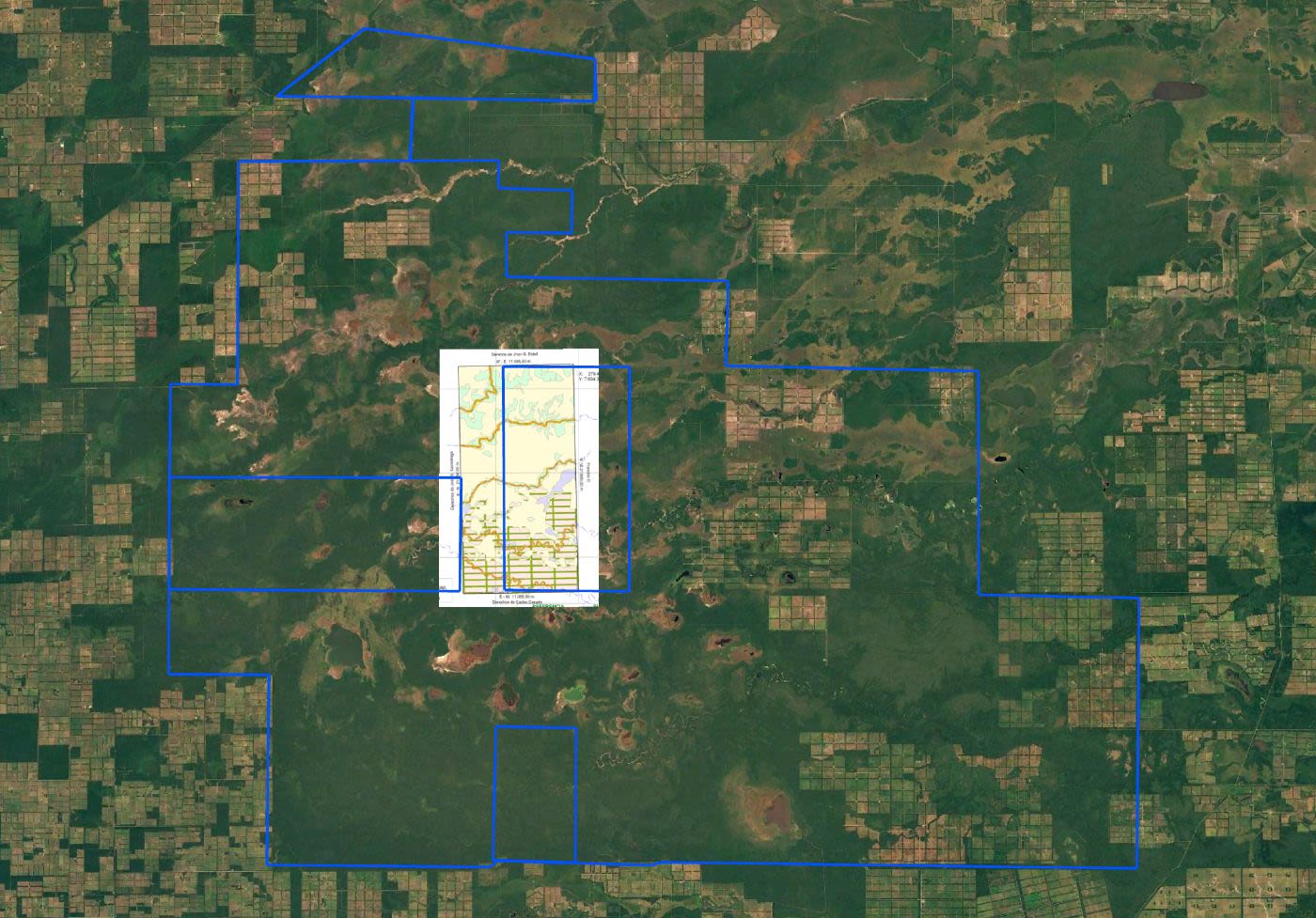

Location of AgroRenda property offered to undercover researchers within the Ayoreo Totobiegosode territory PNCAT . © Google Earth

Location of AgroRenda property offered to undercover researchers within the Ayoreo Totobiegosode territory PNCAT . © Google Earth

Illegal deforestation observed by Earthsight at a cattle ranch within PNCAT in 2019. © Earthsight

Illegal deforestation observed by Earthsight at a cattle ranch within PNCAT in 2019. © Earthsight

“They support 99 per cent of the projects that apply, because this is a country that wants to develop. It’s all very fast. Everything can be obtained here: if you look for it, you will get it,” one representative told undercover researchers.

“There will be no problems at all, I have a friend that’s in the environment ministry, an engineer, and if the moment comes that you can’t acquire something, he’ll help you”.

Earthsight then asked if there might be any issues with indigenous groups or other local communities, who could oppose the expansion plans. The same representative repeatedly denied the existence of any such risks.

Footage of Earthsight's undercover meeting with GD Agronegocios in a shopping centre in Asuncion.

Footage of Earthsight's undercover meeting with GD Agronegocios in a shopping centre in Asuncion.

“The natives don’t have any problems,” he said. “There are zero problems in this area, it is the future of Paraguay … Ten times over: there is no risk”.

The firm’s owner, German Drachenberg, who talked with our prospective buyers by phone from the southern city of Encarnacion, went a step further.

He assured us that we could begin clearing forest before even receiving authorisation from the environment ministry. Once proposals have been submitted to the authorities, he averred, “you can get to work without any problems.”

“Before receiving a license?” Earthsight asked, feigning mild confusion. “Exactly, exactly,” Drachenberg responded. He then gave the example of buying 10,000 hectares of forested land, submitting an impact assessment, and starting to clear forest before the approval comes back.

These claims reflect testimony given to Earthsight by former environment ministry employee Karen Colman.

While working in the ministry’s biodiversity department, Colman discovered that dozens of cattle ranching firms were applying for permits to clear forest that they had already cut down.

They were doing precisely what Drachenberg described: deforesting first and seeking permits to regularise the clearances afterwards. When Colman sought to challenge this practice, her superiors took the side of the ranching firms, as recounted in Earthsight’s investigation Inside the Environment Ministry.

Karen Colman, a former MADES employee, spoke to Earthsight about the culture of corruption that exists in Paraguay's environment ministry. © Earthsight

Karen Colman, a former MADES employee, spoke to Earthsight about the culture of corruption that exists in Paraguay's environment ministry. © Earthsight

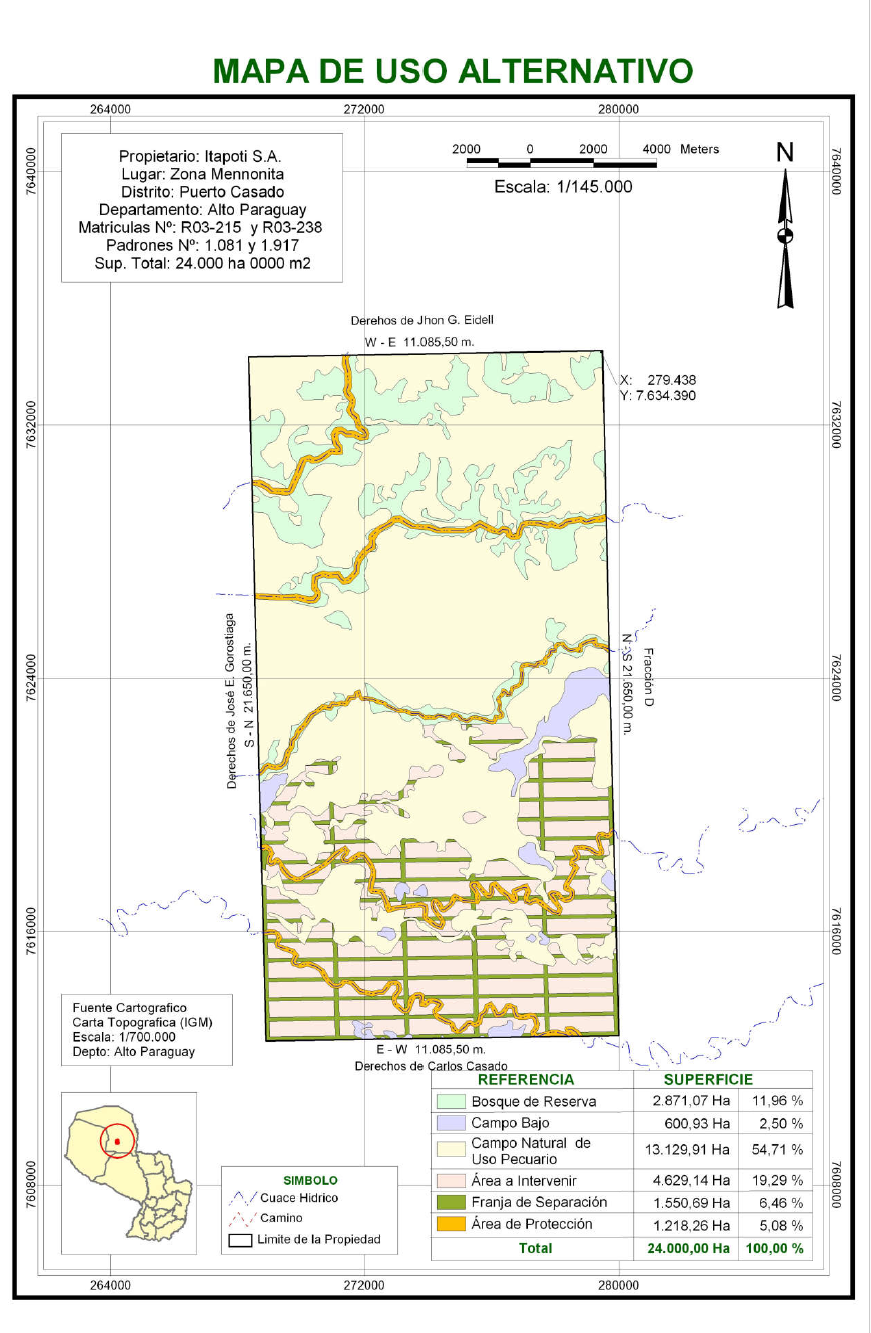

Undercover Earthsight researchers were also offered a 24,000 hectare property in PNCAT by the land dealers © GD Agronegocios

Undercover Earthsight researchers were also offered a 24,000 hectare property in PNCAT by the land dealers © GD Agronegocios

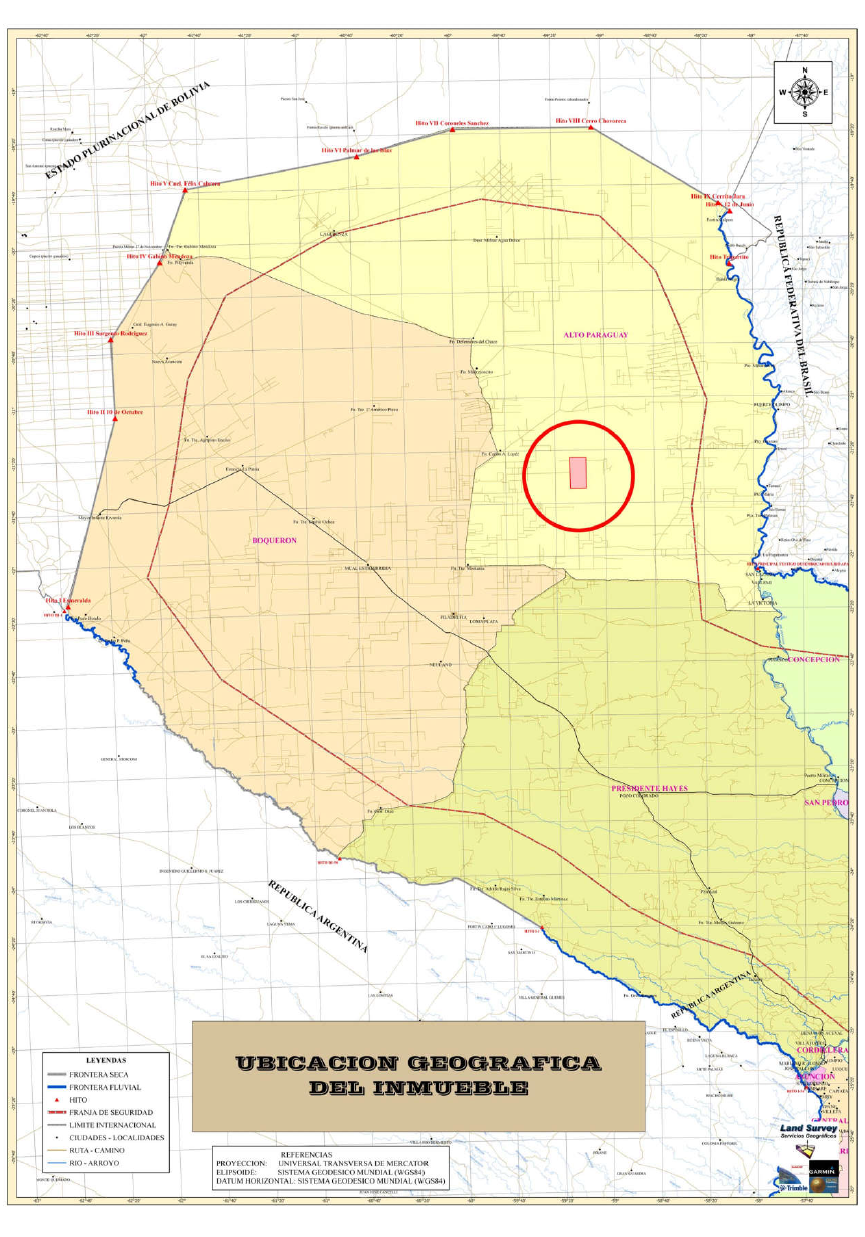

GD Agronegocios provided maps to show the property location within Paraguay. © GD Agronegocios

GD Agronegocios provided maps to show the property location within Paraguay. © GD Agronegocios

The 24,000-hectare property within PNCAT that GD Agronegocios offered to sell undercover researchers is located on land formally titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode. © Google Earth

The 24,000-hectare property within PNCAT that GD Agronegocios offered to sell undercover researchers is located on land formally titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode. © Google Earth

After concluding the face-to-face meeting with GD Agronegocios, Earthsight researchers continued to liaise with the firm’s representatives over WhatsApp. A few hours after leaving the shopping centre, a message came throuh offering a second property of 24,000 hectares within the Totobiegosode territory.

This time, the property was officially titled to the Ayoreo Totobiegosode themselves.

Again, the representatives said there would be no problems clearing forest or installing a ranch on the land. To back up this claim, they shared a fragment of an environmental license for the property. “It’s all forest, with native trees,” one representative said in a recorded voice note.

“It’s all ready to be developed. You’re not going to have any problems. All the properties are totally ready for development”. She then invited Earthsight to join her for a flight over the properties.

To clarify the legal situation around the attempted sale of this property, Earthsight talked with a lawyer, Julio Duarte, who has supported the Totobiegosode land claim.

Duarte recognised the holding in question and explained that it had been the subject of a dispute between the Ayoreo Totobiegosode and an Argentinian ranching firm called Itapoti SA. Both sides claimed to hold land titles that overlapped with each other, with Itapoti claiming two titles totalling 24,000 hectares and the Ayoreo claiming a single title of 26,000 hectares.

In early 2015, Itapoti invaded part of the territory titled to the Ayoreo, installing fenceposts and other infrastructure in preparation to clear forest. The Ayoreo fought back, tearing down the fencing and filing a criminal complaint for land invasion. Following this, both the Ayoreo and Itapoti started legal land measurement procedures on their properties to determine the boundaries of their landholding.

However, while the Ayoreo completed their measurement and had it legally validated, confirming they possess 26,000 hectares, Itapoti never did. Duarte explained that this is because, in reality, they have a potential claim to a property of just 9000 hectares, not 24,000 hectares.

“The sale is a trap,” Duarte explained, pointing out that the license shared with us by the GD Agronegocios representative didn’t have a date and almost certainly expired years ago. If a foreign firm bought the property, they would likely find they were unable to obtain authorisation to develop it - although of course, if they were to follow the advice of GD Agronegocios, they would submit an impact assessment and begin destroying some of the remaining PNCAT forest before receiving any reply.

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegesode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching. © Survival InternationalGAT

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegesode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching. © Survival InternationalGAT

The locations of the two properties within PNCAT offered by GD Agronegocios. © Google Earth

The locations of the two properties within PNCAT offered by GD Agronegocios. © Google Earth

GD Agronegocios owner German Drachenberg. © Facebook

GD Agronegocios owner German Drachenberg. © Facebook

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in Paraguay. © Earthsight

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in Paraguay. © Earthsight

Responding to our findings, GD Agronegocios’ owner German Drachenberg told Earthsight the properties offered had legal titles, current use plans and approved environmental impact studies. He did not deny that one of the properties overlapped land formally titled to the Totobiegosode, instead claiming “we can safely carry out any transaction related to buying and selling or leasing” the land concerned.

Nor did Drachenberg deny he had asserted that forest clearances could occur prior to impact assessments being approved. Nonetheless, he said: “Can deforestation be carried out? Yes, it can be done, but within what is contemplated by the environmental impact law and this must be carried out under studies and approval by the authorities”.

Finally, Drachenberg argued that if prior owners of the properties offered had acted illegally “it is not a matter for our company”, while also stating that officials “must investigate cases of firms and owners who did so without respecting the laws that govern it”.

The attempted sale of these properties - amounting to over 10 per cent of PNCAT - highlights not just the vulnerability of the Totobiegosode forests, but the risks inherent in doing business in areas with such weak institutional oversight.

It also demonstrates the flaws in the enforcement strategy laid out by the legal director of Paraguay’s Forestry Institute, Victor Gonzalez.

Gonzalez told Earthsight that state institutions are often willing to regularise forest clearance that has already taken place, so long as it complies with basic requirements such as the maintenance of a forest reserve. Such lenient policies leave some of the country’s most precious forests perilously exposed - threatening the history, heritage and livelihoods of the indigenous peoples that call them home.