There Will Be Blood

The Ugly Truth Behind Cheap Chicken

Introduction

This is a story which takes in ritzy celebrity-studded birthday parties in gilded mansions. But also brutal murder.

It features one of a handful of businesspeople whose actions helped spark the environmental catastrophe which has swept Brazil in the last few decades. They and their ilk have grown rich from the destruction of vast tracts of its precious tropical forests, bringing devastation to the people dependent on them. It also features one of Brazil's most prominent indigenous rights defenders, and a powerful tale of bravery and defiant hope on the part of his family and community, against all the odds.

On its own, it is a shocking tale, and one which demands justice in Brazil and action by the Western brands to which it is linked. But it is more than that. There are a multitude of similar cases equally deserving of attention, but which remain unexplored. This story therefore holds much wider lessons, both for Brazil and the world.

It exposes the shadowy, complex links involving multiple countries and commodities which characterise the nexus of money, corruption, land grabbing and environmental destruction which plague Latin America. But most of all, it shows that even when the forest is long gone, the story is far from finished – and neither are Western consumers' responsibilities.

The world is beginning to recognise those responsibilities. But in the legislative efforts underway in Europe and the US to sever ties to deforestation and human rights abuses overseas through the consumption of commodities, the devil is in the detail. And the details are not yet right.

Read the pdf

1. A landscape of violence

Marcos Veron © Ricardo Funari / BrazilPhotos

Marcos Veron © Ricardo Funari / BrazilPhotos

Valdelice Veron © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Valdelice Veron © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

In the dark, early morning hours a peaceful silence fills the encampment in rural Brazil where Guarani Kaiowá men, women and children rest after a momentous journey back to those lands.

Alas, that peace was not to last. The dozens of armed men who stormed the camp moments later were determined to inflict all the terror and pain necessary to drive the indigenous people away for good. Following the attack, prominent Kaiowá leader Marcos Veron lies dead on the ground after being mercilessly beaten.

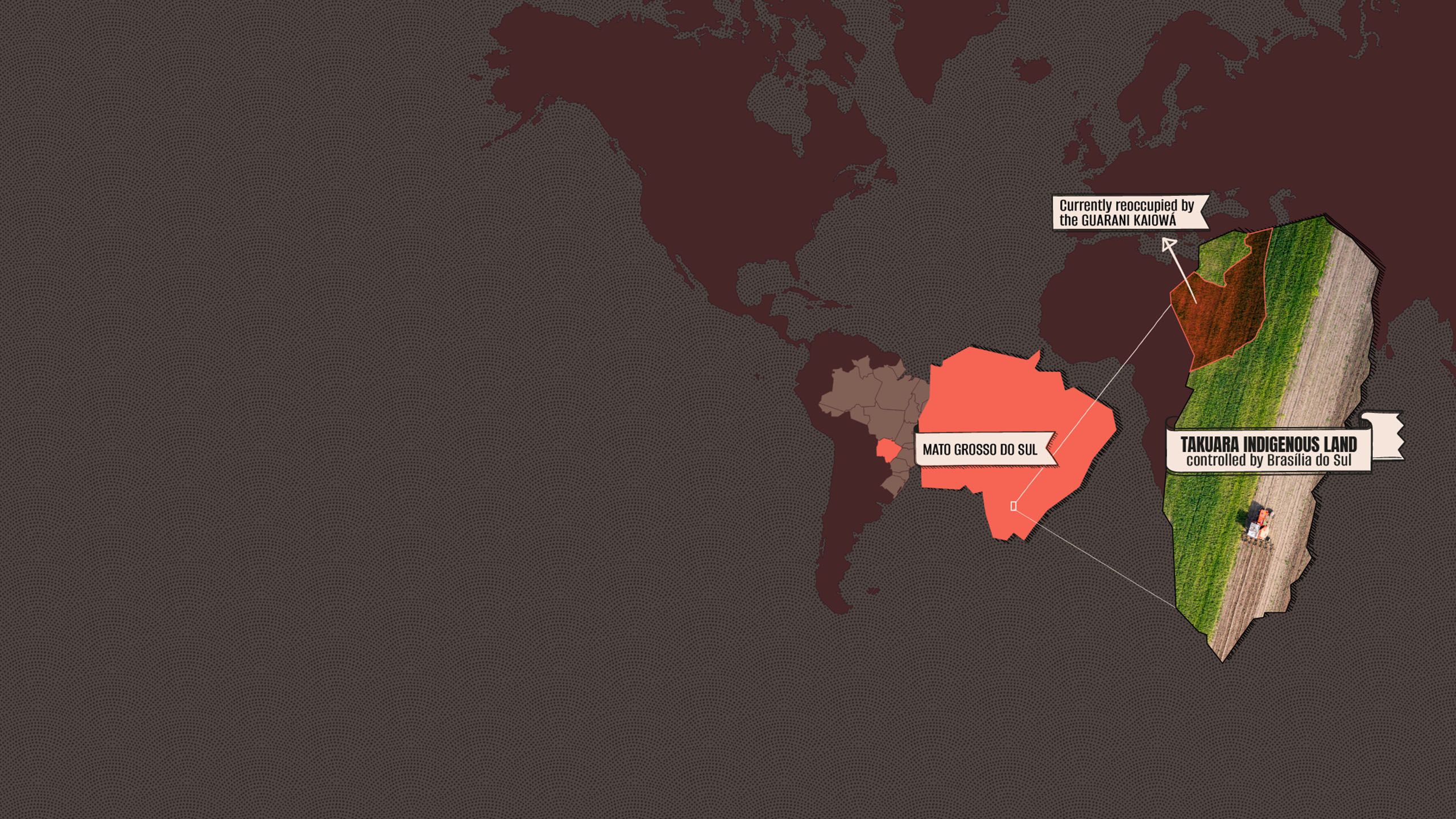

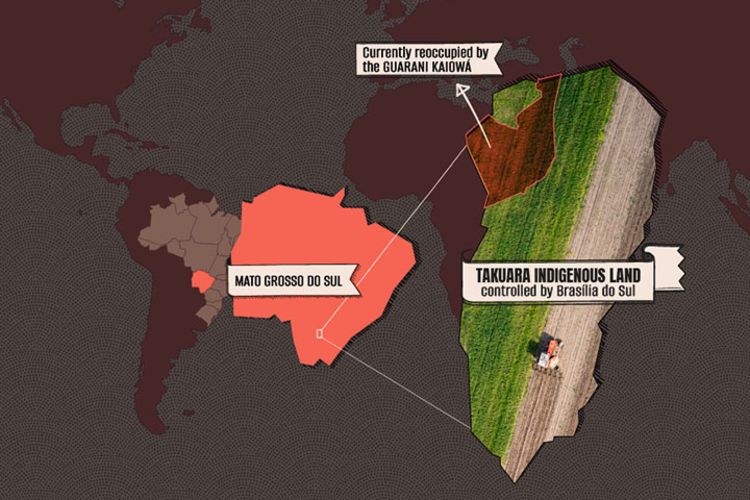

These shocking events took place in Takuara, the sacred land where countless generations of Guarani Kaiowá had lived in harmony with nature.

But they are no longer welcome. As this investigation by Earthsight and Brazilian agribusiness watch group De Olho nos Ruralistas will show, Takuara is now a profitable soy farm inconspicuously but closely connected to household brands used by unsuspecting consumers across Europe.

* * *

Valdelice Veron lists the members of her family killed during the decades-long struggle for their ancestral lands. It's a long list. Among them is her father, still remembered for his courage and charisma. While she has drawn much inspiration from him, Valdelice has become an important Guarani Kaiowá leader in her own right.1 "Every time they kill a Veron, 10,000 Verons will rise up," she says. Valdelice remains firm her community will not give up their dream.

"Many massacres have happened for us to be here today. We're here because this is our sacred land, it's where we have our history and our memory. It's our Tekohá and we don’t forget it."

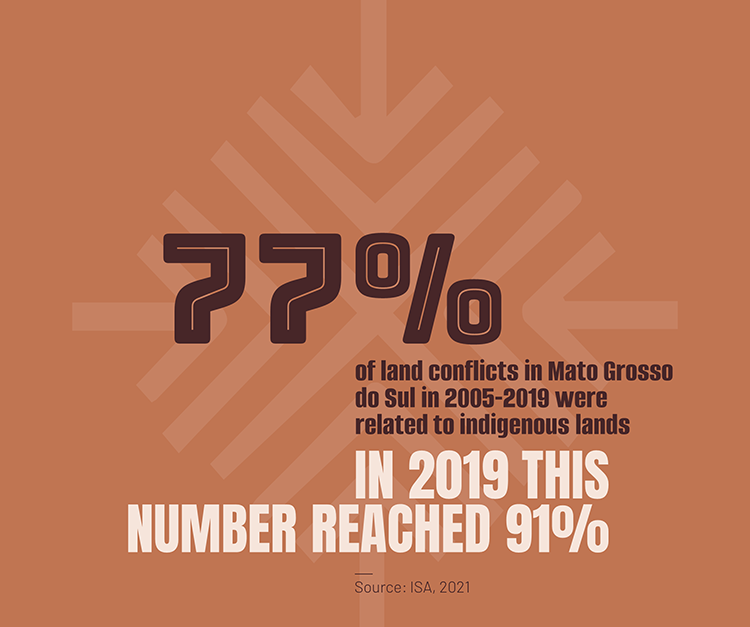

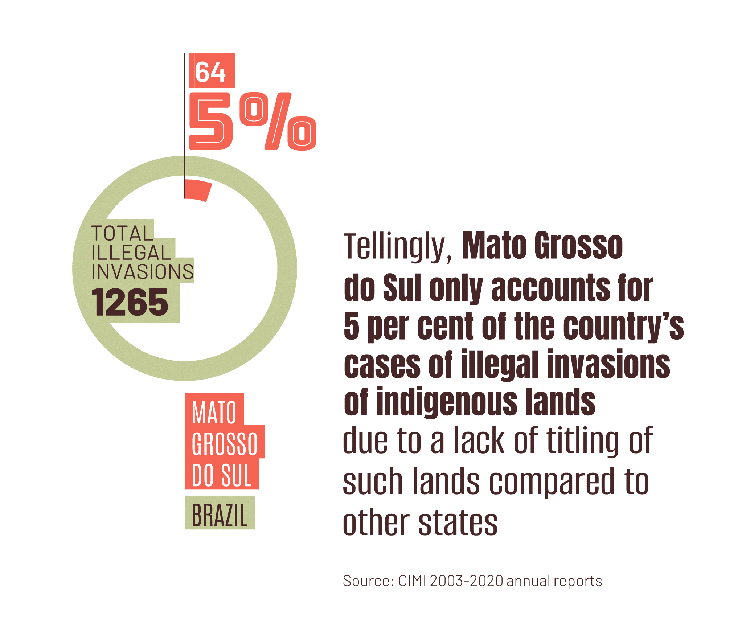

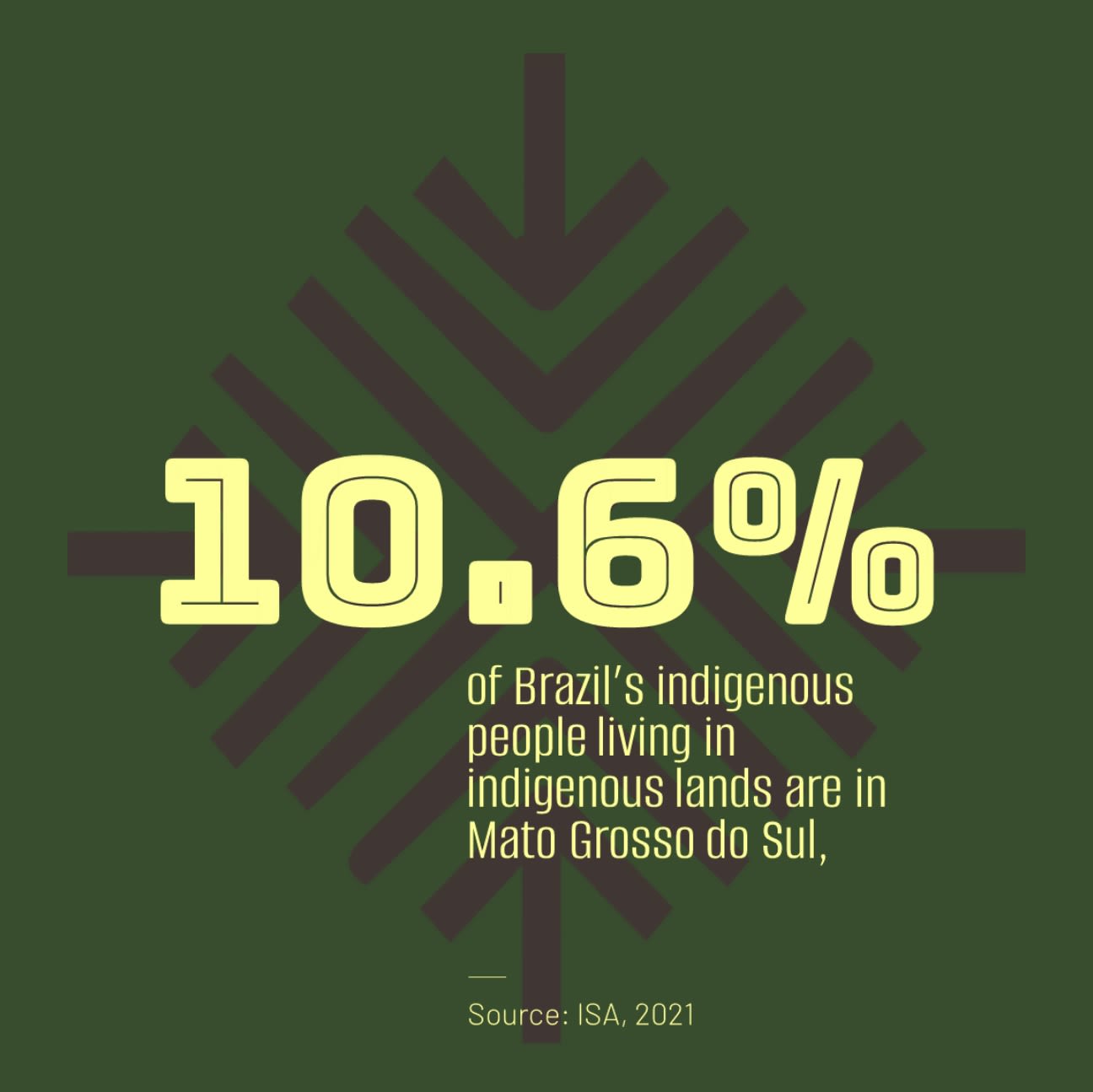

While encroachment of indigenous territories in the Amazon has recently received much attention, the lesser-known Brazilian state of Mato Grosso do Sul, outside the Amazon biome, has a long history of egregious indigenous rights violations, not least against the Guarani Kaiowá people. Experts interviewed by our team were not afraid to use the terms genocide and extermination to describe this reality.2

Mato Grosso do Sul leads national rankings of killings of indigenous people, as well as of suicides and other social ills among indigenous communities due to extreme levels of deprivation and violence.3

The state is located in Brazil's centre-west region. Most of its territory falls within the Cerrado biome, although its northwest is dominated by the swampy lands of the Pantanal and its south-eastern tip by what little remains of the Atlantic Forest.4

It is in this state where the Guarani Kaiowá lived for millennia in numerous communities and in peace with the environment, without polluting its rivers or destroying its forests – a state of affairs that would drastically change following their expulsion from the land.5 One such community was Takuara, located in the municipality of Juti.

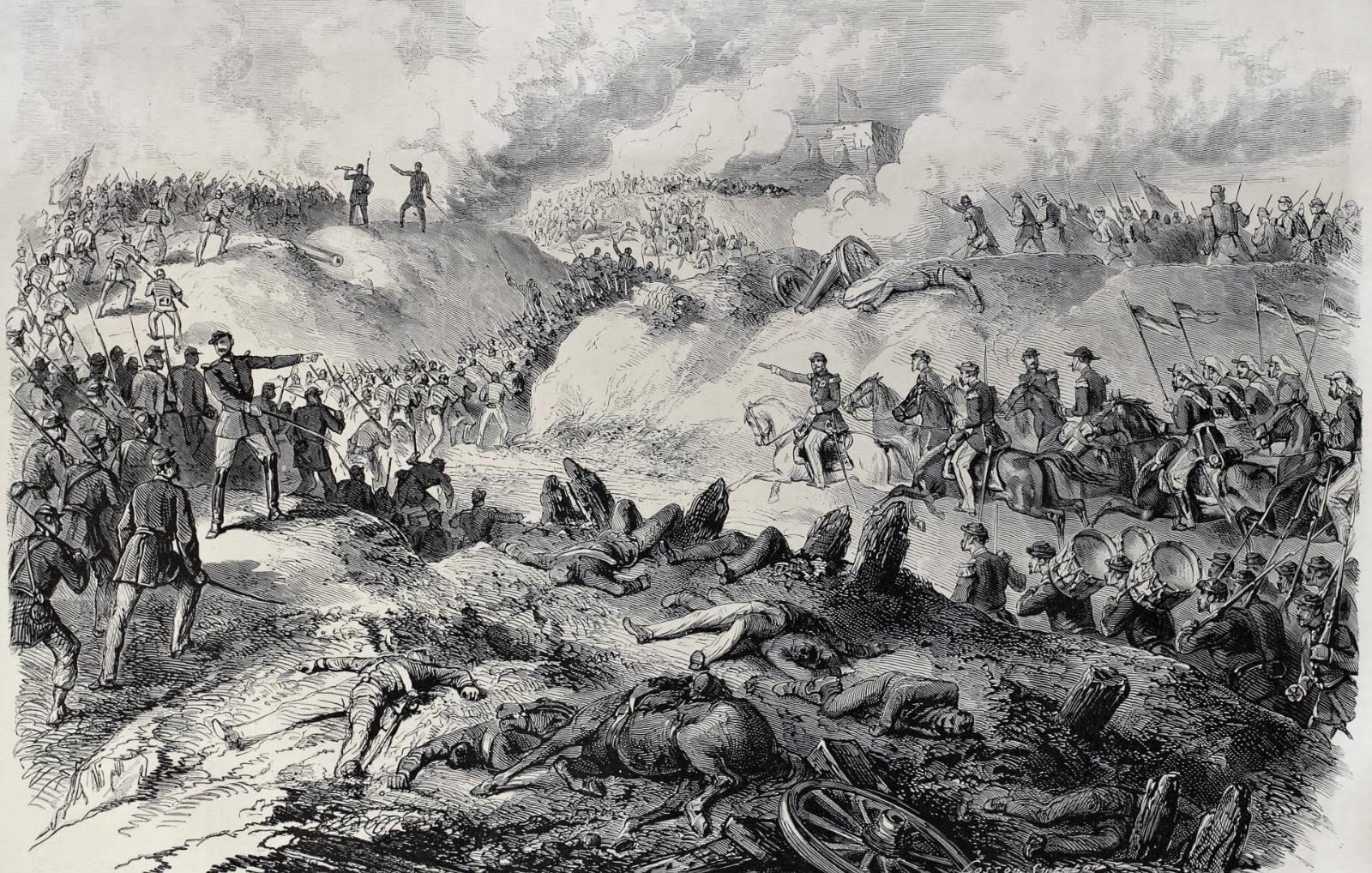

The War of the Triple Alliance was fought between Paraguay and a coalition of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay © Janet-Lange and Cosson-Smeeton after sketch of Paranhos (1868)

The War of the Triple Alliance was fought between Paraguay and a coalition of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay © Janet-Lange and Cosson-Smeeton after sketch of Paranhos (1868)

SPI visit to the Nambikwara indigenous group (1930-50) © Acervo LISA / USP

SPI visit to the Nambikwara indigenous group (1930-50) © Acervo LISA / USP

White settlers have been in contact with indigenous people in Mato Grosso do Sul for centuries.6 Yet it was not until after the War of the Triple Alliance (1864-1870)7 that an intense period of economic expansion in the region began. This period would eventually culminate in the large-scale displacement of Guarani Kaiowá and other indigenous peoples in Mato Grosso do Sul, as the history of Takuara illustrates.

Following the war, the Brazilian government granted millions of hectares in concessions in the region to Companhia Matte Larangeira to grow yerba mate, a plant used to make tea.8

The heyday of Matte Larangeira in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries coincided with the Brazilian state's early efforts to 'pacify' relations between indigenous people and white settlers. In 1910, the Indian Protection Service (SPI) was created. Contrary to what its name suggests, SPI implemented the official state policy of forcibly removing indigenous communities from their ancestral lands and confining them to 'reservations' to make way for agribusiness expansion.9, 10

Brazilian authorities saw indigenous communities as an impediment to progress. More than that, their presence was wilfully ignored. Anthropologist Levi Marques Pereira, who has studied Mato Grosso do Sul indigenous history for decades, told our researchers that "the state saw the territory as unoccupied. Indigenous communities were disregarded."

Removals were often violent, with accounts of children drowning while attempting to flee, women being raped, men beaten, and houses set on fire. Those who resisted or fled the reservations to return to their lands were branded 'savages' and either killed or sent to 'reformatories'.11

Life within the reservations was grim. The SPI appointed so-called 'captains' among the indigenous people to maintain order. Communities were not allowed to perform their traditional prayers or rituals without their permission. Beatings, torture and restrictions of movement were common.12 "To a large extent, the reservation was akin to a concentration camp," Pereira said.

It was within this context that the Guarani Kaiowá from Takuara found themselves in the crosshairs of authorities and businessmen. Despite Matte Larangeira's activities in the region, the Guarani Kaiowá held out in Takuara until the early 1950s.

With yerba mate in decline due to political pressures for the expansion of coffee and other crops, Matte Larangeira was keen to sell its increasingly unprofitable lands.13 The company initially offered the Guarani Kaiowá compensation to move out of Takuara.14 But after they refused, in 1953 SPI and police forces torched their houses and violently moved the community to the Caarapó Reservation, several kilometres away.15 The episode was traumatic. The bodies of two Kaiowá were found incinerated, and one child drowned while being chased.

With the community out of the picture, Matte Larangeira sold its 9,300 hectares of Takuara to coffee baron Geremia Lunardelli.16

Since then, the lives of the Guarani Kaiowá and other indigenous communities in Mato Grosso do Sul have seen little improvement. The SPI is long gone17, but with communities still lacking access to their ancestral lands, now dominated by large plantations and cattle ranches, its dark legacy lives on. Gruesome attacks against communities perpetrated by armed militias and state forces – often leaving behind a trail of death, physical and psychological trauma – have continued.18

Historian Rosely Stefanes of the Mato Grosso do Sul State University told Earthsight and De Olho nos Ruralistas that "indigenous people in Mato Grosso do Sul are treated like dogs. Their humanity is stripped away so they can be killed. These killings are meant to instil fear in the communities."19

Yet Mato Grosso do Sul is also a place of hope and resistance. Out of this cruel reality, brave indigenous men and women have sacrificed much, including their own lives, to defend their peoples' rights.

2. The struggle for Takuara

"The courts allow the farmer to stay but not the indigenous people. We have to wait outside. It's always been that way."

Marcos Veron, Valdelice's father, had a tough childhood. According to some accounts, both his parents were murdered by a farm overseer before he was 10. As a young man he ended up in one of SPI's reservations, where he reportedly endured forced labour.20 Veron is said to have become acutely aware of his people's suffering from an early age. His life-long activism bears this out.

From the 1960s to the early 2000s Veron was a prominent leader in indigenous struggles in Mato Grosso do Sul, acquiring national and international notoriety for his powerful oratory and conviction. The state, however, saw things differently. During that period, Veron was twice imprisoned21 for supporting communities attempting to reclaim their ancestral lands from agribusiness.22

The aim of these incursions, known in Brazil as retomadas23, was to pressure the federal government to officially recognise ill-gotten farmland as traditional indigenous lands. Brazilian law provides the legal basis for such policy, although successive governments have failed to fulfil this mandate.

The retomadas came at a high human cost – with killings and episodes of cruelty committed against indigenous men, women and children – as repression against them grew from the 1970s onwards. According to Valdelice, it was common for civilian and military police to act alongside private gunmen hired by farmers to stop the indigenous returnees.24

After being in the hands of the Lunardelli family for several years, 'Takuara'25 was sold in 1966 to cattle rancher Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho. Renamed Brasília do Sul in 1979, the 9,300-ha farm quickly became a model of efficiency in the region, boasting up to 10,000 heads of cattle by the 1990s. Da Silva Filho's acquisition of the land, which had remained largely forested under the previous owners, ushered in a period of intense deforestation for the creation of pastures.

The entrance sign for Brasília do Sul bears the name of the late cattle baron Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho, who bought the land in 1966 © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

The entrance sign for Brasília do Sul bears the name of the late cattle baron Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho, who bought the land in 1966 © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

The Guarani Kaiowá confined in the Caarapó Reservation, of course, saw none of the profits Brasília do Sul was reaping from their land.26 By 1999 Marcos Veron and his community had had enough. In the early evening of 27 April, they entered the northwest corner of Brasília do Sul and camped over an area of just under 100 hectares. Brasília do Sul owners immediately sued for repossession of the area. The family argued the farm had been legally purchased in 1966 and had all the necessary property titles and registration.

A local judge in Caarapó acted swiftly, in a display of judicial efficiency rarely seen in the country. On 29 April, she issued an eviction order against the Kaiowá and requested the Federal Police to oversee the operation.27 However, the community successfully resisted its removal.

Over the following months Funai – the federal agency that replaced the SPI and is tasked with protecting indigenous rights – took up an intense legal battle for the right of the Kaiowá to occupy their ancestral lands. In the meantime, the community stayed put and started growing vegetables and building prayer houses.

Brasilia do Sul lawyers presented land surveys conducted in the 1920s and 1950s28 claiming there had never been evidence of an indigenous presence in the area. To corroborate these views, the family commissioned anthropologist Hilario Rosa to visit the farm in July 1999. Based on this visit, Rosa concluded that no indigenous people had ever lived in Takuara. Rosa and Brasília do Sul lawyers accused Funai of being controlled by "revisionist anthropologists" working on behalf of ideological NGOs and external actors.29

Funai's lawyers claimed the local judge in Caarapó had no authority to rule over a federal matter that involved indigenous land disputes.30 The case was soon moved to a federal court.

Funai requested time to conduct a study of the area to clarify whether the Kaiowá had traditionally occupied it. Even before such a study could be concluded, the agency already knew of the Kaiowá’s long history at Takuara based on a 1983 field study.31

Funai's lawyers also argued the Guarani Kaiowá's eviction in 1953 was blatantly illegal and represented a major failure by the SPI and Brazilian government to safeguard the community's land rights, which were protected under the law.32

Funai's arguments were to no avail. In September 1999, a federal judge requested police forces to oversee the community’s eviction from Brasília do Sul. But again, the community – now numbering around 250 – resisted.33

In a preliminary analysis released in January 2001, Funai concluded Takuara was indeed Kaiowá land. It didn't matter. In October the community was violently evicted by police forces and Brasília do Sul's private security following a federal court order.34

Heralding worse things to come, Marcos Veron and other members of the community were shot at and handcuffed, and their houses were destroyed.35

"When you hear there's going to be an eviction in indigenous land in Mato Grosso do Sul you can conclude that the judge signed off on our deaths," Valdelice says. "When we're not struck by gunmen we're struck by the courts."

She vividly remembers her father's words to her that harrowing day: "We're going to surrender now but we'll come back, and we won't leave again. I won't leave again." In a tragic way, he was right.

"The courts allow the farmer to stay but not the indigenous people. We have to wait outside. It's always been that way."

Marcos Veron, Valdelice's father, had a tough childhood. According to some accounts, both his parents were murdered by a farm overseer before he was 10. As a young man he ended up in one of SPI's reservations, where he reportedly endured forced labour.20 Veron is said to have become acutely aware of his people's suffering from an early age. His life-long activism bears this out.

From the 1960s to the early 2000s Veron was a prominent leader in indigenous struggles in Mato Grosso do Sul, acquiring national and international notoriety for his powerful oratory and conviction. The state, however, saw things differently. During that period, Veron was twice imprisoned21 for supporting communities attempting to reclaim their ancestral lands from agribusiness.22

The aim of these incursions, known in Brazil as retomadas23, was to pressure the federal government to officially recognise ill-gotten farmland as traditional indigenous lands. Brazilian law provides the legal basis for such policy, although successive governments have failed to fulfil this mandate.

The retomadas came at a high human cost – with killings and episodes of cruelty committed against indigenous men, women and children – as repression against them grew from the 1970s onwards. According to Valdelice, it was common for civilian and military police to act alongside private gunmen hired by farmers to stop the indigenous returnees.24

After being in the hands of the Lunardelli family for several years, 'Takuara'25 was sold in 1966 to cattle rancher Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho. Renamed Brasília do Sul in 1979, the 9,300-ha farm quickly became a model of efficiency in the region, boasting up to 10,000 heads of cattle by the 1990s. Da Silva Filho's acquisition of the land, which had remained largely forested under the previous owners, ushered in a period of intense deforestation for the creation of pastures.

The entrance sign for Brasília do Sul bears the name of the late cattle baron Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho, who bought the land in 1966 © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

The entrance sign for Brasília do Sul bears the name of the late cattle baron Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho, who bought the land in 1966 © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

The Guarani Kaiowá confined in the Caarapó Reservation, of course, saw none of the profits Brasília do Sul was reaping from their land.26 By 1999 Marcos Veron and his community had had enough. In the early evening of 27 April, they entered the northwest corner of Brasília do Sul and camped over an area of just under 100 hectares. Brasília do Sul owners immediately sued for repossession of the area. The family argued the farm had been legally purchased in 1966 and had all the necessary property titles and registration.

A local judge in Caarapó acted swiftly, in a display of judicial efficiency rarely seen in the country. On 29 April, she issued an eviction order against the Kaiowá and requested the Federal Police to oversee the operation.27 However, the community successfully resisted its removal.

Over the following months Funai – the federal agency that replaced the SPI and is tasked with protecting indigenous rights – took up an intense legal battle for the right of the Kaiowá to occupy their ancestral lands. In the meantime, the community stayed put and started growing vegetables and building prayer houses.

Brasilia do Sul lawyers presented land surveys conducted in the 1920s and 1950s28 claiming there had never been evidence of an indigenous presence in the area. To corroborate these views, the family commissioned anthropologist Hilario Rosa to visit the farm in July 1999. Based on this visit, Rosa concluded that no indigenous people had ever lived in Takuara. Rosa and Brasília do Sul lawyers accused Funai of being controlled by "revisionist anthropologists" working on behalf of ideological NGOs and external actors.29

Funai's lawyers claimed the local judge in Caarapó had no authority to rule over a federal matter that involved indigenous land disputes.30 The case was soon moved to a federal court.

Funai requested time to conduct a study of the area to clarify whether the Kaiowá had traditionally occupied it. Even before such a study could be concluded, the agency already knew of the Kaiowá’s long history at Takuara based on a 1983 field study.31

Funai's lawyers also argued the Guarani Kaiowá's eviction in 1953 was blatantly illegal and represented a major failure by the SPI and Brazilian government to safeguard the community's land rights, which were protected under the law.32

Funai's arguments were to no avail. In September 1999, a federal judge requested police forces to oversee the community’s eviction from Brasília do Sul. But again, the community – now numbering around 250 – resisted.33

In a preliminary analysis released in January 2001, Funai concluded Takuara was indeed Kaiowá land. It didn't matter. In October the community was violently evicted by police forces and Brasília do Sul's private security following a federal court order.34

Heralding worse things to come, Marcos Veron and other members of the community were shot at and handcuffed, and their houses were destroyed.35

"When you hear there's going to be an eviction in indigenous land in Mato Grosso do Sul you can conclude that the judge signed off on our deaths," Valdelice says. "When we're not struck by gunmen we're struck by the courts."

She vividly remembers her father's words to her that harrowing day: "We're going to surrender now but we'll come back, and we won't leave again. I won't leave again." In a tragic way, he was right.

3. The murder of Marcos Veron

"I looked at him, he was all beaten and covered in blood. It didn't even look like him anymore. I didn't want to believe it. I went outside and screamed and screamed with my indigenous brothers."

That Sunday in January 2003 Valdelice was reluctant to leave. The community had returned to Takuara the day before after more than a year camping in difficult conditions by the side of a road. Sitting on a log with her father, she asked him to let her stay. But he was adamant. Valdelice was tasked with notifying federal prosecutors in a nearby town that the Kaiowá had returned to their lands.

"It felt like my last moment with him," she recounts. She left in the afternoon. At 3:30am Monday, while the rest of the community rested around a fire or in tents, cars approached.36 Upon arrival, between 30 and 40 armed men jumped out and began shooting. Members of the community tried to flee but everything happened too fast.

Marcos Veron was dragged out of his tent, repeatedly kicked and struck with the butt of a rifle while on the ground. Other indigenous people were also beaten. One of Veron's daughters, Geisabel, was dragged by her hair and beaten. She was seven months' pregnant. Seven people, including Veron and his son Ládio, were thrown into a red Silverado pickup truck and had their hands bound. Veron was barely conscious. After a several-minute drive, they were dumped next to a road and tortured. Ládio was threatened with being burned alive. Once the attackers had left Veron was taken to a hospital where he arrived lifeless.37 He was 73. Upon hearing the news Valdelice rushed to the hospital only to find her father in an unrecognisable state.

Veron's murder caused a storm, and not only in Brazil. It was reported in the mainstream press as far afield as the UK.38 Tony Blair's government sent condolences. According to Valdelice, his body was taken in procession to Takuara by around 10,000 indigenous people from various ethnicities in Brazil.39 Such was Marcos Veron's reputation. To this day, every 13 January the Kaiowá gather around his grave in Takuara to commemorate his legacy.

What followed was a legal battle to bring the perpetrators to justice, stretching over more than 15 years – one that has never been concluded. A total of 27 people were charged. In 2010 federal prosecutors charged Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho – the man who had overseen the destruction of Takuara's forests for cattle – accusing him of being the mastermind and financial backer of the attack. In 2009 the case against a few of the defendants was transferred to Sao Paulo out of concerns over farmers' political influence in Mato Grosso do Sul. The case against da Silva Filho and several others, however, remained in the state.40

In 2011 three former Brasília do Sul employees were each sentenced to over 12 years in prison for kidnapping, torture, bodily harm, conspiracy to commit a crime, and procedural fraud.41, 42, 43

Antonio Batista Rodrigues, aka 'Rodriguinho', a former military police officer seen by the prosecution as a key figure in the case, was captured in Paraguay in 2019 under an international arrest warrant and extradited to Brazil the following year.44 Rodriguinho was accused by the prosecution of hiring gunmen and supplying firearms for the attack against the community. By the time of his capture, he reportedly had 14 arrest warrants against him for kidnapping, homicide, attempted homicide, and criminal organisation.45

In previous years Rodriguinho's lawyers appealed against such warrants to three different courts. They all denied the request, including the Supreme Court in 2016. Judges pointed to Rodriguinho's status as a fugitive of justice since 2003, when the first arrest warrant against him was issued, his prominent role in the attack, and past charges against him for murder in the state of Roraima.46

Still, according to information provided to Earthsight by the court overseeing the case, Rodriguinho was released on a provisional basis in March 2020 with the requirement to wear an ankle tag for two years. In March 2022, the tag was removed. Rodriguinho still awaits trial.47 It has not been possible to determine his current whereabouts.

Federal prosecutor Marco Antonio Delfino de Almeida, who worked on the case and talked to our team for this report, is critical of Rodriguinho's release: "It was alleged that he posed no risk. That's absurd. The guy was a fugitive of justice, and the judge released him."

To this day, no-one has been convicted of the murder of Marcos Veron.

Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho stood accused of homicide, attempted homicide, torture, kidnapping, conspiracy to commit a crime, and grave threat.48 He never stood trial.

In 2017 a federal judge ruled that the 2010 charges brought against da Silva Filho were time barred as a result of the time that had passed since the crimes and the accused's advanced age. An investigation into his role in witness tampering and evidence forgery to favour the three defendants sentenced in 2011 never led to a conviction.49, 50

With da Silva Filho’s death in 2019 aged 102, most think the whole case is essentially closed. "Had Rodriguinho remained in detention, the case may have moved forward more quickly. That hope is gone," Delfino laments.

Valdelice bemoans the outcome: "There has been no justice because the masterminds [of the crime] were never arrested. Da Silva Filho died peacefully of old age."

4. A people in limbo

Following Marcos Veron's murder, the process to officially recognise Takuara as Guarani Kaiowá land – or 'demarcate' it in the Brazilian parlance – gained momentum. Funai concluded its study in 2005, which laid to rest any doubts about the ancestral presence of the community on that land.51

Levi Marques Pereira, the anthropologist who led Funai's study, is in no doubt that the SPI committed an illegal act by forcibly evicting the Kaiowá, and that the then state of Mato Grosso first sold the land to a private owner in the 1920s without checking for the presence of an indigenous community in the area.52

Satisfied with the weight of the evidence, in June 2010 the Ministry of Justice issued a 'declaration' recognising the Guarani Kaiowá's rights over the area occupied by Brasília do Sul.53 However, two weeks later Supreme Court Justice Cármen Lúcia suspended the demarcation process following a lawsuit by the farm's owners.54, 55

Lúcia alluded to previous court rulings on similar cases that had favoured farmers on the basis of a concept known in Brazil as marco temporal (time frame). The Justice seems to have accepted the view commonly held by some judges – and vociferously promoted by the agribusiness lobby – that if an indigenous community were not in possession of their land in 1988, when the Constitution came into force, it had no legitimate claims over it. This view has been strongly rejected by indigenous communities and rights advocates as unconstitutional.

Driven by extreme poverty, in January 2016 the Guarani Kaiowá expanded the area they had been occupying at Takuara – around 300 hectares – to over 1,500 hectares.56, 57 Tensions escalated again. In February that year the community suffered six consecutive nights of armed attacks and a "relentless siege by armed men."58 The following month a federal judge ordered the community's removal. However, since then both the Supreme Court – twice – and Brazil's Attorney General have ruled against evicting the Kaiowá due to the potential for more bloodshed.59

Since then, the community has been in legal limbo. Dozens of families currently live in precarious conditions in a corner of Brasília do Sul. Some try to make a living in informal plantation jobs.60

Takuara's final status still awaits resolution. None of the court rulings issued over the years have a definitive character. The community's ultimate fate depends on whether the federal government will abide by its constitutional mandate and grant the Kaiowá exclusive rights over their ancestral lands.

Valdelice points to the lasting precariousness of her community's situation nearly 20 years after her father's sacrifice and a stalled demarcation process. "We can't collect roots or medicinal plants. The Jacintho family says this is their private land," she remarks.61 To understand how it's come to this, we need to look deeper into the interplay of power, wealth, politics, race, and justice in one of the world's largest commodity producers and exporters.

5. Meet the Jacinthos

The music video for 'Jacintho' by Brazilian singer-songwriter Gilberto Gil (pictured) charts the eponymous cattle baron's life through family photos. Source: Gilberto Gil / YouTube

The music video for 'Jacintho' by Brazilian singer-songwriter Gilberto Gil (pictured) charts the eponymous cattle baron's life through family photos. Source: Gilberto Gil / YouTube

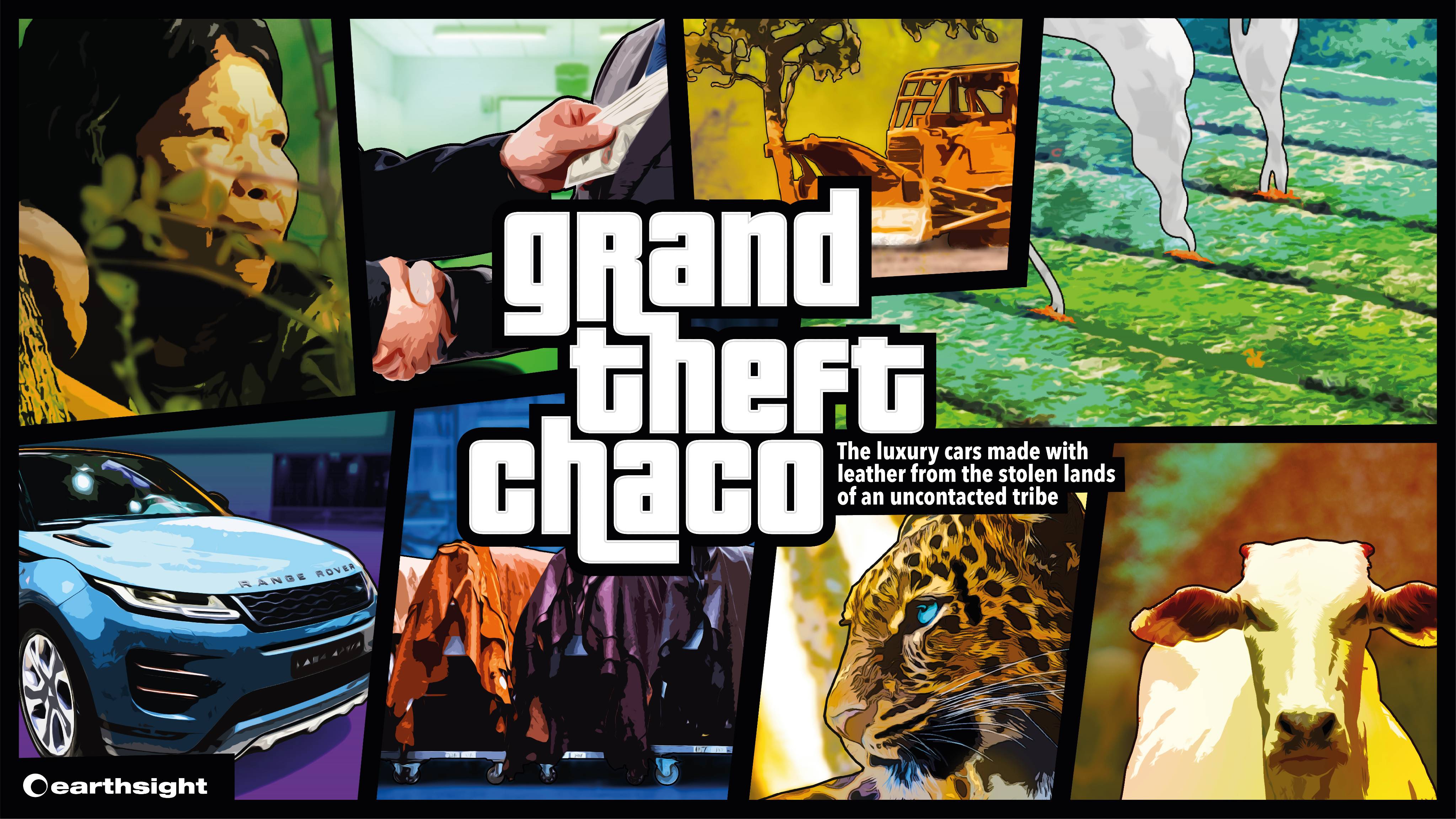

Grand Theft Chaco (2020) © Earthsight

Grand Theft Chaco (2020) © Earthsight

Aerial view of Brasília do Sul © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Aerial view of Brasília do Sul © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Entrance to a ranch owned by Yaguareté Porã, a Brazilian firm linked to illegal clearances in Paraguay © Earthsight

Entrance to a ranch owned by Yaguareté Porã, a Brazilian firm linked to illegal clearances in Paraguay © Earthsight

Jacintho

I envy you somewhat

100 years is not for everyone

What a memorable jamboree. "Joy and sophistication," quipped the lifestyle press.62 Interior designers, chefs and a live band were brought in to provide an unforgettable experience to the 800 black-tie guests who thronged the glitzy mansion in Sao Paulo's exclusive neighbourhood of Jardim Paulistano. Among them were a who's who of Brazilian high society, including a Rothschild, a former justice minister, a Victoria's Secret model, and many more. One of Brazil's most iconic artists, Grammy winner Gilberto Gil, even wrote a song to mark the event.63

The occasion demanded such a shindig. Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho was celebrating 100 years. The centenarian has a special place in Brazilian agribusiness history. In the early 1960s he was part of a small group of pioneers who travelled to India in search of a cattle breed that could thrive in Brazil's tropical climate and withstand its implacable parasites.64 They brought back Nelore, the breed that would revolutionise Brazil's cattle industry and help transform the country not only into the beef powerhouse it is today, but also the largest hotspot of tropical deforestation worldwide.65

A descendant of landowners stretching back to the days of the Empire66, da Silva Filho was already an established cattle rancher in Sao Paulo state when he bought Brasília do Sul in 196667. Still, the new farm quickly became central to the family's wealth. In the late 2000s Brasília do Sul ditched its cattle herd and entered the lucrative soy business.68 In 2012 the farm's total area was officially expanded from its original 9,300 to 9,700 hectares following a request by the Jacintho family to federal authorities.69

Before that, in the early 1990s, da Silva Filho had transferred ownership of Brasília do Sul to his adult children.70

The true scale of the family's landholdings and wealth have proved impossible for Earthsight and its partners to properly assess. What we do know is that the family's businesses include over a dozen farms in Mato Grosso do Sul and neighbouring states totalling at least 50,000 hectares71, some of which have been fined and embargoed by federal authorities for illegal deforestation in the Pantanal biome.72 But it's their ranches across the border in Paraguay that have drawn most attention.

In 2020 Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco report revealed that ranching firm Yaguareté Porã had a long history of illegal land dealings and pasture development within PNCAT, the ancestral lands of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode in Paraguay's Chaco.73 The territory, protected by several government resolutions since the 1990s, is home to some of the last uncontacted tribes in the Americas outside the Amazon.

Yaguareté Porã is owned by Marcelo Bastos Ferraz, who is married to one of da Silva Filho's daughters. Of all the farms researched by Earthsight, Yaguareté's egregious behaviour stood out. In the early 2000s, the firm cut roads deep into the heart of PNCAT, slicing through historic Ayoreo sites, and then used its political influence to acquire a license to clear the surrounding forest. Yaguareté was later fined for concealing information about uncontacted groups in its application for environmental licenses, and in the mid-2010s further cleared thousands of hectares at PNCAT.74

In 2014 Bastos Ferraz met with a delegation of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode and reportedly rebuffed their pleas to stop destroying their ancestral lands.75, 76

Other members of the family have ventured into Ayoreo Totobiegosode lands. Gino de Biasi Neto, the husband of another of da Silva Filho's daughters, owns two ranches at PNCAT called River Plate and BBC, which have stood accused of deforesting thousands of hectares of forests inhabited by the Ayoreo, including over the last two years.77

Back in Brazil, the family has close connections with state governors, ministers, lawmakers and even presidents.78 The family's support for right-wing politicians has been known for several years.79 In 2018 it played its part to help elect Jair Bolsonaro to the presidency.80 As recently as April 2021, Vanda Moraes Jacintho, da Silva Filho's widow, met with Bolsonaro – well known for his anti-indigenous policies – during business gatherings.81

The Jacintho family did not reply to Earthsight's repeated requests for comment.

The Jacinthos are not the only ones to have profited from Takuara. Those who do business with Brasília do Sul are taking their cut, knowingly or not, from a land scarred by cruelty and injustice. Worse, unsuspecting consumers thousands of miles away may be abetting the plight of a people because a chain of exporters, importers, manufacturers, wholesalers and retailers have either not bothered to check the links between their goods and this disaster or have readily ignored them.

6. Soy secrets

"It's as if soy came from nowhere. There's nothing to identify it so the consumer is not able to see that it comes from an indigenous land."

On the face of it, Brazilian chicken may seem a safe bet. Estimates indicate its deforestation risk is 1000 times lower than that of Brazilian beef, because most of the feed is sourced from low-deforestation areas in Brazil's southern regions.82 Yet as this report shows, these regions face their own challenges related to indigenous rights violations, abuse of power, and government failures. Consumers don't just care about forests and would surely also be interested to know if the chicken they buy at the supermarket or their local KFC – or the pet food they feed their dogs and cats – has any reported links to murder and impunity abroad.

Our team found that Brasília do Sul's soy is purchased and processed by some of the world's most important grain traders and two of Brazil's largest cooperatives.83

One of them is Lar Cooperativa Agroindustrial, Brazil's fourth largest chicken slaughtering company. Boasting over 11,000 members and 22,000 staff in the states of Paraná and Mato Grosso do Sul, Lar buys nearly a fifth of all the soy produced in Mato Grosso do Sul.84 With grain storage facilities and a soy processing complex in Caarapó, a municipality near Brasília do Sul, Lar uses soy to produce animal feed for its own members, who raise poultry, pigs, and dairy cattle. Confidential sources on the ground have confirmed to Earthsight that Lar's Caarapó unit receives soy from Brasília do Sul.

Rearing over 1.1 million birds at any given time, poultry farming accounts for a third of Lar's annual revenue of around $1.9 billion. In Caarapó, the cooperative has a crushing capacity of 1500 tons of soy per day.85 Lar, which exports chicken to over 80 countries, expects to double its chicken production by 2024. In order to keep pace with livestock expansion, Lar has invested millions of dollars in growing feed capacity by acquiring new feed mills and building new factories.86 In fact, according to the cooperative, its soy processing facility in Caarapó is part of its "strategic planning focused on expanding meat production in Paraná and receiving grains in Mato Grosso do Sul."87

Since 2020 Brazil has been the world's largest chicken meat exporter and second largest producer.88 Paraná state, where Lar is headquartered, is the country's main producer, accounting for a third of the total.89 Brazilian chicken production and exports have broken records90 in recent years and are expected to keep rising in the near future.91 In September 2021, it was announced Brazil had been in talks to increase export quotas to the UK by about a third.92 British imports of Brazilian fresh, chilled and frozen chicken have already risen 70 per cent in the last five years.93 In January 2022, the EU increased its imports of Brazilian chicken meat by 53.5 per cent compared to the same month last year.94

Trawling through tens of thousands of rows of shipment records we obtained, Earthsight was able to trace how between 2017 and 2021 Lar exported 117,000 tonnes of frozen and marinated chicken products to the EU and UK, with exports in 2021 nearly three times as high as those in 2017. LAR's main markets in the region are Germany, accounting for 42 per cent of exports, the UK (36 per cent), and the Netherlands (15 per cent).95

Lar's most important customer in the UK is Westbridge Foods, a major manufacturer and distributor of chicken products to some of the country's largest retailers and restaurant chains, including Sainsbury's, Asda, Aldi, Iceland, and KFC. Between 2018 and 2021 Westbridge imported nearly 38,000 tonnes of frozen and marinated chicken from LAR, accounting for a third of all Lar chicken exports to the EU and UK in the period.96

Westbridge claims to be a supplier to "all the major retailers in the UK", including premium and discount retail brands, as well as high end restaurants, gourmet pubs, and restaurant chains.97 Sainsbury's stocks Westbridge's Valley Foods brand, including chicken fillets and chicken breast strips. In recent years KFC has awarded multiple supplier awards to Westbridge, "a longstanding KFC partner who's [sic] desire to generate a better KFC world just continues to grow and grow."98

Westbridge, KFC and Iceland did not respond to Earthsight's requests for comment. Aldi stated that the chicken they source from Westbridge has no links to Brasília do Sul. Asda said its Westbridge chicken does not come from "this continent" (possibly meaning South America). Sainsbury's stated that the chicken supplied to it by Westbridge and sold as Sainsbury's "own brand" does not come from Lar. When asked about Valley Foods, the company replied that "as Valley Foods is a branded product you would need to speak to the manufacturer." But as stated above, Westbridge did not answer our questions.

Both Sainsbury's and Aldi added that they are continuing to investigate the matter with Westbridge. Asda, Aldi and Sainsbury's emphasised their commitments to respecting human rights throughout their supply chains and sourcing sustainable soy (see their full responses here). All three retailers seem to be relying solely on Westbridge's assurances about the origin of their chicken.

When asked for evidence to support their claims of not having any links to Lar or Brasília do Sul, Aldi and Asda provided almost identical responses and pointed to their use of Global Food Safety Initiative (GFSI) certification as proof of traceability.

We questioned Aldi and Asda further on the relevance of the GFSI to this investigation but neither responded. GFSI is a food safety programme and not designed to monitor indigenous rights violations.

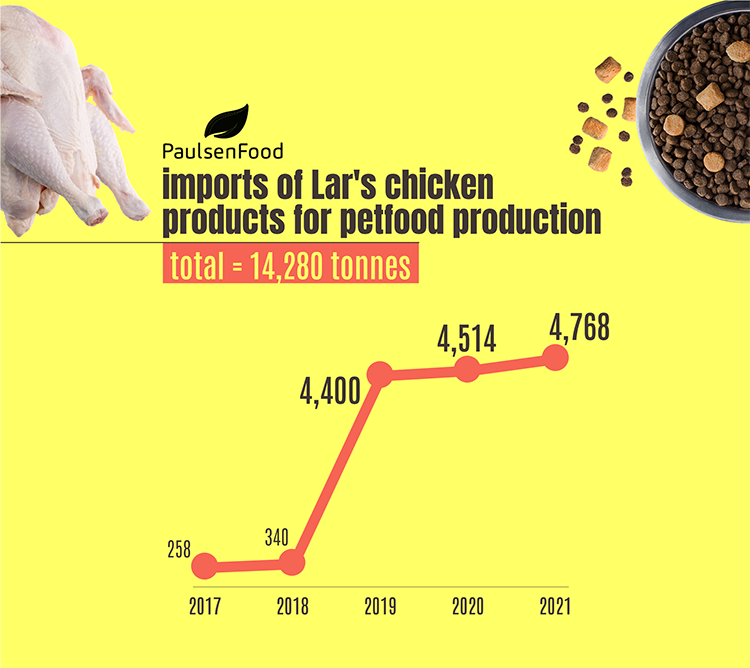

Since 2017 Westbridge has been owned by Thai food giant Charoen Pokphand Foods (CPF), which went on a shopping spree in Europe that year and also acquired the German firm Paulsen Food. Paulsen is an even more important buyer of Lar chicken, accounting for nearly half of the Brazilian exporter's sales to the EU and UK.99 Between 2017 and 2021, Paulsen's imports from Lar to Germany increased more than five-fold.

Before being acquired by CPF, Paulsen belonged to the Heristo AG group100, which also owns major pet food manufacturers Saturn Petcare and Animonda Petcare. In the 2017-2021 period, Paulsen bought over 14,000 tonnes of chicken products for the manufacture of pet food from Lar, being the latter's only major customer for this type of product in the EU. Paulsen's purchases of this type of product from Lar in 2021 were 17 times higher than in 2017.

Through their correspondence with Earthsight, Animonda's and Saturn's supply chain links to Paulsen were confirmed.101

Saturn Petcare sells pet food to some of the largest retailers in Germany, including Aldi Nord, Aldi Süd, Lidl, dm-drogerie markt, Edeka, Netto Marken-Discount, Rewe Markt, and Rossmann. These retailers sell Saturn Petcare products under their own brand names (see table below).102 Animonda, on the other hand, supplies its own pet food brand to several retailers in Europe, including Fressnapf and online retailers Zooplus, Vetsend and Medpets.103

Onlinepets (which owns Vetsend and Medpets) did not reply to Earthsight's requests for comment. Edeka, Netto Marken-Discount, Lidl, Aldi Süd, Aldi Nord, dm-drogerie markt, Fressnapf, Rossmann, Zooplus, Saturn Petcare and Animonda emphasised their efforts to monitor and vet suppliers based on, among other things, environmental, social and human rights criteria (see their full responses here).

Fressnapf, Rossmann and Saturn Petcare mentioned their adherence to the International Labour Organization's human rights standards, while Lidl, Netto Marken-Discount and Edeka highlighted codes of conduct based on the Accountability Framework Initiative. Animonda, Rossmann, Saturn Petcare and Zooplus said they would terminate relationships with suppliers found to be linked to indigenous rights violations. Fressnapf and Rossmann stated they will further investigate the issues highlighted in this report. Animonda, Saturn Petcare and Zooplus pointed to Lar's BRC and Smeta certifications to indicate their careful approach when selecting suppliers. Several companies also said they fully support the implementation of ambitious EU-level regulations to stop commodities linked to environmental and human rights abuses from entering the common market.

Animonda pet food on sale in Germany, May 2022 © Earthsight

Animonda pet food on sale in Germany, May 2022 © Earthsight

Animonda pet food on sale in Germany, May 2022 © Earthsight

Animonda pet food on sale in Germany, May 2022 © Earthsight

Rewe Markt, Rossmann and Saturn Petcare stated that the soybeans Lar buys from Brasília do Sul are not used in the production of animal feed and, as such, are not linked to their pet food products. Rossmann stated that, according to Lar, the soy used in its animal feed comes from Paraguay. dm-drogerie markt said they "do not use any raw materials that originate from Brasília do Sul" for their Dein Bestes brand.

The companies did not provide any evidence to substantiate these statements, which appear to contradict Lar's public declarations linking its Caarapó soy processing unit to meat production. Their responses seem to indicate they are relying on Lar's assurances alone.

Neither Lar itself nor Paulsen ever replied to Earthsight's repeated requests for comment.

None of the companies in Germany denied doing business – directly or indirectly – with Lar. These firms do not seem to have found reason for concern in sourcing chicken products from an exporter with clear links to a farm implicated in the violent suppression of indigenous rights. Based on their responses to this report, Lar's links to Brasília do Sul did not raise red flags in their monitoring efforts. Lar's BRC and Smeta certifications mentioned by some companies are schemes meant to verify food safety and workers' conditions, not compliance with indigenous rights.

Not a single manufacturer or retailer mentioned in this report was able to convincingly explain how they are able to stop chicken products linked to indigenous rights violations from entering their supply chains. Their responses indicate that Brasília do Sul’s links to Lar – or, for that matter, Lar's links to Westbridge and Paulsen – were first brought to their attention by Earthsight. As to the UK retailers' denials that their Westbridge chicken is linked to South America, Brazil or Lar, it's far from clear whether this is the result of a policy decision or otherwise. Also unclear is whether the companies that have stated a willingness to terminate relationships with suppliers found to be linked to indigenous rights violations will do so in relation to Lar.

Lar allegedly reported to Rossmann that the soy it uses to feed its chicken comes from Paraguay. This raises further questions. As the history of the Jacintho family itself shows, agribusiness in Paraguay has its own track record of environmental and human rights abuses, including in soy production.104 Are Paulsen, Saturn, Animonda and their retail customers now looking into this alleged Paraguayan origin of the soy for animal feed and its potential links to illegalities in the country? Nothing in their statements indicates they already knew about this apparent Paraguayan connection. Is this something they are going to investigate?

What's more, the soy industry is subject to change. It's been recently reported that, due to droughts, Paraguay's soybean production will drop by over two-thirds this year compared to the 2020-21 harvest. The country's soy exports will be significantly affected.105 If Lar's allegations about the source of its soy for animal feed are true, are businesses in Europe prepared to identify potential shifts in the company's sourcing patterns?

As some firms stated support for upcoming EU regulations banning commodities linked to deforestation or human rights violations from the common market, it is important to raise some final questions. Once such regulations are in place, what kind of 'due diligence' practices are they going to implement to guarantee compliance? Will they be entirely dependent on suppliers' assurances? Perhaps more importantly, will enforcement authorities take blanket denials of links to problematic sources at face value, or will they demand convincing evidence? These are critical issues for the success of new legislation currently under debate in Europe, the UK and the US, to which we'll return shortly.

Brasília do Sul's soy is linked to European consumers in other ways too. Coamo Agroindustrial Cooperativa, a major grain and vegetable oil producer in southern Brazil with over 29,000 members106, has silos in Caarapó, the same municipality in Mato Grosso do Sul where Lar operates a soy processor. According to our field investigation, these silos receive soy from Brasília do Sul.

Between 2017 and 2021, Coamo exported 3.9 million tonnes of soy oilcake to the EU and UK, where its main markets are Germany, accounting for about half of its exports to the region, and the Netherlands (36 per cent).107 Soy oilcake is used in the production of livestock feed for poultry, pigs and cattle.

Coamo's largest customer in Europe is its own subsidiary Coamo International AVV, a company registered in the tax haven of Aruba and cited in the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists' Offshore Leaks Database, which is part of the Pandora Papers, Paradise Papers, Bahamas Leaks, Panama Papers and Offshore Leaks investigations.108 Coamo also exports oilcake to other large global traders in Europe.

The company was implicated in what has been publicly referred to as the 2016 "Massacre of Caarapó", a violent attack against the Guarani Kaiowá community of Tey'i Kue in Mato Grosso do Sul perpetrated by over 70 gunmen linked to local farmers.109 The convoy of trucks that attacked the community reportedly left the Coamo facility in Caarapó after spending nearly two hours there. The episode, infamous for its extraordinary levels of brutality and cruelty, left indigenous health worker Clodiode Aquileu Rodrigues de Souza dead and several others injured.110, 111 There is no evidence that Coamo was involved in the attacks. Coamo did not reply to Earthsight's requests for comment.

The Jacintho family members' ranches implicated in reported indigenous rights violations and illegal deforestation in Paraguay have also been linked to global markets. Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco revealed the links between Yaguareté Porã, Bastos Ferraz's farm at PNCAT, and leather used by BMW and Jaguar Land Rover, as well as other giant car manufacturers.112

Firms' inability or unwillingness to cut ties with suppliers linked to reports of egregious human rights abuses turns consumers into unwitting instruments of injustice. While some of the businesses highlighted above have indigenous rights or human rights policies in place, none has done enough to ensure their supply chains are not implicated in the ongoing destitution of an indigenous community. Industry voluntary certification schemes have fallen short of the necessary levels of monitoring and accountability.113 For these reasons, campaigners have for years demanded government intervention. We are presently closer than ever to achieving that. But some obstacles remain.

Brasília do Sul's soy is also linked to European consumers through Coamo Agroindustrial Cooperativa, a major grain and vegetable oil producer in southern Brazil with over 29,000 members © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Brasília do Sul's soy is also linked to European consumers through Coamo Agroindustrial Cooperativa, a major grain and vegetable oil producer in southern Brazil with over 29,000 members © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

7. Keeping Bad Ag at bay

The role consumer markets play in global deforestation has been highlighted on several occasions.114 Their high-volume imports of soy, palm oil, beef, leather, cocoa and other agri-commodities create market incentives for agribusiness expansion into producer countries' forested areas. They are by far the largest driver of global forest loss, which is in turn responsible for some 12 per cent of annual climate emissions.115

Equally important are the impacts this deforestation and other associated practices – land grabbing, corruption, violence – have on local communities.116

After years of campaigning, governments in some of the largest consumer markets – including the EU, UK and US – have finally begun to debate legally binding regulations to limit their countries' contribution to both forest loss and human rights abuses abroad.

With regard to forests, the EU Commission's proposal for a regulation, currently under consideration by the European Parliament and Council, is possibly the most ambitious. Not only does it aim to ban commodities and derived products linked to illegal deforestation, but it also attempts to address sustainability concerns by demanding that supply chains be deforestation free.117

While a zero-deforestation demand for supply chains linked to Brasília do Sul is less relevant – as the area was mostly cleared of its native vegetation several decades ago118 – the businesses using the farm's soy should be accountable for their role in propping up a farm implicated in ongoing indigenous rights violations. This is where the EU's proposal becomes more contentious.

As it stands, the regulation would only consider national law as a basis for human rights monitoring in supply chains. This falls short of demanding that businesses take into account international treaties and customary law in assessing their exposure to communities' rights violations. This is important because not all producer countries have the necessary national legal protections in place to guarantee indigenous and other traditional peoples' rights over their ancestral lands in line with international law and standards.119, 120

Brasília do Sul is in a country with such laws.121 But successive Brazilian governments have failed to implement them. More than that, Brazil's current government is openly against such laws and has attempted to undermine them.122 The EU regulation could therefore offer a check to European supply chains profiting from Brasília do Sul's soy.123 But again, efforts to hold companies to account under the regulation would run against another limitation.

As we have seen, Brasília do Sul's soy enters supply chains linked to European markets through chicken exports. While soy is covered by the upcoming EU regulation, chicken is not.124 This means chicken importers will not be under the same monitoring obligations. Campaigners have called on the EU to expand the scope of products covered by the regulation, both by adding commodities such as poultry to the list, as well as by including all products that contain, have been fed with or have been made using any of the covered commodities.125

If the Guarani Kaiowá and other peoples are to have opportunities to hold businesses profiting from their lands to account, it will be crucial that upcoming regulations – in Europe and elsewhere – include provisions to such effect. Right now, all of them fall short in this regard.126

Dissuasive penalties for companies that flout the rules will be key. A crucial enforcement element would be a requirement for authorities to publish lists of non-compliant companies. Such a list is readily enforceable and serves as a powerful deterrent regardless of the financial penalty likely to be applied. Such a clause was included in an earlier draft of the EU Commission's proposal but was later dropped. It must be reinstated in the final regulation.

The UK Environment Act, approved by Parliament last year, is less ambitious than its EU counterpart as it is focused solely on legality and ignores sustainability concerns. Of more immediate effect for the case highlighted here is the fact that it does not directly address human rights violations. This is a glaring shortcoming for a regulation that should aim to not only limit Britain's role in forest loss overseas but also the human impacts of agribusiness expansion.127

Recently the UK Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) ran a public consultation to inform secondary legislation that will determine the commodities to be covered, types of businesses to be subjected to the law, and how it will be enforced. Signs are not encouraging. The way the consultation is framed suggests authorities are favouring an extremely limited list of commodities to be included and exemption to all but the largest businesses. Numerous loopholes seem to be under consideration.128

Ambitious secondary legislation could ensure the Environment Act has a meaningful impact. It must therefore cover a broad range of commodities from the outset, ensure effective enforcement – not least by way of a public list of offending actors – and provide access to justice for affected communities.

Apart from forest-specific legislation, wider supply chain ethics laws are under debate. One example is the EU's Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive, an initial proposal of which was published in February.129 Civil society has already raised concerns over the proposal's restricted scope on company size and loopholes on companies' liability.130 As with regulations on forest-risk commodities, these broader laws will need to be well designed if they are to prevent consumers from being associated with abuses such as the ones highlighted here. The devil is in the detail.

Bold consumer market legislation will be crucial in the global fight against deforestation, climate change and human rights abuses. But on its own it won't be enough. The case of Takuara also reveals deeper structural issues that need to be tackled with equal resolve by a range of stakeholders, including governments in both producer and consumer countries. The plight of the Guarani Kaiowá contains lessons that are yet to be learned.

8. Dead letter

This is not a story about recent deforestation. The Brasília do Sul farm is also only a fairly small dot on a much, much larger landscape of devastation and theft which spans Brazil. But while Takuara was denuded of most of its forest cover decades ago – especially after da Silva Filho acquired the land – the profits from Brasília do Sul have helped the Jacintho family cement and grow its political influence. In doing so, the family has increased its control of land in Brazil and Paraguay, in direct conflict with the ancestral land rights of local communities.

In this sense, Brasília do Sul is just a part of a bigger story regarding the Jacintho family's wider – and continuing – destruction of lands and forests that should rightly belong to indigenous people. It is also emblematic of the underlying causes behind Latin America's wider deforestation calamity: the lack of respect for the rights of indigenous and other traditional communities, the undue and poisonous political influence of the agribusiness lobby, and the violence and impunity it breeds.

The murder of Marcos Veron, the encroachment of protected Ayoreo Totobiegosode lands in Paraguay, and the persistent destitution of so many forest communities speak volumes about states' historical failure to fulfil their legal obligations and correct the wrongs of the past.

When it comes to Funai's efforts to clarify Takuara's status as an indigenous land, Jacintho Honório da Silva Filho adopted an intimidating attitude from the start.131

The Jacintho family has not been shy about using the justice system to obstruct government efforts to demarcate Takuara. Faced with overwhelming evidence to the contrary, their lawyers have flatly rejected the notion of any historical indigenous presence in the area and instead accused Funai of being captured by ideological interests.132, 133

Indigenous leaders emphasise the odds communities face in Brazil's justice system.134 The last 23 years of litigation on Takuara illustrate this. In 1999 it took a local judge less than 24 hours to rule for the Guarani Kaiowá's eviction, without even having the authority to do so.135 Contrast this with the impunity enjoyed by those accused of Marcos Veron's murder for the last 19 years.

Federal prosecutor Delfino is categorical: "We have to understand that racism in Brazil is structural. If we had the opposite situation where an indigenous person had killed a landowner, this case would have concluded a long time ago."

"Jail in Brazil has always been for black people, prostitutes, and the poor. The release of Rodriguinho reflects this logic," he added.136

Antônio Eduardo Cerqueira de Oliveira, Executive Secretary of the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI), one of the largest indigenous rights organisations in Brazil, has seen several cases of judges cancelling demarcation processes. "There's considerable legal insecurity for indigenous people as a result of political pressures," he says.

Indigenous people have faced obstacles all the way up to the Supreme Court. The court's 2010 decision to suspend Takuara's demarcation dealt a blow to the community. In her decision, Justice Lúcia relied on the marco temporal precedent set by her peers (see above).

Marco temporal has been used by the agribusiness lobby to block demarcations.137, 138 Indigenous organisations have decried it as a cynical ploy that violates the Constitution and its intent to protect communities long hurt by state policies. In June this year the Supreme Court is expected to hold a hearing on the issue with the aim to put it to rest.139 If the ruling sides with agribusiness, it could become much harder for communities to ever regain access to their lands.

Tonico Benites, a Guarani Kaiowá leader and anthropologist from the Sassoró indigenous land in Mato Grosso do Sul, believes few people stand to lose more than his own.140 "I think the marco temporal was created to hurt the Guarani Kaiowá in particular because everyone knows we were evicted [from our lands] before 1988," he argues.

With a justice system stacked against them, indigenous peoples have for years tried to pressure the federal government to demarcate their lands as stipulated in the Constitution. But here too, the obstacles are daunting.

Jorge Eremites de Oliveira, historian and anthropologist at the Federal University of Pelotas, says that "all governments, some more others less, have been anti-indigenous. But Bolsonaro's government is the worst of the worst. What we have now is the radicalisation of a genocidal war."

Bolsonaro has publicly declared his opposition to indigenous land rights and promised not to demarcate one centimetre of land to indigenous communities.141 Under his direction, Funai – now stacked with his allies – has adopted perverse anti-indigenous stances.142, 143 Last year the Articulation of Indigenous Peoples from Brazil (APIB) filed a statement to the International Criminal Court asking its prosecutors to "examine the crimes perpetrated against indigenous peoples by President Jair Bolsonaro since the beginning of his term." The Guarani Kaiowá were highlighted in the report as one of the most affected groups.144, 145

For Cerqueira de Oliveira, an anti-indigenous decision over the marco temporal would be a great boost to Bolsonaro's administration: "The government is counting on this ruling to proceed with the so-called 'final solution' for indigenous people, which is the complete appropriation of their lands by private capital, especially agribusiness."

In Mato Grosso do Sul, the state government has also sided with landowners. During the litigation over Takuara, it petitioned courts to be included as a party to the case in order to argue against demarcation.146

"The crux of the issue is the State, which created this whole situation in the first place by selling indigenous lands as if they were vacant. Now you have agribusiness pitted against indigenous people and the State is absent," Stefanes argues.

The federal judge who ordered the Guarani Kaiowá's eviction from Takuara in 2001 stressed that courts are put in an impossible position. In his ruling, he argued he could not ignore the Jacintho family's legal ownership of Brasília do Sul. On the other hand, he acknowledged that courts cannot have the final say on indigenous land disputes, which often arise and endure as the result of political decisions.147

On the issue of legal ownership, though, Cerqueira de Oliveira thinks judges are getting it wrong: "The Constitution is clear. As soon as the land is recognised as traditional indigenous land based on a Funai study, all [private] titles over it are to be considered void."

The Jacintho family enjoys a life of luxury and glamour, whereas indigenous communities in Mato Grosso do Sul struggle. While visiting the region for this report, our team came upon indigenous people collecting food, clothes and other items at a landfill. Maristela Aquino, a schoolteacher for Guarani Kaiowá children, was at the site. "The Kaiowá feel guilty, embarrassed, inferior and despised, but this situation is not their fault," she said. "This comes from a historical process of discrimination, displacement, confinement to the reservations, and government failure to return to them what's theirs."

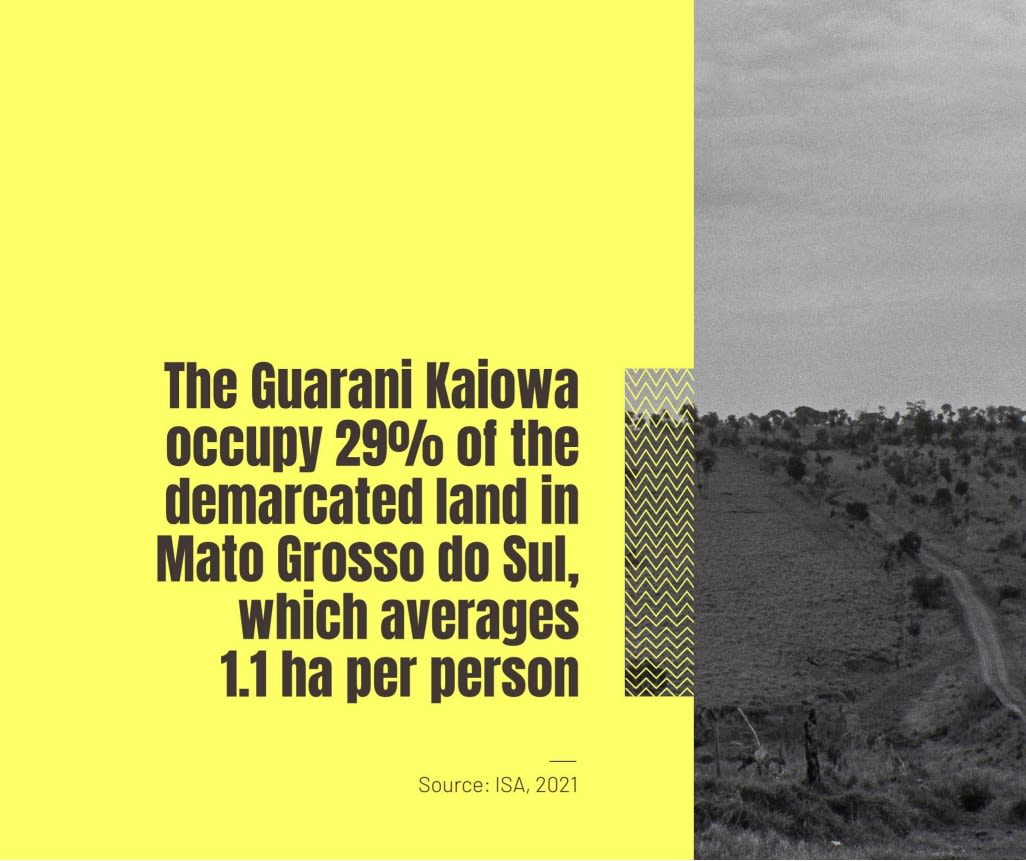

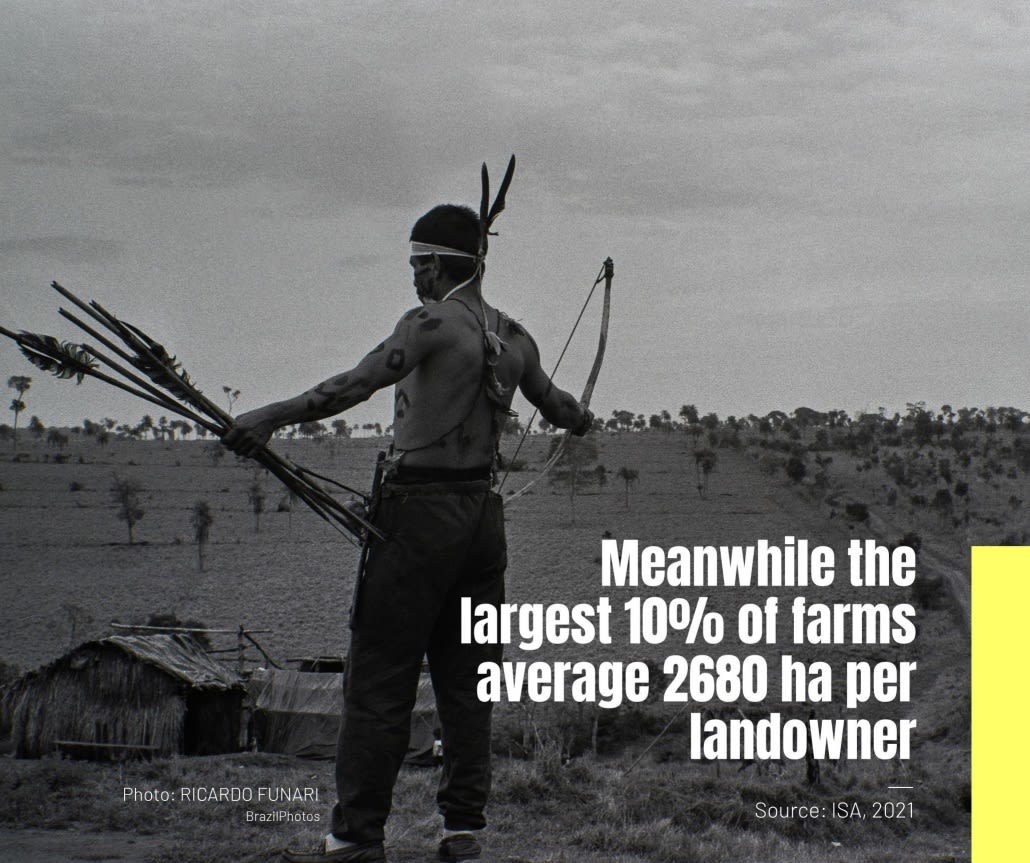

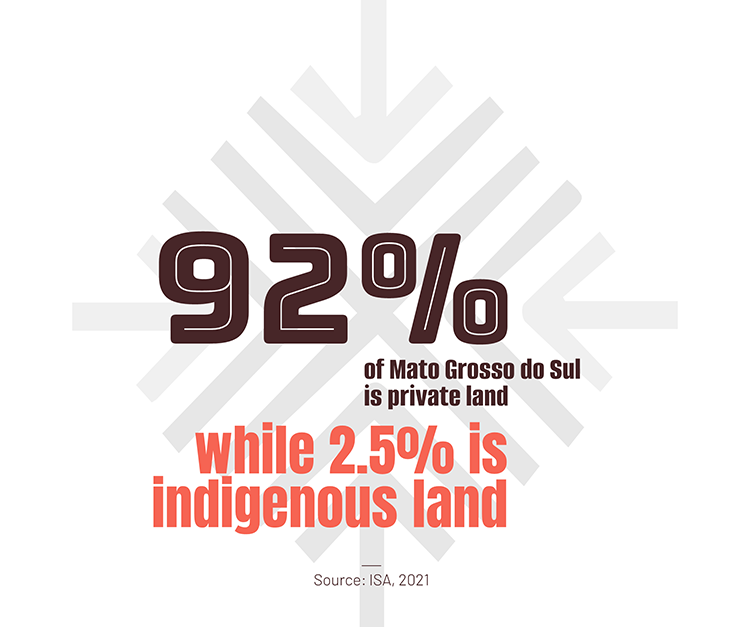

Indigenous communities in Mato Grosso do Sul currently live in areas that are a fraction of their traditional lands.148 This prevents them from living according to their customs and traditions, which include hunting, fishing, gathering medicinal plants, and visiting the sites that have a significance to their cosmology and collective memory.

"Article 231 of the Constitution about guaranteeing the cultural and physical reproduction of indigenous peoples is ignored," Eremites de Oliveira says.149

Even if the communities were to reoccupy larger areas, their troubles wouldn't be over. "The rivers, forests, wildlife are all dying," Valdelice notes in reference to the heavy use of agrichemicals by landowners and the near total absence of native forests in the area.

Indigenous leader Erileide Domingues, of the Guyraroká community near Takuara, agrees. "They spray their hatred over our communities" in the form of pesticides.150 Reported cases of aerial spraying of agrichemicals in Mato Grosso do Sul were called "chemical aggressions" by prosecutor Delfino.151

Indigenous leader Erileide Domingues, of the Guyraroká community near Takuara © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Indigenous leader Erileide Domingues, of the Guyraroká community near Takuara © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

9. Return of the guardians

Eliel Benites, a Guarani Kaiowá leader and academic from the Te'ýikuê village in Mato Grosso do Sul © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Eliel Benites, a Guarani Kaiowá leader and academic from the Te'ýikuê village in Mato Grosso do Sul © Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Guarani Kaiowá child seen during a protest to defend indigenous land, outside Brazil's Supreme Federal Court in Brasilia, Brazil, June 2019 © REUTERS / Adriano Machado / Alamy Stock Photo

Guarani Kaiowá child seen during a protest to defend indigenous land, outside Brazil's Supreme Federal Court in Brasilia, Brazil, June 2019 © REUTERS / Adriano Machado / Alamy Stock Photo

"The Guarani Kaiowá's resistance is unique in the world. Their children, women and men are very strong and very clear about their rights."

The Guarani Kaiowá have a special relationship with the land. The term Tekohá came up often during interviews. Eliel Benites, a Guarani Kaiowá leader and academic from the Te'ýikuê village in Mato Grosso do Sul, calls the Tekohá the "sacred village".152 It can be understood as the place where the community can live according to its beliefs, cosmology and traditions, with important markers of ancestry and collective memory.

"The forests, rivers, plants and the wind have spiritual guardians. Our aim is to restore the health of the land to allow us to reconnect with this divinity and give meaning to our lives," Benites says.

Benites is aware of the challenges they face in a deforested landscape. "Amid this destruction the guardians withdraw, and the land becomes naked, with an open wound. If we can reforest the land the guardians can return," he adds.

The loss of their lands has meant the loss of a sense of place in the world for many Kaiowá. Historian Rosely Stefanes, who has seen first-hand cases of suicide among Guarani Kaiowá youth, stresses the lack of perspectives affecting them. "They are dehumanised because [outside their communities] they are expected to behave as non-indigenous and this generates deep internal conflicts in young people," she says.153

Several Guarani Kaiowá leaders interviewed by our team mentioned issues of domestic violence, alcoholism, drug abuse, suicides, and a general sense of despair among many young indigenous people.

Some remember fondly the attempts to reoccupy their lands, even faced with enormous risk. "We prayed for several days to ward off bad spirits from our path. It was so beautiful, we felt happy. It was as if we were returning to our mother's lap," recounts Anastácio Peralta, a Guarani Kaiowá leader from the village of Panambizinho, about preparations for a retomada several years ago.154

Farmers have learned they can hit indigenous communities where it hurts. "Twenty prayer houses have been set on fire since 2021. They realised they must attack this source of mystical-religious strength so [indigenous people] lose this cultural force," says Cerqueira de Oliveira, the head of CIMI.155

Despite their current predicament, the Guarani Kaiowá do not see themselves as helpless victims. Those who have spent time with them often highlight their capacity for resilience and hope. "The Guarani Kaiowá always have a smile on their faces," says Maristela Aquino, the schoolteacher we met at the landfill.

Valdelice embodies this spirit and calls on others to join their struggle. "The aim of Brazil's rulers is the extermination of our people. My message to you watching our situation in Mato Grosso do Sul and in Brazil is that you rise up with us."

- Click here to read the companies' full responses to Earthsight

May 2022

Credits

Research: Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Footage: Earthsight / De Olho nos Ruralistas

Data visualisation and graphic design: @FlavitoReis

Murder of Marcos Veron illustrations: Matt Hall