The last refuge

Defending the ancestral forests of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode

- The Ayoreo have fought a decades-long struggle to preserve their ancestral lands and way of life against farmers, missionaries and the incapacity of the Paraguayan state to uphold its commitment to protect their territory.

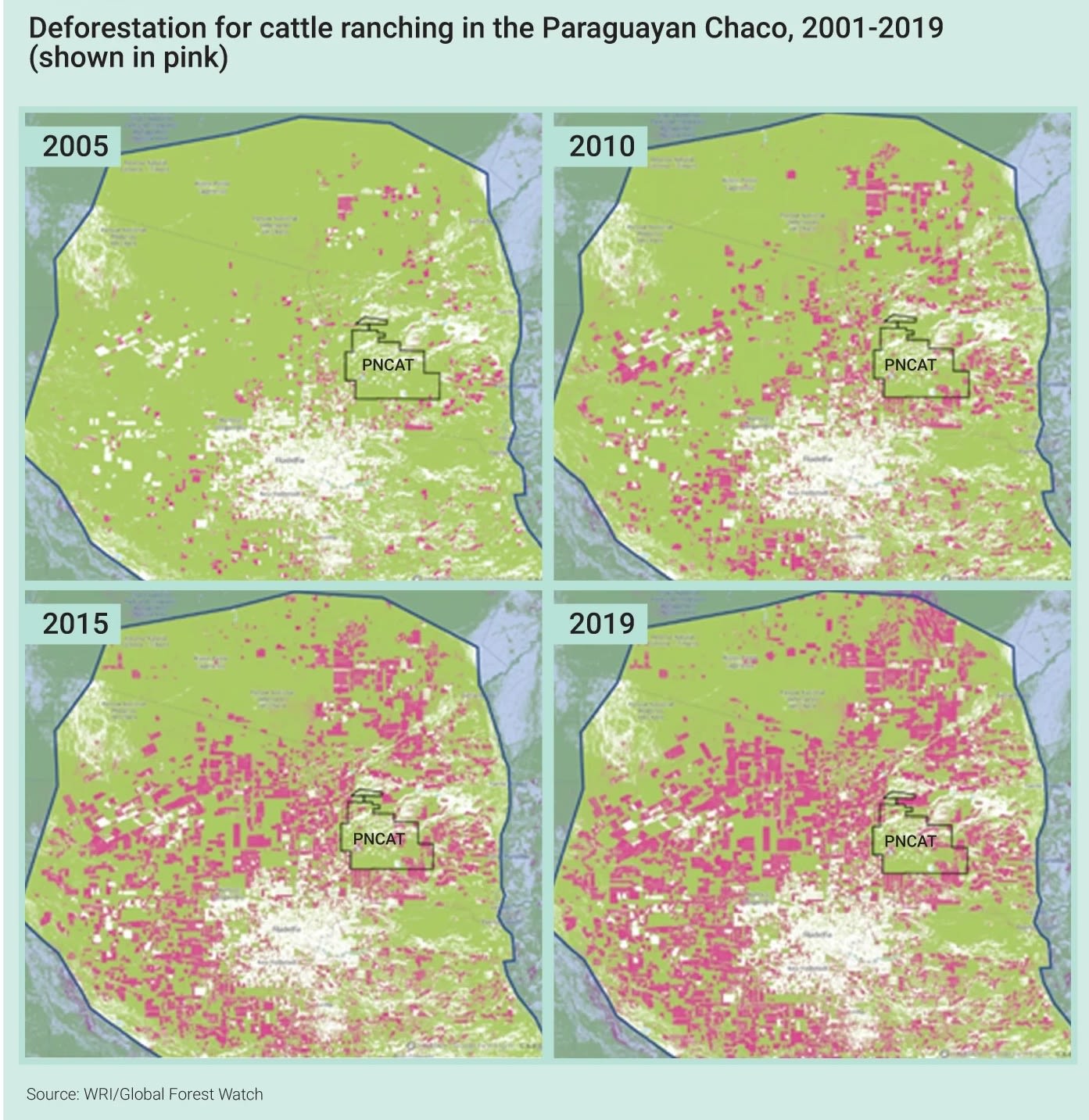

- Their home, the Gran Chaco, is in the midst of a deforestation crisis driven by cattle ranching. The lowland plateau is losing forest cover faster than anywhere else on earth.

- Last year Earthsight exposed the links between the destruction of Ayoreo lands to some of the world’s largest car manufacturers through international leather supply chains. Paraguayan authorities have failed to investigate the evidence of illegalities provided by Earthsight, even after a European MEP and a group of civil society organisations joined us in a public call for action.

- In the last piece from our Grand Theft Chaco series, we chart the Ayoreo's long struggle against the outside forces threatening their very existence and provide an update on developments in Paraguay since our report was published.

Tagüide Picanerai is wearing a camo-coloured t-shirt that blends with the thorn-studded trees and dusty undergrowth behind his back. At his feet, beside a charred circle of soil, lies a handful of bones. These are the postprandial remains of a Chaco tortoise, considered a delicacy by the Ayoreo Totobiegosode, the indigenous people to whom Picanerai belongs.

“Today there are endless threats,” he says, looking straight at the camera. “It’s difficult for us to imagine a future, with the destruction of our territory.”

We’ve driven from Picanerai’s childhood home, a small village in the remote west of Paraguay, to a sentry post established by the Ayoreo on the western frontier of their ancestral land. Beyond that outpost stretches an expanse of protected forest the size of Norfolk, intended to shelter the last indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation anywhere in the Americas outside the Amazon rainforest. Picanerai has never met these nomadic groups, although his father once lived among them. Now, he and his community work to protect them: providing the frontline of defence against the colonisation and destruction of the fragile patchwork of ecosystems that make up their homeland.

“The biggest threat we face is deforestation,” Picanerai explains. “Here they destroy forest mainly to install cattle ranches.”

The Ayoreo’s land is at the epicentre of a global crisis. It is caught in the crosshairs of a force that is ripping down rainforests, extinguishing species, eroding cultures, and fuelling atmospheric changes that could, under the worst predictions, trigger social and economic collapse. That force is industrial agriculture, which is blazing a trail of destruction through the world’s forests, decimating biodiversity and pumping carbon into the atmosphere.

The Paraguayan Chaco – part of a vast lowland plateau named the Gran Chaco, which encompasses parts of Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina and Brazil – is losing forest faster than anywhere else on earth. Between 2001 and 2019, more than 45,000 square kilometres vanished – an area of forest larger than Switzerland, Holland, or Denmark. All this destruction occurred to create space for one industry: cattle ranching.

But the story of the Ayoreo’s fight to protect their territory stretches far further back than 2001. It’s a tale that knits together Jesuit preachers, Mennonite farmers, and fanatical missionaries with the moneyed power of international agribusiness. And today, as the climate crisis gathers pace across the planet, the Ayoreo’s fight has also reached a critical point.

“Our most serious concern today is when we see how the cattle ranchers are destroying our whole territory... If they cut down the whole forest and all of the trees, what will happen to the Ayoreo who are still living there? Where will they find their food, the honey they find inside the tree trunks, and the wild animals that eat the roots of certain plants? If those plants are no longer there, they will die. All of the other animals will die too, and the people will die. They will die of thirst, because everything is being cut down and burned. Every day we watch with great sadness how the white men are destroying the forest, and along with it, how they are destroying our future”

- Mateo Sobode Chiquenoi, former President of the Paraguayan Union of Native Ayoreos [1].

Twentieth century colonialism

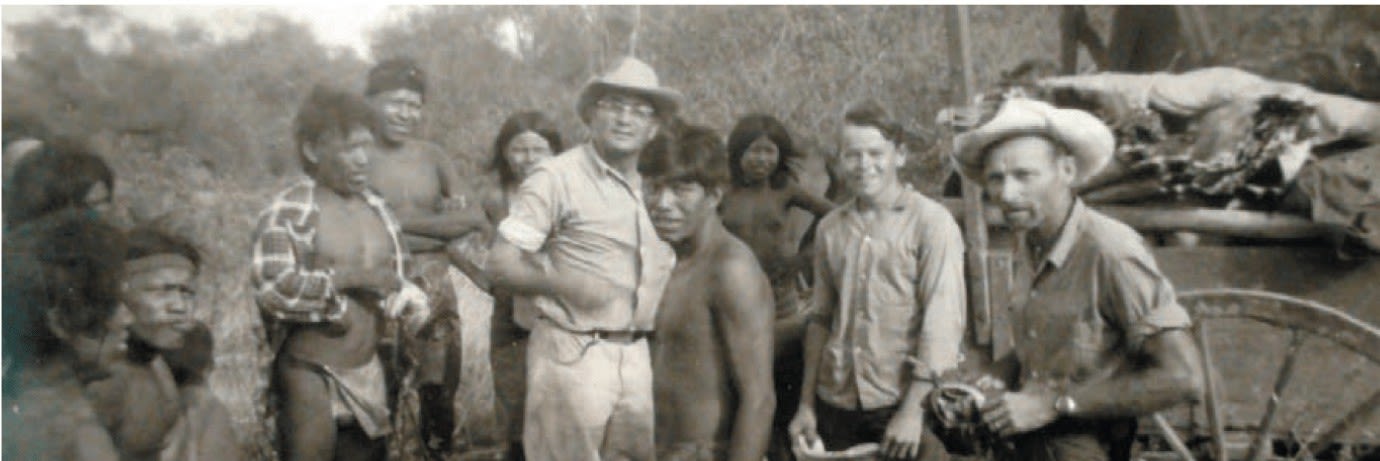

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegosode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching © Survival International/GAT

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegosode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching © Survival International/GAT

For many centuries, the Ayoreo - a loose collection of semi-nomadic, Zamuco-speaking indigenous peoples - have roamed a territory of three million hectares in the heart of South America. Located in the northern Chaco, their home encompasses a patchwork of lowland ecosystems: dense thorn forests, palm-studded savannah, swampy wetlands, cactus scrublands and salt flats.

Thanks to the Chaco’s remoteness, the Ayoreo were spared the worst of the violence and disease that ravaged indigenous America after 1492. Jesuit attempts to convert groups in the early eighteenth century were swiftly abandoned, and the first serious incursions into Ayoreo territory didn’t occur for another 150 years, when frontier farmers arrived in the region. From the 1880s, pioneers installed cattle ranches and tanneries amid the dust and thorns of the Chaco, precipitating fleeting encounters with Ayoreo groups[2].

Decades later, after the upheavals of the first world war, a new wave of immigrants arrived in the Paraguayan Chaco. These were Mennonite farmers, members of a conservative Anabaptist sect whose origins stretch back to sixteenth century Friesland. The first Mennonites arrived from Canada in the late 1920s, lured by promises of state support for those willing to “tame” the Chaco wilderness. They were joined by successive waves of Russian Mennonites, fleeing the famine, hardship and persecution spread by Stalin’s disastrous policy of forced collectivisation[3].

These Mennonite settlers brought with them a force that would transform the lives of the Chaco’s indigenous people: evangelical religion.

Plundering souls

“It was the missionaries who made it impossible for us to continue living in our territory… They prohibited our songs and our vision of the world. They say that all we need is to believe in their God, and that we do not need our territory, but they do not realize that emptying out our territory means emptying out our very way of being”

- Mateo Sobode Chiquenoi [4]

After establishing their first settlements, Mennonite preachers began pursuing indigenous groups living in the surrounding wilds. These early missionary efforts were sporadic: the Mennonites had their hands full eking out a living from their scorching, unforgiving new home, where temperatures frequently sailed above forty degrees. Many Ayoreo groups, often living in the remoter regions of northern Paraguay and southern Bolivia, were easily able to evade them.

This changed in the early 1960s, with the arrival of a notoriously aggressive evangelical organisation from Florida, named the New Tribes Mission. Intent on finding new souls to save, members targeted the most remote indigenous groups. Their contact with the Ayoreo began in 1966. They told them that the end of the world was close, that the forest would soon be destroyed, and that they could survive only by moving to their missionary settlements[5].

Traditionally, the Ayoreo are divided into several sub-groups, each nomadizing a specific stretch of territory in the northern Chaco[6]. Slowly, the competing missionary projects convinced most of them to abandon their lives in the forest - helped, of course, by the disease and ecological disruption brought by settlers since the late nineteenth century.

One sub-group, however, became known for their fierce resistance to the evangelical message. These were the Totobiegosode, whose territory encompassed the southernmost stretch of the Ayoreo’s ancestral land.

In the 1980s, the New Tribe Mission stepped up their efforts to convert the Totobiegosode. They sent members of neighbouring Ayoreo groups - mainly the Garaigosode and the Guidaigosode - to preach to them. They established a mission station, Campo Loro, close to the Totobiegosode territory, in which to house their newest converts.

But the missionaries were entirely ignorant of the political tensions and diplomatic traditions that defined relations between different Ayoreo groups. Unsurprisingly, this led to tragedy. In one instance, in 1986, having spotted a temporary Totobiegosode settlement from a small plane[7], missionaries transported a group of 34 Ayoreo Guidaigosode to preach to the Totobiegosode. Within 15 minutes of encountering their fellow Ayoreo, five of the Guidaigosode were dead[8].

Indifferent to such catastrophes, the missionaries persevered. By the early 1990s, many previously autonomous Ayoreo Totobiegosode were living sedentary lives of poverty and discrimination in stark missionary settlements such as Campo Loro.

From these settlements, the Ayoreo provided a convenient source of cheap labour for the rapidly multiplying Mennonite ranches that dotted the land to the south. Through the intervening decades, these close-knit religious communities had, with immense effort, established productive cattle ranching businesses in the wilderness of the Chaco. Today, the string of dusty Mennonite outposts founded through the 20s, 30s and 40s - Loma Plata, Filadelfia and Neuland - compose one of Paraguay’s richest economic centres. Together, the Mennonite ranching cooperatives account for around a third of Paraguay’s total beef exports, worth more than a billion dollars[9].

“It was as if the missionaries used their evangelization to clear the territory that belonged to the Ayoreo people. That made it easy for the cattle ranchers to buy up almost all of our land, and a few powerful white men took over our territory just like that”

- Mateo Sobode Chiquenoi[10]

Wooden staff with shamanistic feather-signs, left by one of the forest groups in order to bar the entrance to their territory © Amotocodie, 1998

Wooden staff with shamanistic feather-signs, left by one of the forest groups in order to bar the entrance to their territory © Amotocodie, 1998

Ayoreo man Eode at a New Tribes Mission base, Paraguay, 1979. Captured in a manhunt, he died a few days later © Luke Holland / Survival International

Ayoreo man Eode at a New Tribes Mission base, Paraguay, 1979. Captured in a manhunt, he died a few days later © Luke Holland / Survival International

A New York Times article from 1987 on the impact of the New Tribes Mission in Paraguay © New York Times

A New York Times article from 1987 on the impact of the New Tribes Mission in Paraguay © New York Times

Returning home

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco © Earthsight

Cattle ranching is a major driver of deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco © Earthsight

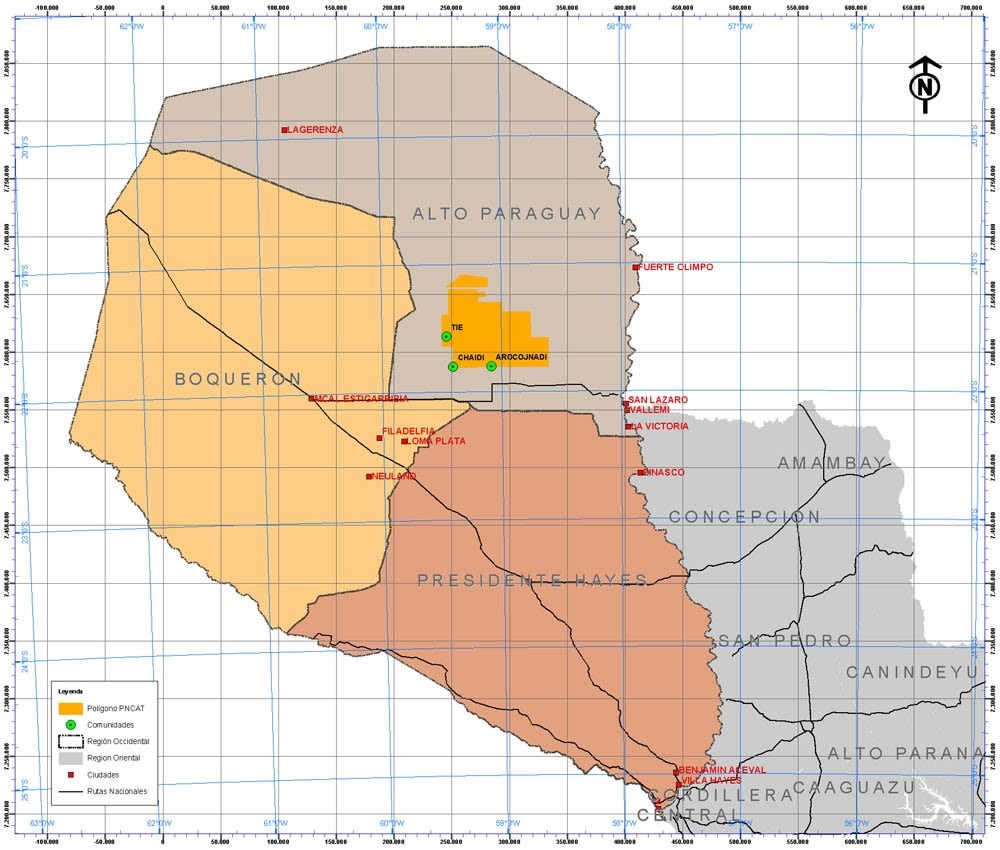

Location of the Patrimonio Natural y Cultural (Tangible e Intangible) Ayoreo Totobiegosode (PNCAT) within the Chaco © GAT

Location of the Patrimonio Natural y Cultural (Tangible e Intangible) Ayoreo Totobiegosode (PNCAT) within the Chaco © GAT

In September 1991, a news item appeared in the back pages of the Paraguayan press. A Mennonite farmer extending his cattle pasture had driven his bulldozer through an “uncontacted” Totobiegosode encampment, forcing the families to flee. For most Paraguayans, the story was a fleeting curiosity. But for the Ayoreo, these few paragraphs of newsprint sparked a revolution. They inspired restless Totobiegosode living at the Campo Loro mission station to strike out and fight for control over their traditional territory - concluding that the only way to protect their siblings still living in the forest was to own the land themselves[11].

Their decision coincided with a massive political realignment in Paraguay. In 1989, after 35 years of surveillance, torture and murder, the Cold War dictator General Alfredo Stroessner was finally driven from power. His regime was replaced by a new progressive constitution which received international praise for its expansion of indigenous rights[12].

In 1993, backed by these new constitutional rights, a delegation of Totobiegosode representatives - most of whom had never seen a city - travelled to Asuncion to lodge their land claim. Noting that their traditional territory was split in two by a road, they decided to fight for 550,000 hectares of land on the eastern side of the highway - an area about the size of Norfolk, which was densely marked by signs of the presence of isolated groups[13].

In 1997, this fight yielded its first concrete victory. Paraguay’s state land institute transferred a property title within the area to the Totobiegosode. In the same year, a group of 12 Totobiegosode families living in Campo Loro decided to leave the mission station and return to their traditional territory, establishing Arocojnadi, the first of two Totobiegosode villages that now lie within the area. The second, Chaidi, was founded in 2004.

“The bigger the extension of our territory, the bigger too is our vision into the future,” explains Tagüide Picanerai, who grew up in Chaidi. “Because without our territory, we can't project forwards as an indigenous culture, we can't look ahead and continue to build from our history, from our land, for ourselves and for our children that are going to live here in the future”.

In 1998, Paraguay’s culture ministry issued a resolution affirming the cultural significance of the Totobiegosode’s traditional land[14]. Three years later, in 2001, it formally recognised the 550,000-hectare territory, officially establishing it as the Natural and Cultural Patrimony of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode: PNCAT by its Spanish acronym (Patrimonio Natural y Cultural Ayoreo Totobiegosode).

The efficacy of such state recognition was limited, however, if ranching firms continued to own the land itself. This fight for property titles continued in the Paraguayan courts: in 2001, two further titles were transferred to the Totobiegosode, extending their freehold to 69,000 hectares. In the context of a country - and continent - with a history of horrendous abuse of its indigenous inhabitants[15], it was a remarkable set of victories.

First contact

But the Totobiegosode, were racing against time. Ranching firms were also chasing titles to the same land. In 2002, despite the protections granted to the area by the 1998 and 2001 resolutions, a Brazilian-owned ranching firm named Yaguarete Porá[16] acquired 78,000 hectares of land within PNCAT. Immediately, the firm brought in bulldozers, clearing roadways and burning vegetation. That year, an investigation by Paraguay’s general attorney’s office found illegal logging for the protected species palo santo on the Yaguarete land, as well as “relentless incursions by bulldozers” - activities which were being carried out without any of the legally required permits[17].

The apocalyptic impact of these clearances for isolated peoples was vividly demonstrated in March 2004, when an isolated Totobiegosode group emerged from the forest.

The group - consisting of seven men, five women, and five children - were first sighted by two settled Totobiegosode leaders. Together with technicians, the settled Totobiegosode were in the process of planning Chaidi, the second Ayoreo village to be established on their ancestral land. While scouting the area for a suitable site to sink a well, they looked up, and saw two of the uncontacted group watching from a distance of 150 metres. The settled Totobiegosode shouted their names, and the two sides - one having left the forest in the eighties, one forced to abandon it now - came together. The older members recognised each other and embraced for the first time in two decades[18].

“They left the forest because their capacity to survive was diminishing every day: the forest, the Eami as the Ayoreo say, was shrinking, and when it's shrinking it's harder to find water or food, to find the fruit and animals which Ayoreo eat,” Picanerai explains.

The forest group decided to join the newly established settlement of Chaidi. A US anthropologist, Lucas Bessire, visited them through the following weeks, listening to their account of their last months in the forest. “They were often forced to camp in the fifteen-metre wide strips of brush left as windbreaks around vast cattle pastures,” he reported. “They went long periods communicating only with whistled sounds; even the children were whisper quiet. If they saw a boot print or heard a chainsaw, they would flee far and fast, leaving everything behind”[19]. At the same time, their water sources were drying up, partly a consequence of deforestation, partly because cattle firms were redirecting streams to irrigate newly built ranches to the south.

A few months after making contact, one of the group’s leaders, Esoi Chiquenoi, issued a call to the Paraguayan authorities. “When we heard the bulldozers, we were very afraid,” he said. “We ran and changed our camping grounds to escape them. We ask the authorities not to touch the forest, to allow the forest to remain, and to stop the bulldozers, because the forest is what gives us life”[20].

An aerial shot of deforestation in the Chaco © Earthsight

An aerial shot of deforestation in the Chaco © Earthsight

Entrance to the Yaguarete Pora ranch in the Chaco © Earthsight

Entrance to the Yaguarete Pora ranch in the Chaco © Earthsight

Deforestation unleashed

A sign denoting the start of PNCAT land, large swathes of which have been illegally cleared for cattle ranching © Earthsight

A sign denoting the start of PNCAT land, large swathes of which have been illegally cleared for cattle ranching © Earthsight

© Earthsight

© Earthsight

The Brazilian ranching firm Yaguarete Porá had denied the existence of uncontacted groups within PNCAT. The dramatic events of 2004 provided incontrovertible proof that they were wrong. But this didn’t stop them clearing forest. Small-scale deforestation continued on their property until, in November 2007, the environment ministry quietly granted them a license to clear 1500 hectares of forest and replace it with cattle pasture.

This egregious act exposed the severe institutional weaknesses undermining the Paraguayan state. At the same time that it approved the Yaguarete license, the environment ministry was participating in a forum on the Totobiegosode land claim, titled “an interinstitutional roundtable for the consolidation of PNCAT”. Led by the UN Development Programme, the forum brought together more than a dozen private and public organisations with representatives of the Totobiegosode. The environment ministry granted Yaguarete the license while these discussions were ongoing – and without consulting any of the other participants.

The license triggered catastrophe for the Totobiegosode’s forests. By the end of 2007, Yaguarete had cleared 1725 hectares. (For scale, one hectare is around the size of a single international rugby pitch). The firm continued clearing forest into 2008, despite calls to cancel the license from various Paraguayan authorities, including the National Environment Council (CONAM) and the Comptroller General’s Office[21]. At the same time, a neighbouring property within PNCAT, titled to River Plate SA and managed by Herbert Spencer Miranda, was also clearing thousands of hectares of forest, destroying 3600 hectares between 2006 and 2008.

Under mounting pressure, the environment ministry revoked the Yaguarete license in November 2008 - by which point Yaguarete had cleared more than 2000 hectares. In 2010, the firm was fined $16,000 for concealing information on the presence of isolated groups in its environmental impact assessment. The court ruled that Yaguarete would have to submit a new assessment before being reissued a license - with the implication that, due to the presence of groups living in voluntary isolation, it was unlikely to be granted. But in late 2013, in flagrant disregard of the court’s ruling, the environment ministry reissued the new license without Yaguarete having submitted any new documentation[22].

This fresh license triggered another wave of catastrophic clearances. The Brazilian ranchers destroyed 5500 hectares of forest through 2014 and 2015. Despite a series of strongly stated resolutions and commitments, the Paraguayan state had comprehensively failed to protect the Totobiegosode territory.

Living in isolation

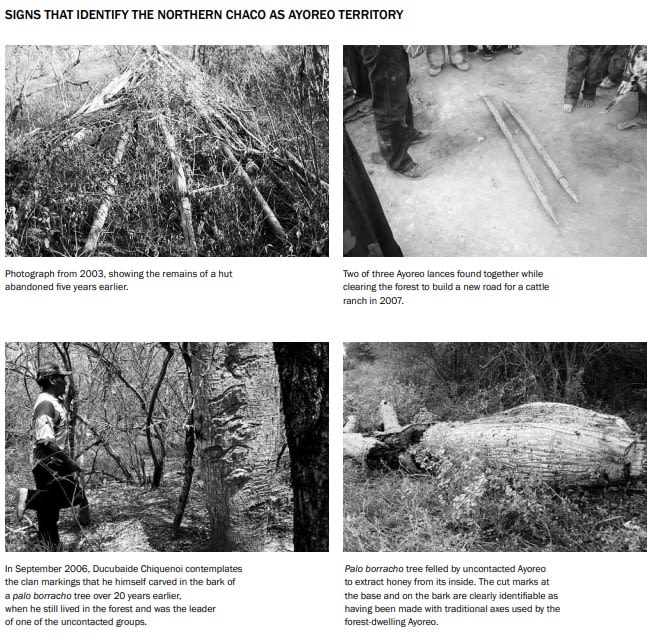

These clearances pose an existential threat to the Totobiegosode groups who evaded the missionaries and the bulldozers and continue to live in voluntary isolation in the forests of the Paraguayan Chaco. “Every few months we see signs of the presence of our brothers in the forest,” Picanerai says. “One of the signs is cuts in the trees: they cut holes in the trees to take out the honey. You can also see the signs of small fires, that's another way to note their presence.”

Since 2004, these signs have been documented by Iniciativa Amotocodie, an NGO advocating for the rights of Ayoreo groups living in voluntary isolation. The Ayoreo’s semi-nomadic lifestyle and traditionally light use of resources - predominantly based on hunting and gathering, with crops grown during the short rainy season - means only fragile remnants are found. But in the wilderness of the Chaco, these signs - abandoned huts, hunting lances, clan markings carved into bark, as well as small firepits and holes cut into trees - are unmistakeable.

“There are many signs that have a comparable age which, considering the distance between the signs, and the simultaneity of their creation, indicates the presence of not one but of various groups,” says Miguel Lovera, director at Iniciativa Amotocodie.

Iniciativa’s analysis shows that the signs consistently appear in areas exposed by the expansion of cattle ranches, Lovera adds.

“The extension of the agricultural frontier - which is supported by the state, by foreign investors, and by financial institutions - means the creation of roads, and the fragmentation of the last forested areas, the last areas of pristine vegetation, that exist in the Chaco. All this means that Ayoreo living in isolation are now facing a situation of extreme vulnerability.”

As indigenous people living in voluntary isolation, the rights of the Totobiegosode (and any other Ayoreo sub-groups that may be inhabiting the remote forests of the Paraguayan Chaco[23]) are afforded extensive protections in international human rights law. A 2013 report from the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights emphasised that the choice to avoid contact is consciously exercised: “Peoples in voluntary isolation cannot be considered ‘uncontacted,’ strictly speaking, since many of them, or their ancestors, have had contact with persons from outside their peoples,” the report notes[24]. “Most of these contacts have been violent and have had serious consequences” for the indigenous peoples, leading them to “reject contact and return to a situation of isolation”.

Furthermore, the United Nations (UN) has established that the act of withdrawing from contact should be interpreted as a withholding of consent for any activities on an indigenous people’s territory. In 2012, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights issued specific guidelines on the rights of isolated peoples in the Amazon and Gran Chaco. They recommended that: “the areas that states have delimited for peoples in voluntary isolation or initial stages of contact must be untouchable…. no rights to exploit natural resources should be granted”[25].

© GAT / Survival International

© GAT / Survival International

Signs of Ayoreo territory © Iniciativa Amotocodie - The Case of the Ayoreo report

Signs of Ayoreo territory © Iniciativa Amotocodie - The Case of the Ayoreo report

Going international

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples from 2014-2020 © UN / Jean-Marc Ferré

Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, the UN Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples from 2014-2020 © UN / Jean-Marc Ferré

Facing the incapacity of the Paraguayan state to uphold its commitment to protect their territory, the Totobiegosode appealed to authorities not subject to the corruption and influence-peddling pervading Paraguay’s institutions, reaching out to the UN and Organisation of American States (OAS).

In November 2014, the UN Special Rapporteur on Indigenous peoples Victoria Tauli-Corpuz visited Paraguay to assess the situation. Her report called on the government to view the situation as an “emergency” and adopt immediate measures to eliminate the risk of unwanted contact with isolated Ayoreo[26].

Her warnings, however, failed to deter the ranching firms. Yaguarete continued to bulldoze forest, clearing 2000 hectares through 2015.

Then, in February 2016, the Inter American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR, part of the OAS) granted PNCAT protected status. This slowed the pace of deforestation within the territory, but far from stopped it all together. Yaguarete cleared 900 hectares in 2017, while further clearance took place on ranches in the centre and north-west of the territory[27].

Help us save Paraguay's most threatened tribe, and their forest home, from destruction: https://t.co/4HeqSyNdVc pic.twitter.com/rkBiB5gUzk

— Survival International (@Survival) April 10, 2016

In response, in a bid to enforce the IACHR’s precautionary measures, Paraguay’s National Forestry Institute (INFONA) issued a series of resolutions in February 2018 that suspended all land management plans granted to properties within PNCAT. This eliminated any ambiguity over the legality of deforestation in the territory: without a valid permit from INFONA, clearing forest is unequivocally illegal.

Grand Theft Chaco

It’s at this point that Earthsight enters the story. As our 18-month investigation Grand Theft Chaco revealed, even this blanket ban wasn’t enough to stop the bulldozers. By analysing satellite imagery and drawing on Paraguay’s land registry, Earthsight identified extensive deforestation on two ranches since INFONA suspended permits.

One is a Mennonite ranch, owned by the cooperative Chortitzer, which cleared 550 hectares between June and September 2019.

The second is Caucasian SA, a Brazilian ranching firm with a property in the east of PNCAT. Caucasian first cleared 2100 hectares between April and October 2018, then paused following legal objections brought by the Totobiegosode, only to restart its bulldozers less than a year later, destroying another 663 hectares of forest between September and November 2019.

We also documented the extent of the destruction wreaked by Yaguarete Porá. The Brazilian firm has destroyed almost 9000 hectares of Totobiegosode forest since the environment ministry first issued the controversial 2007 license, 10 per cent of which occurred after the IACHR granted the area protective measures.

Investigators then traced the onward supply chains linking these ranches to the corporate giants whose demand is ultimately fuelling the clearances. Drawing on trade data, field research and undercover meetings with key supply chain actors, they connected the illegal destruction of Totobiegosode forest to some of Europe’s biggest car firms, including BMW and Jaguar Land Rover.

In September 2020 we published our findings in a 50-page report, which we shared with the Paraguayan authorities. Though the report made headlines in Paraguay and featured in high-profile media elsewhere, the Paraguayan government failed to respond.

The dire consequences of failing to address impunity by agribusinesses in the country would be felt just a few weeks later, as vast forest fires ripped across Paraguay and a national emergency was announced. The fires had been started intentionally by cattle ranchers and soy farmers, often illegally. Paraguayan Ministers, under huge public pressure as haze and smoke choked the country’s capital city, promised tough action against those responsible.

A simple examination of satellite images suggested that the very same ranchers Earthsight had just exposed would be a good place to start. The shocking pictures revealed huge fires at the illegal Chortitzer and Caucasian ranches inside PNCAT, starting in recently bulldozed forest but extending well beyond. One of the fires inside Caucasian was so large the smoke trail extended 80 kilometres downwind.

REVEALED: In early October, Paraguay declared a national emergency as fires raged, with 50,000ha of Chaco destroyed...

— Earthsight (@earthsight) October 21, 2020

Now, Earthsight has discovered around 300 fire hotspots at cattle ranches that feed into BMW & Jaguar Land Rover leather supply chains: https://t.co/4FycP8Bg2t

Earthsight published its fresh evidence but again, nothing was done. Again the government did not respond, although it was quick to defend itself a few weeks later, when Earthsight shared the accounts of whistleblowers denouncing corruption within the environment ministry.

"The illegal clearances and fires by these ranches inside PNCAT are the very dirty tip of a much larger iceberg of impunity in the sector in Paraguay. But they provide a perfect test of the government’s real willingness to bring rule of law to its forests. So far it is a test which it is failing."

Instead of launching an investigation into Earthsight’s evidence of violations of its ban on clearances within PNCAT, INFONA has cosied up to those responsible. It recently signed an agreement with a ranching trade body whose biggest member is Chortitzer, the Mennonite firm which illegally destroyed more than 550 hectares of PNCAT forest. In this agreement, INFONA’s president describes the ranching firms as “faithful examples of sustainable development”.

Facing this inertia, Earthsight – together with a coalition of Paraguayan and international NGOs – wrote to a committee in Paraguay’s Congress which is empowered to investigate environmental crimes.

“Taken together, this represents 3,283 hectares of illegal clearance of some of the most sensitive forest in Paraguay,” the letter reads. “This is around a quarter of the total surface area of Asunción, and almost 10 per cent of the total annual illegal deforestation estimated by INFONA. These substantial criminal acts resulted in the destruction of forest that is essential for the livelihoods of indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation, as recognised by international human rights observers including the UN and the IACHR, as well as for the preservation of Totobiegosode history and culture, with roots that stretch back far beyond the Spanish conquest.”

The letter called on the committee to launch an investigation into this illegal deforestation. At the time of writing, no response had been received. Failure to act could implicate both the Paraguayan state - and the multinational firms whose demand is driving the clearances - in the extermination of a culture that has thrived for centuries among the forests, swamplands and salt flats at the heart of South America. It would also indicate that the many promises Paraguay has been making on the global stage about tackling deforestation and playing its part in the battle to save the climate are just so much hot air.

“I think that when we mistreat our forests, we mistreat ourselves, human beings wherever they are in the world. Because by doing so we create a disequilibrium in nature. And the impacts generated by human beings are returned to us, in one form or another, by mother nature. Today we are facing major climatic changes, in many places people face drought, they face a lack of water, a lack of food, or great fires”

- Tagüide Picanerai

© Earthsight

© Earthsight

Grand Theft Chaco linked the Mennonite-owned Chortitzer cooperative to illegal deforestation of Ayoreo land in the Chaco © Earthsight

Grand Theft Chaco linked the Mennonite-owned Chortitzer cooperative to illegal deforestation of Ayoreo land in the Chaco © Earthsight

Front pages of Paraguay's newspapers on 2 October 2020 show the fire crisis as a national emergency © Earthsight

Front pages of Paraguay's newspapers on 2 October 2020 show the fire crisis as a national emergency © Earthsight

BMW, along with Jaguar Land Rover, was revealed in the report to be buying leather linked to illegal deforestation in Paraguay © Shutterstock

BMW, along with Jaguar Land Rover, was revealed in the report to be buying leather linked to illegal deforestation in Paraguay © Shutterstock