Paraguay's Looted Lands

How war, trade and dictatorship created the world’s worst deforestation crisis

Grand Theft Chaco revealed that European car firms are sourcing leather from illegally deforested land in Paraguay. Not only are these clearances fuelling the climate crisis and destroying native biodiversity, they are also wrecking the forest home of one of the world’s last isolated indigenous tribes.

Indigenous communities, environmentalists, and state whistleblowers have all fought back against this illegal deforestation. In doing so, they’ve confronted formidable vested interests: power structures with deep roots in Paraguayan history.

Here, Earthsight examines how a century and a half of war, trade and dictatorship have turned Paraguay into the world’s number one deforestation hotspot.

“The history of Paraguay is one of struggle over land”

Luis Rojas, economist and author of Yvy Jara: The Owners of the Land in Paraguay

In the late nineteenth century, Paraguay suffered a military calamity without parallel in modern history. In 1864, regional tensions sparked into war, pitching Paraguay against a triple alliance of Brazil, Argentina and Uruguay. Paraguay faced overwhelming odds and, despite a string of early victories, by 1867 the Paraguayan army had been annihilated. But its leader, President Solano López, refused to surrender. He conscripted slaves and children to continue the fight, promoting his 14-year-old son to the rank of Colonel.

President Lopez was finally shot dead in 1870 as he fled into the dense subtropical forests of eastern Paraguay. His wife, an Irish adventuress named Eliza Lynch, buried him and their colonel son in the red dirt, watched by Brazilian soldiers.

By the time it reached this grisly denouement, the war had wiped out two-thirds of Paraguay’s population, including 90 per cent of its men. The subsequent peace treaty cost the country a third of its territory and saddled it with enormous debts. To pay off these debts, the government sold swathes of public assets to foreign companies.

Its principal asset was land. Thirty-two firms snapped up more than 16 million hectares, 40 per cent of Paraguay’s territory. A single Spanish businessman, Carlos Casado, acquired seven million hectares - a property larger than the Republic of Ireland.

This mass sell-off set the mould for Paraguay’s economy as it moved into the twentieth century. It transformed Paraguay into a provider of cheap raw materials for the global market. It established land as the basis of the nation’s wealth. And it transferred ownership of this land into the hands of a tiny elite.

Luis Rojas

Luis Rojas

Today, Paraguay has the most unequal land distribution of any country in the world. Just 12,000 people own 90 per cent of Paraguayan land; the remaining 10 per cent is split between more than 280,000 small- and medium-sized producers. Beyond that lies a destitute hinterland of 300,000 small-scale farming families without access to any land at all. This generates a gini coefficient of 0.93, far higher than anywhere else even in the notoriously unequal region of Latin America: Brazil, Colombia and Peru come closest, all with a score of 0.86.

“The great war of the triple alliance transformed Paraguay’s economic model. Previously, Paraguay had a diversified production base with an emphasis on the internal market and strong participation of the state. This changed radically after the war. They privatised state resources, principally land, and as a result politics, governance and laws all changed too. Paraguay became first and foremost a provider of primary materials for the international market”

Two-thirds of Paraguay's population lost their lives during the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Creative Commons

Two-thirds of Paraguay's population lost their lives during the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Creative Commons

Brazilian battleships depicted in the River Paraguay near Humaita in 1868, during the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Shutterstock

Brazilian battleships depicted in the River Paraguay near Humaita in 1868, during the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Shutterstock

A banknote from 2004 adorned with the image of President Solano Lopez, Paraguay's leader in the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Shutterstock

A banknote from 2004 adorned with the image of President Solano Lopez, Paraguay's leader in the Triple Alliance War. Credit: Shutterstock

Today, Paraguay has the most unequal land distribution of any country in the world. Credit: Earthsight

Today, Paraguay has the most unequal land distribution of any country in the world. Credit: Earthsight

The ill-gotten

gains

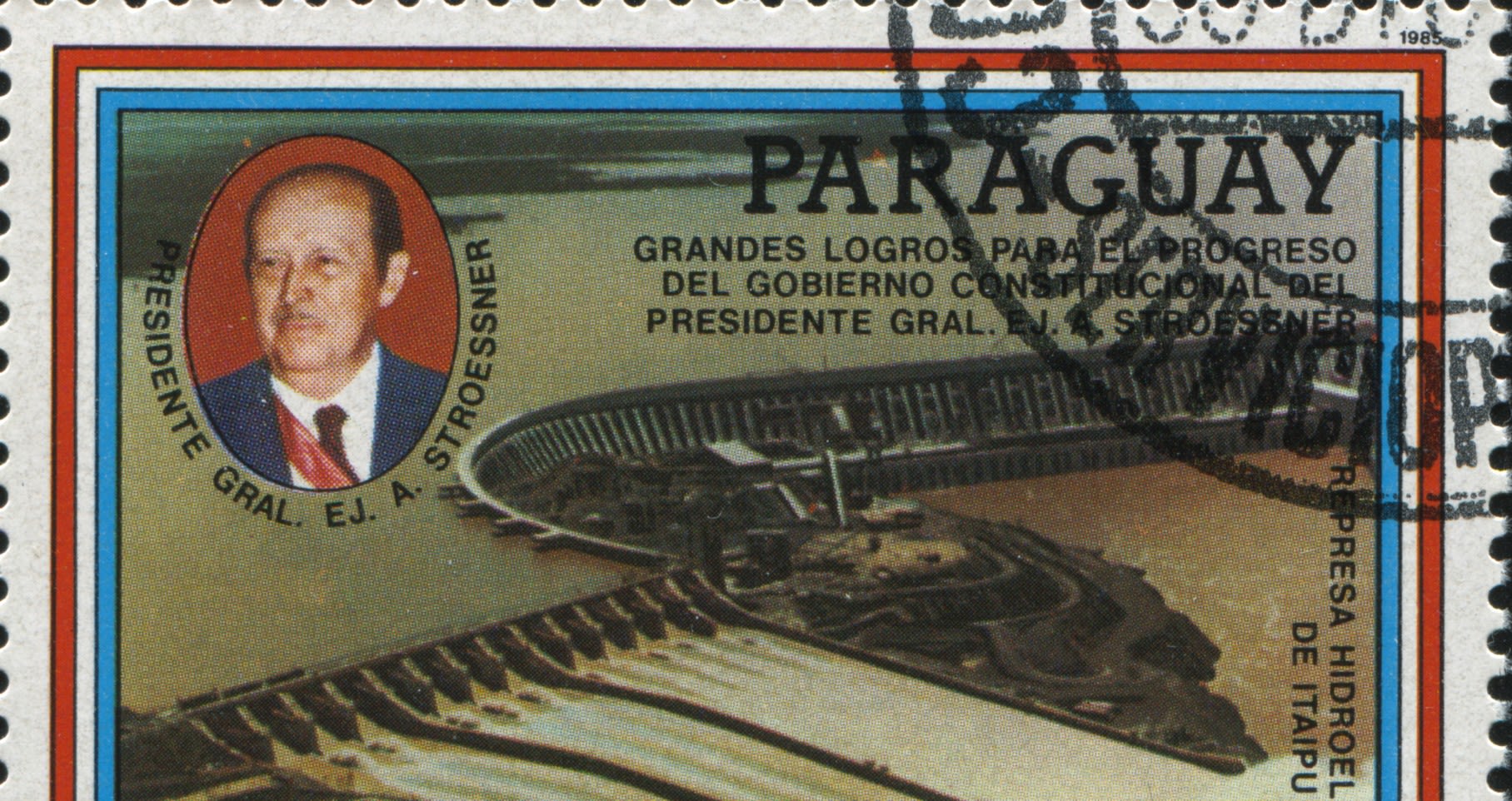

General Alfredo Stroessner oversaw a brutal regime during his 35-year reign as President of Paraguay. Credit: Creative Commons

General Alfredo Stroessner oversaw a brutal regime during his 35-year reign as President of Paraguay. Credit: Creative Commons

A man holds a newspaper during a event marking the 23rd anniversary of the fall of Stroessner in Asuncion, 2012. The newspaper reads "Dictatorship never again". Credit: Alamy

A man holds a newspaper during a event marking the 23rd anniversary of the fall of Stroessner in Asuncion, 2012. The newspaper reads "Dictatorship never again". Credit: Alamy

Two men pay their respects to those killed in Curuguaty at a makeshift altar erected by relatives at the site of the massacre. Credit: Alamy

Two men pay their respects to those killed in Curuguaty at a makeshift altar erected by relatives at the site of the massacre. Credit: Alamy

Crowds march in Asuncion to denounce the ousting of President Lugo and the Curuguaty massacre, 2012. Credit: Creative Commons

Crowds march in Asuncion to denounce the ousting of President Lugo and the Curuguaty massacre, 2012. Credit: Creative Commons

A woman prays for Lugo outside the National Congress before the start of his impeachment trial, 2012. Credit: Alamy

A woman prays for Lugo outside the National Congress before the start of his impeachment trial, 2012. Credit: Alamy

While the war set the mould, later events intensified the stratification of wealth and power in Paraguay. A century after Lopez was killed, bonds between the country’s landowners and its political class were tightened under the rule of General Alfredo Stroessner.

A Cold War dictator, Stroessner came to power in 1954 and stayed there for 35 years. He maintained control by forging alliances with the country’s military and political elite, principally members of the establishment Colorado Party. As part of these clientelist networks, Stroessner divided what remained of public land among his allies. Eight million hectares were given away or sold at negligible prices to army generals and Colorado grandees. This land was ostensibly destined for small-scale farmers as part of a programme of agrarian reform, and so has come to be known as las tierras malhabidas - ‘the ill-gotten lands’.

Stroessner was finally forced out in 1989. But Paraguay’s fledgling democracy has made little progress in dismantling the underlying structures tying land ownership to political power. More than 120 campesino leaders have been killed in the struggle for land since Stroessner’s ouster, and hundreds more imprisoned. Concomitantly, the country’s politics have remained dominated by the Colorado Party, which has held power for 68 of the past 72 years.

Luis Rojas

Luis Rojas

The only break in this hegemony began in 2008. In that year’s Presidential elections, a former Bishop named Fernando Lugo won a shock victory on a platform of agrarian reform - promising to redistribute the ill-gotten lands to their rightful owners.

This project came to an abrupt end in 2012. On a cool June day in the soy-growing department of Curuguaty, six police officers and 11 poor farmers were shot dead in the context of a long-running land dispute with a former Colorado Party president. Despite suspicious circumstances around how shooting began, indications of extrajudicial executions, vanishing police helicopter recordings, and the absence of any evidence linking the occupiers’ five rusty shotguns to the dead police, the clash was seized on as a pretext to impeach President Lugo. The move was condemned as a coup by Paraguay’s neighbours, who expelled the country from regional trade body Mercosur.

Less than a year later, the Colorados were back in power. At the helm was Horatio Cartes, one of the country’s richest businessman and owner of vast landholdings acquired in part from General Stroessner. Unsurprisingly, during Cartes’s half-decade in power, no progress was made in recuperating the ill-gotten lands.

“A close alliance has formed between landowners, capitalists, agribusiness owners, and the political parties that manage the state and political institutions”

Vanishing

forests

Such intimacy between political power and land ownership has predictable consequences for the capacity of Paraguay’s institutions to regulate agribusiness. This leaves Paraguay’s forests - rooted in land coveted by soy farmers in the east, and cattle ranchers in the west - highly vulnerable.

Introduced in 1973, Paraguay’s Forestry Law establishes clear requirements of landowners that wish to clear forest on their holdings. They must first gain authorisation from both the environment ministry and Paraguay’s National Forestry Institute. Once this is granted, they must maintain 25 per cent of the natural forest on their land as a “forest reserve”. Fifteen per cent more must be retained as protective strips between 100-hectare bands of deforestation; if water sources are present, further protective strips of tree cover must be conserved to protect them.

But these laws are frequently bypassed. Ezequiel Santagada, head of Paraguay’s independent Environmental Law and Economy Institute (IDEA), recently led a year-long investigation into deforestation in Paraguay’s western Chaco region, which has been experiencing the highest deforestation rates on earth.

Ezequiel Santagada

Ezequiel Santagada

By setting satellite imagery of properties against Paraguay’s forestry law, IDEA compiled irrefutable evidence of illegal deforestation. This painstaking analysis achieved a rare criminal charge against a powerful Chaco landowner.

“What we have detected, with all our analysis, is that a minimum of 20 per cent of the deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco is illegal,” Santagada told Earthsight. “That’s 36,000 or 37,000 hectares of illegal deforestation every year. And there’s not a single person in prison for this.”

Indeed, the Paraguayan authorities have not only failed to enforce the country’s Forestry Law – they have actively sought to undermine it. In 2017, Cartes passed a law permitting landowners to replace parts of their forest reserve with monocultures for commercial use, or to clear the reserve entirely, by purchasing “environmental services certificates.” The move sparked international outrage and was struck down shortly after Cartes left office - but not before he had used it to clear all the forest on his own ranch.

Alberto Yanosky, conservationist and former director of Guyra Paraguay.

Alberto Yanosky, conservationist and former director of Guyra Paraguay.

“Basically, every two years we lose a million hectares of this environment we know as the Gran Chaco”

Entrance to a cattle ranch in an area of the Paraguayan Chaco exposed to intensive deforestation. Credit: Earthsight

Entrance to a cattle ranch in an area of the Paraguayan Chaco exposed to intensive deforestation. Credit: Earthsight

A bulldozer clears forest in the Chaco region, 2019. Credit: Earthsight

A bulldozer clears forest in the Chaco region, 2019. Credit: Earthsight

It is estimated that at least 20 per cent of all land clearances in the Chaco are illegal. Credit: Earthsight

It is estimated that at least 20 per cent of all land clearances in the Chaco are illegal. Credit: Earthsight

Paraguayan leather and Europe: a love affair

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades. Credit: Survival InternationalGAT

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades. Credit: Survival InternationalGAT

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in Paraguay, with beef and leather predominantly produced for export. Credit: Earthsight

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in Paraguay, with beef and leather predominantly produced for export. Credit: Earthsight

Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco report found leather used by BMW and Jaguar Land Rover was linked to illegal deforestation in Paraguay. Credit: Shutterstock

Earthsight's Grand Theft Chaco report found leather used by BMW and Jaguar Land Rover was linked to illegal deforestation in Paraguay. Credit: Shutterstock

An aerial view of the Cencoprod tannery. The firm is Paraguay's largest leather exporter. Credit: Earthsight

An aerial view of the Cencoprod tannery. The firm is Paraguay's largest leather exporter. Credit: Earthsight

Earthsight’s investigation into deforestation in Paraguay focused on the dry forests blanketing the west of the country, which form part of a lowland biome spread across four countries known as the Gran Chaco. In Paraguay, these forests are home to the only indigenous groups living in voluntary isolation anywhere in the Americas outside the Amazon rainforest.

Our analysis found that the forests of the Paraguayan Chaco are disappearing more rapidly than any other forests on earth. Through the past 15 years, an average of 1200 football fields have been destroyed every single day. This forest has been replaced almost universally by cattle ranches, producing beef and leather for export.

Earthsight investigators connected European car firms, including BMW and Jaguar Land Rover, to ranches installed on illegally deforested indigenous land. Indeed, the EU is by far the biggest customer for Paraguayan leather, with Italy alone importing nearly two-thirds of its total exports.

Paraguay’s leather industry also has its origins in the triple alliance war. Remember Carlos Casado, the Spanish businessman who acquired a property the size of the Republic of Ireland? In 1889, while visiting his kingdom for the first time, Casado discovered a hidden treasure trove: a rich source of tannins in the region’s quebracho trees. At a site now named Puerto Casado, he established Paraguay’s first industrial tannery, using European machinery and tannins from the surrounding forest. In just a few years, production jumped from 120 to 4200 tonnes - making it the biggest leather producing factory in the world.

Ezequiel Santagada

Ezequiel Santagada

Times have since changed: synthetic chemicals replaced natural tannins in the tanning process in the 1940s. But Paraguay remains among the world’s biggest leather exporters, thanks to its enormous cattle ranching industry. Indeed, the firm founded by Carlos Casado - today named Carlos Casado SA and owned by Spanish construction giant San Jose - still possesses more than 200,000 hectares of land in the Paraguayan Chaco.

“We need an environment that is healthy, because a desert doesn't produce meat and a desert doesn't produce soya”

The 2020s: deforestation accelerates

Current deforestation rates are alarming enough. But pressure on Paraguay’s forests is only set to increase through the decade ahead. The current President, Mario Abdo Benitez, succeeded Cartes in 2018 and stems from the same soil as his predecessor. His father was General Stroessner’s private secretary and one of the biggest beneficiaries from the dictator’s generosity with public lands.

Benitez is an enthusiastic supporter of plans to direct a new cross-continental highway through the Paraguayan Chaco. Known as the ‘bi-oceanic corridor’, this massive infrastructure project aims to create a direct route between the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans, connecting seaports in Chile and Brazil. The road’s design would integrate “wildlife passes”, proponents say, enabling animals to cross without interrupting traffic.

Currently, roads in the Paraguayan Chaco are managed principally by private landowners, and frequently become impassable during the rainy season. Should the highway project be realised, it will link ranches directly to both Brazil’s vast meatpacking industry and to Chilean ports serving the far east. Benitez has described the highway as “a little Panama Canal” that will spur “a large part” of Paraguay’s population to move to the Chaco. In 2019, his Minister of Public Works announced $2 billion of infrastructure investment to prepare the region for the transformation.

The highway could help Paraguay meet goals laid out in its National Development Plan 2030, which was adopted under Cartes and remains a key policy document today. The plan aims to make Paraguay the world’s fifth biggest beef exporter, which requires the country’s total cattle herd to increase by four million heads. In turn, this requires around four million hectares of Chaco forest to be cleared over the next decade to create space for the necessary pasture - a doubling of the current, vertiginous deforestation rate. The roots of agribusiness’s dominance in Paraguay might reach back a century and a half, but the fight to save the country’s forests is just revving up.

“In Paraguay there is a permanent environmental crime being perpetrated, in terms of deforestation and pollution - and it is the state that permits it”

Paraguay's Mario Abdo Benitez (second right), alongside Argentine President Mauricio Macri, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and Uruguay's Vice President Lucia Topolansky during the 55th Mercosur summit, 2019. Credit: Alamy

Paraguay's Mario Abdo Benitez (second right), alongside Argentine President Mauricio Macri, Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro and Uruguay's Vice President Lucia Topolansky during the 55th Mercosur summit, 2019. Credit: Alamy

Critics say Benitez's infrastructure projects in the Chaco will intensify cattle ranching and worsen deforestation in the region. Credit: Earthsight

Critics say Benitez's infrastructure projects in the Chaco will intensify cattle ranching and worsen deforestation in the region. Credit: Earthsight

Taming

destruction

From Carlos Casado to BMW, the interests that have ultimately fuelled and profited from the theft of Paraguay’s land and the plunder of its natural resources through the last hundred and fifty years have been wealthy foreign companies. And these firms – along with unwitting foreign consumers - will continue to ‘use and abuse’ Paraguay unless urgent action is taken by governments abroad.

As it stands, things could be about to get much worse. A Free Trade Agreement (FTA) negotiated between the EU and South American trading bloc Mercosur is set to eliminate import duties for thousands of tonnes of Paraguayan beef and leather - supercharging demand for the very commodities that lie behind the bulldozing of Paraguay’s forests.

There are also efforts to stem this tide of destruction, however. The European Commission is committed to introducing legislation this year to tackle the EU’s outsized role in fuelling global deforestation rates. A strong blueprint for these laws was laid down last October, when – following a debate at which Earthsight’s Grand Theft Chaco report was specifically cited - the European parliament adopted a landmark report calling for mandatory rules requiring all companies on the European single market to check, mitigate and prevent the risk of deforestation in their supply chains. These rules should also apply to financial institutions, the report specified, and they should protect forest communities by requiring businesses to operate only where they have Free, Prior and Informed Consent (FPIC).

Meanwhile, the UK is also set to introduce legislation later this year prohibiting firms from using commodities sourced from illegally cleared land. However, the UK’s proposals are weaker than the EU’s, as they apply solely to illegal deforestation – potentially opening a loophole allowing companies to be complicit in forest destruction if it is allowed under local laws.

Today, Earthsight joined @fapi_paraguay, @Fern_NGO, @ForestPeoplesP, @amotocodie, @anna_cavazzini, @Survival & OPIT in urging the Paraguay government to investigate illegal deforestation & indigenous rights abuses in the Chaco.

— Earthsight (@earthsight) January 28, 2021

Action must be taken now!👊https://t.co/mFpCirxoLM

Pressure therefore needs to be maintained on the European Commission to implement the recommendations adopted by the European Parliament, and on the UK government to strengthen its proposals. Simultaneously, the Paraguayan government needs to take action, too, if it is to stand any chance of meeting its international commitments on climate change. Punishing those responsible for the particularly egregious cases Earthsight connected to European carmakers – involving the illegal destruction of forest inhabited by one of the world’s last isolated tribes – would be a good place to start, as a joint letter to the Paraguayan authorities from a coalition of NGOs and indigenous rights organisations recently argued.

It is only by taking decisive actions such as these that we can tame the forces driving environmental degradation in Paraguay, and allow the country’s forests – and all that rely on them – to thrive.