Untamed Timber

The Brazilian flooring giant let off the hook by Bolsonaro’s government and now thriving across the US and EU

- A giant Brazilian tropical wood flooring exporter attempted to censor reports of its connection to a 2018 police operation to investigate suspected illegal practices and which led to the seizure of wood worth millions. Now Earthsight has uncovered the questionable circumstances under which a $123,147 fine was cancelled and its confiscated timber released.

- The head of a national association representing environmental civil servants labelled the decision “shameful” in light of “many signs of irregularities.”

- It is not the only instance of law enforcement efforts being apparently undermined by Ibama officials appointed by the Bolsonaro administration, which has also moved to weaken timber rules while blaming importing countries for Brazil’s illegal timber problem.

- Indusparquet’s buyers – most notably in the US and EU – are importing even larger volumes of the firm’s tropical floor and deck products than before the operation.

- One new customer is a leading US flooring retailer, Lumber Liquidators, the previous recipient of a world record fine for importing illegally sourced wood. The company began buying Indusparquet flooring the month before the bust, despite supposedly strict legality assurance measures imposed on the firm by the US Department of Justice after its prior offence.

Introduction

Hailed as the “largest seizure of illegal Amazon timber in São Paulo’s history,” Operation Patio was a notable feather in the cap for Brazil’s environmental enforcement agency (Ibama) and Federal Police (PF). Yet only a year later, much of the impact from the two-year long investigation would be lost.

In June 2019 Ibama's São Paulo superintendent, Davi de Sousa Silva, a former police officer with no previous environmental experience, cancelled a R$482,300 fine ($123,147 at the time) levied by Ibama agents against Indusparquet, Brazil’s largest wood floor and deck exporter.

As part of the decision, superintendent Silva, appointed by Jair Bolsonaro’s government only months earlier, released over 1600 m³ of wood that had been seized at an Indusparquet subsidiary during Operation Patio. The timber was valued at $2.5 million by Ibama at the time.

Six months before the cancellation of this fine – during a previous federal administration – Ibama had confirmed a separate R$450,000 ($117,059 at the time) fine against the company for having over 10,700 m³ in timber credits in the federal agency’s electronic control system without the corresponding wood in the yard, which is illegal under Brazilian law.

Both the confirmed and cancelled fines were part of Operation Patio, an investigation instigated after a suspicion by Ibama that one of its staff might be implicated in fraudulent schemes to launder illegal tropical timber. Such schemes allegedly allowed companies to hide illegally-extracted timber among other timber obtained legally.

The investigation culminated in the timber seizure at Indusparquet in late May and early June 2018. The company was also temporarily banned from trading timber and slapped with a total $186,692 in fines, as previously reported by Earthsight.

Indusparquet has denied any wrongdoing and claimed that all its timber is of legal origin.

This was not the only time that environmental officials appointed under President Jair Bolsonaro’s administration appear to have sided with corporations in an illegal timber case. Officials named by Bolsonaro have actively attempted to weaken timber rules, making it harder to detect illegal timber and punish perpetrators. In the meantime, Bolsonaro himself has threatened to point the finger at countries apparently buying illegal Brazilian timber.

Despite the Operation Patio revelations, Indusparquet exports increased in the years after. The US, by far its main foreign market, now receives around 15 per cent more Indusparquet wood products than it did before.

Indusparquet’s exports – which have topped 55,000 tonnes in the last five years – include some of the species most targeted by illegal loggers in Brazil: Ipê (Tabebuia serratifolia), Cumaru (Dipteryx odorata), Angelim (Hymenolobium petraeum), and Tauari (Couratari guianensis). These are also among the species seized by Ibama in 2018.

"The largest seizure of illegal Amazon timber in São Paulo's history"

US buyers of Indusparquet products are engaging in a risky bet. Under the country’s Lacey Act, firms are banned from importing timber illegally sourced in another country. Timber companies which are under investigation for a lack of compliance with timber legislation should present a red flag to any buyers.

In 2016 US retail giant Lumber Liquidators (now LL Flooring) was fined $13 million for importing illegal Russian timber – a world record penalty for such an offence. Despite being placed in probation and forced to implement a strict due diligence system, Earthsight analysis shows how the company has become one of Indusparquet’s largest customers.

While largely unaffected by the investigation and its findings, Indusparquet has sought to erase it from history by requesting that renowned environmental media outlet Mongabay remove a previous article from its website, based on misleading claims that the company has been found entirely innocent.

Some of the Indusparquet wood inspected during Operation Patio. Credit: Ibama

Some of the Indusparquet wood inspected during Operation Patio. Credit: Ibama

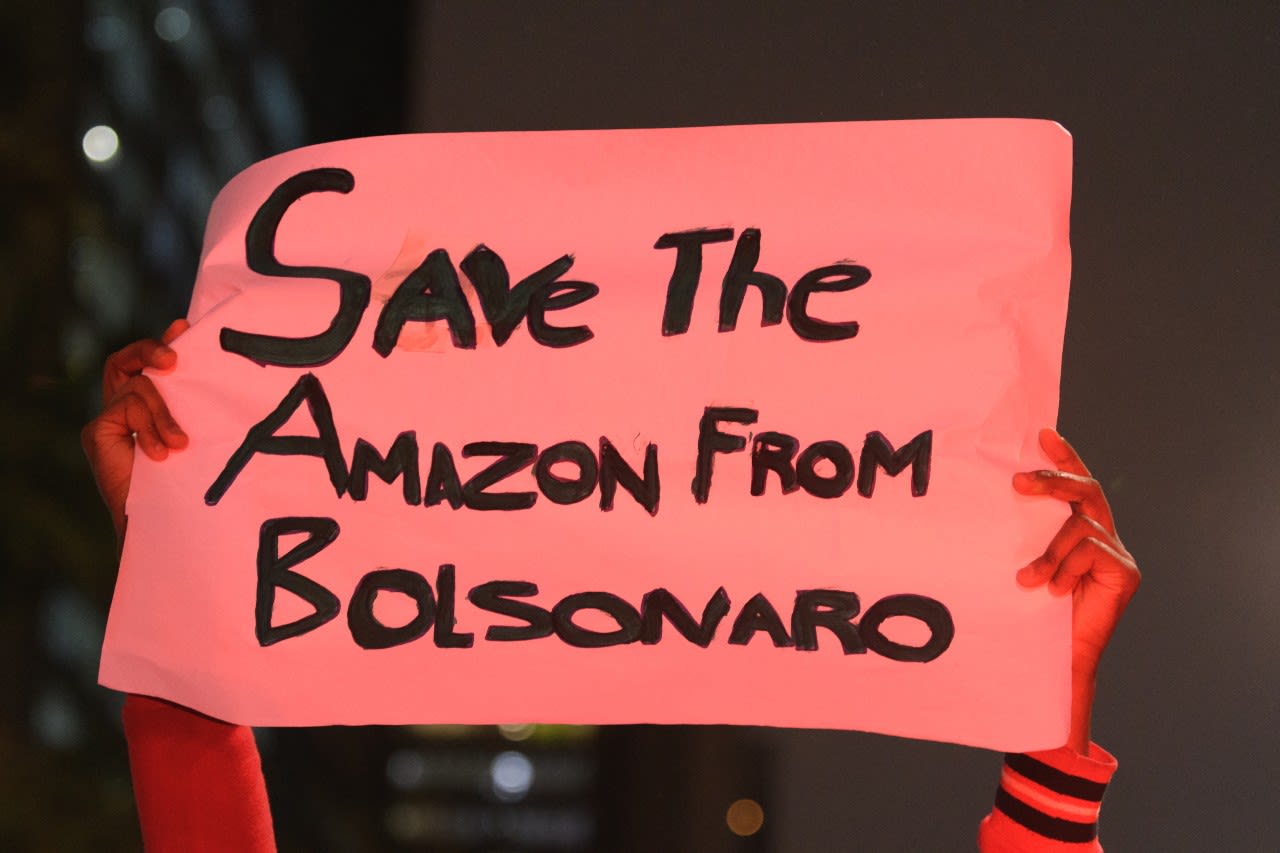

The Bolsonaro government has actively attempted to weaken timber rules, making it harder to detect illegal timber and punish perpetrators. Credit: Shutterstock

The Bolsonaro government has actively attempted to weaken timber rules, making it harder to detect illegal timber and punish perpetrators. Credit: Shutterstock

Demand for Brazilian timber coupled with weakening protections is putting increasing pressure on the Amazon and other biomes. Credit: Shutterstock

Demand for Brazilian timber coupled with weakening protections is putting increasing pressure on the Amazon and other biomes. Credit: Shutterstock

A 'shameful' decision: Ibama's change

of heart

Ibama officials inspect an Indusparquet facility during the Operation Patio investigations. Credit: Ibama

Ibama officials inspect an Indusparquet facility during the Operation Patio investigations. Credit: Ibama

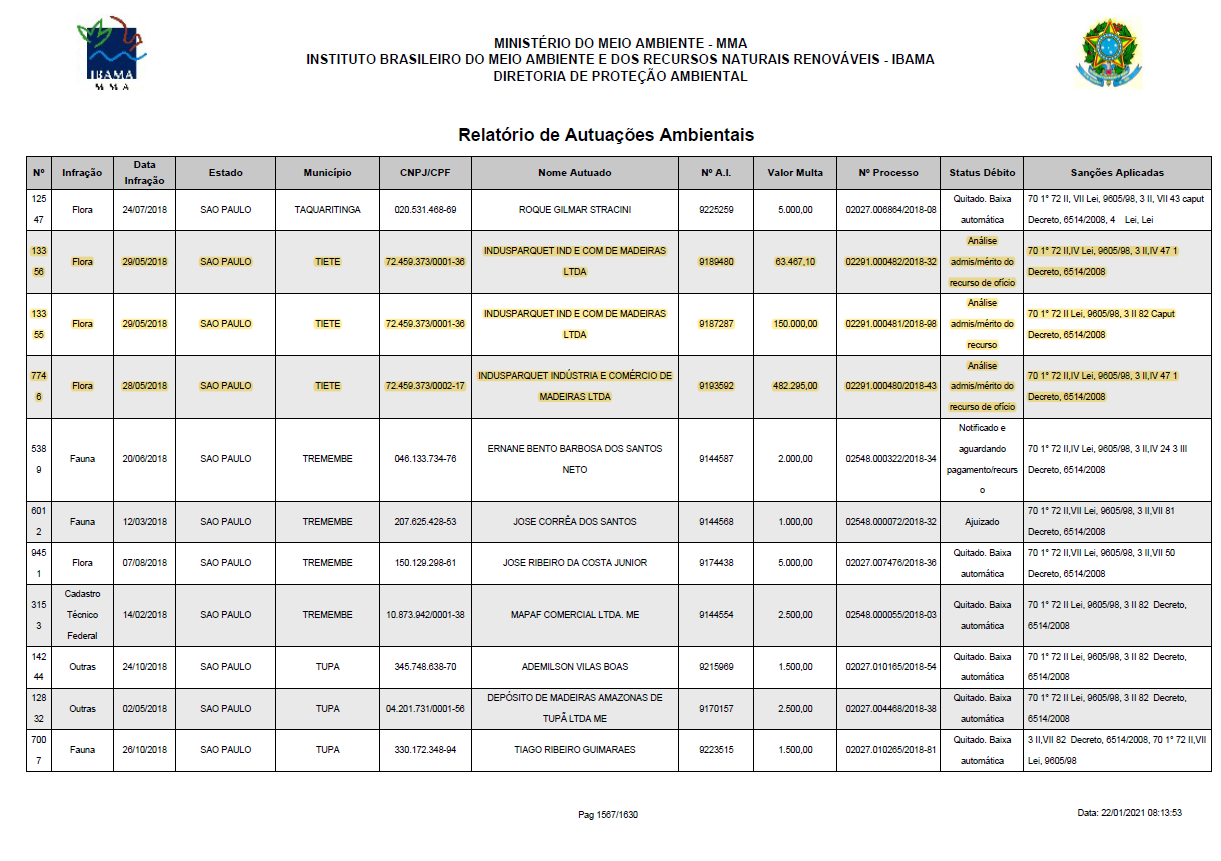

Government database shows three fines issued to Indusparquet across two days in 2018, the second of which was later tripled to R$450,000, while the largest one was cancelled. Source: Ibama

Government database shows three fines issued to Indusparquet across two days in 2018, the second of which was later tripled to R$450,000, while the largest one was cancelled. Source: Ibama

One of two Indusparquet facilities located in Tiete, São Paulo. Source: Google Earth

One of two Indusparquet facilities located in Tiete, São Paulo. Source: Google Earth

In the December 2018 decision confirming one of Indusparquet's fines, Ibama’s then São Paulo superintendent, José Edilson Marques Dias, said that “the authorship and materiality [of the infraction] have been duly established.” The infraction notice alluded to the “inconsistency between the amount of physical timber in the yard and the amount registered in [Ibama’s] system.”

Dias concluded that the initial fine (R$150,000) against Indusparquet's headquarters should be tripled to R$450,000 due to reoffending. As public records show, the company had already been fined by Ibama in 2017 for misrepresentation.

Part of the justification for his decision was that the investigation and the conduct of his agents had been in accordance with standard procedures and within the law. Six months later, his successor would adopt the opposite view.

To justify cancelling the R$482,300 fine against an Indusparquet subsidiary, Colonel Silva pointed to “defects” in the investigation and in Ibama agents’ actions. No evidence of such “defects” was provided in Silva’s ruling and Ibama did not respond to Earthsight’s questions around the cancelation of the fines.

Colonel Silva is not a career environmental agent, nor does he have any expertise in environmental issues

The superintendent appointed by the Bolsonaro government accepted Indusparquet's arguments and considered “the production of new evidence or information unnecessary” concluding that Indusparquet had been right and his agents wrong. Silva ordered the immediate release of the timber (which would fill more than 70 trucks) and the cancellation of the fine.

“The applicant claims that all the timber, which is the subject of the fine, has a legal origin, and that the timber inspected at the site is from Indusparquet’s headquarters and is covered by a license,” wrote the colonel. He also claimed not to see any evidence of reoffending, despite the 2017 fine against Indusparquet’s headquarters and the 2018 fine confirmed by his predecessor only six months earlier.

Colonel Silva is not a career environmental agent, nor does he have any expertise in environmental issues. He took over as Ibama’s São Paulo superintendent less than two months before signing the cancellation of one of Indusparquet’s fines.

In April 2019 the Environment Minister who appointed him, Ricardo Salles, had a whole floor of Ibama's offices in São Paulo, 1,000km from the capital Brasília, refurbished and began working from there frequently. This was an unusual move for a federal government minister, as highlighted by the Brazilian press at the time. Before joining Bolsonaro’s government, Salles was convicted in 2018 for defrauding environmental maps to favour mining companies during his stint as São Paulo State Secretary of Environment.

Elisabeth Uema, executive secretary of the National Association of career civil servants specialised in environmental issues (Ascema), told Earthsight: “The cancellation of the fine by Superintendent Silva gives us an example of what could happen at the national level.

“As of January 2020, initial rulings on fines have been the sole responsibility of Ibama's superintendents, who in the vast majority are not career civil servants specialised in environmental issues. They were appointed by Minister Ricardo Salles to serve the Bolsonaro government's political interests. It is shameful that this fine has been cancelled in light of the many signs of irregularities.”

In a statement sent to Earthsight, Indusparquet points to Ibama’s recognition of the legality of its timber and claims that during Operation Patio “nothing wrong was identified at Indusparquet.” The company alleges Ibama only detected “possible administrative inconsistencies" mostly related to the conversion of sawn timber to finished products in Sinaflor. The company states such inconsistencies have since been rectified and do not justify the timber seizure or the large fines levied (read Indusparquet’s full statement, in Portuguese, here).

The decision to cancel one of the Indusparquet’s fines and release its confiscated timber is not yet final. A search for the case number on Ibama’s website indicates that the case is still under analysis by higher ruling authorities within Ibama’s Brasília headquarters.

Questioned about any criminal proceedings resulting from Operation Patio, the Federal Police told Earthsight that “several indictments were carried out during the investigation based on the material obtained.” The Federal Police did not specify the identities of those indicted citing secrecy rules. Earthsight has no evidence on whether any of those indicted have any links to Indusparquet.

Minor negligence or serious violations?

Ibama monitors timber exploitation and trade in Brazil through an electronic system called Sinaflor, which is akin to how money moves between bank accounts. Whenever the agency authorises timber extraction in a given area, Sinaflor allocates virtual timber credits to the concession holder detailing species and volumes to be cut. All timber sold by the concession holder must then be transferred to buyers via Sinaflor (i.e. the seller’s timber credits in Sinaflor are relocated to the buyers). For each transaction a document known as a DOF is generated to accompany the shipment – attesting to its origin and legality. Moving or holding timber without the corresponding DOF or Sinaflor credits is illegal.

The rule is clear: “[T]he transfer of forest products between yards of the same company must be accompanied by the corresponding document of origin (DOF), and this document must be issued based on yard stocks duly accounted for in the system.”

It is common among timber companies in Brazil to launder illegal timber by not cancelling their timber credits on Ibama’s system, as a 2018 Greenpeace report pointed out. This practice allows them to generate fictitious credits to cover wood of illegal origin.

While Indusparquet claims that the 1600 m3 of timber seized at its subsidiary was of legal origin, the company committed major infractions by allowing its physical stocks to differ significantly from the volumes declared in Sinaflor.

Former Ibama president Suely Araújo, who headed the agency during the 2018 operation and left at the start of the Bolsonaro government, told Earthsight: “I think it is essential that environmental enforcement agents be strict about how companies register their timber in [Sinaflor], which is the most important tool we have to check the origin of the timber.”

Since the investigation culminated in the search and seizure operation against Indusparquet’s warehouses in mid-2018, the company has argued that all the timber stored at its subsidiary belonged to its headquarters, and that this was the reason why the timber lacked the corresponding permits. However, Indusparquet was fined precisely for declaring 10,700 m³ of timber (of different species) on Ibama’s electronic system without actually having the corresponding timber at its headquarters’ warehouse.

In order to demonstrate that it had not committed an infraction at its subsidiary, the company presented another illegality at its headquarters – for which it was fined – as an argument in its defence. It is unclear why Ibama’s São Paulo superintendent then accepted Indusparquet’s argument.

It is shameful that this fine has been cancelled in light of the many signs of irregularities

“The law enforcement operation carried out in 2018 at Indusparquet found inconsistencies in the origin of the timber registered in [Ibama’s electronic] control system and in the volumes found at the company's yards. There was a huge amount of timber credits registered for Indusparquet's headquarters with no corresponding timber stock at the yard, which is illegal.

“Another illegality was also found at [Indusparquet’s] subsidiary, but with the opposite situation: timber at the yard without any corresponding balance or proof of origin in the system,” Araújo added.

In their 2018 report, Ibama agents highlighted the claim made at the time by Indusparquet managers that they were not aware about the need to issue DOFs to move timber from the company’s headquarters to its subsidiary. As a market leader operating for 50 years in domestic and global markets, Indusparquet’s claims of ignorance of long-standing timber rules ring hollow.

In its response to Earthsight, Indusparquet says Ibama made several mistakes while counting the company’s stocks and that the discrepancies detected by the agents do not actually exist once conversions between sawn timber and finished products are correctly taken into account. The firm also argues Ibama should have let it rectify the system before deciding on sanctions.

However, Ibama’s legal rule states that once timber has been converted to finished goods, the new volumes must be registered no later than the following day. In addition, the rule stipulates that Ibama must only provide deadlines for rectifications for products that were processed the day before inspection, and not for the whole stock.

Dias, the superintendent who confirmed one of the fines against Indusparquet, reported in late 2018 that, during Ibama inspections at the two Indusparquet yards over six days, “the company was asked to carry out the necessary updates / conversions in the system […]. However, according to [Indusparquet], only two of its employees were in charge of updating the system, one of whom was out on a trip and the other had been arrested by the Federal Police at the beginning of the operation, so there was no way to update the system.”

The firm argues that the fine over the discrepancy of 10,700 m3 at its headquarters should be reduced because the consequences to the environment were allegedly accepted by Ibama as being “negligible.” Yet, according to maximum conversion rates applicable under Brazilian law for timber management plans, this amount of wood is equivalent to over 3500 hectares of forest (or around 4900 football pitches).

According to Indusparquet, the company meets all its legal responsibilities in regards to Ibama’s DOF system and only sources timber of legal origin.

Nonetheless, the firm admits mistakes were made and claims it has since “perfected its controls and adjusted the department responsible for this activity” in order to carry out updates of Sinaflor more frequently and in ways that reflect its physical stocks more accurately.

Source: Ibama

Source: Ibama

The system aims to reduce exploitation and laundering in Brazil's timber sector. Credit: Shutterstock

The system aims to reduce exploitation and laundering in Brazil's timber sector. Credit: Shutterstock

Ibama agents inspect sawn timber in the Amazon state of Rondonia, 2018. Credit: Creative Commons

Ibama agents inspect sawn timber in the Amazon state of Rondonia, 2018. Credit: Creative Commons

Damage limitation

Lawyers for Indusparquet have attempted to erase media coverage of the 2018 Operation Patio revelations. Source: Mongabay

Lawyers for Indusparquet have attempted to erase media coverage of the 2018 Operation Patio revelations. Source: Mongabay

Late last year, Indusparquet’s lawyers contacted Mongabay – the environmental news outlet that had published a version of Earthsight’s 2018 investigation – requesting the organisation to take down the article from its website or de-index it.

The attorneys justified their request by claiming that “several facts were reported without necessary context and/or that some details conveyed in this article are wholly incorrect,” without however detailing the alleged errors. They also highlighted the fact that Indusparquet “has suffered enough as a result of this situation and the subsequent reporting on it.”

Rhett Butler, Mongabay’s founder and CEO, told Earthsight the request “was accompanied by the false claim that Mongabay had not contacted Indusparquet in advance of the article's publication. The article in fact quotes Indusparquet spokeswoman Flavia Baggio objecting to the investigation's findings.”

Butler also said “it's very unusual for Mongabay to receive a demand to take down an article without more substantiation of claimed inaccuracies,” and that “at present we do not see any errors or inaccuracies in our reporting that would warrant modifications to the story.”

Disempowered agents, weakened rules

This is not the only instance Ibama’s decisions being reversed by new superintendents or directors appointed by the Bolsonaro government.

Recently, Ibama’s superintendent in Bahia state reversed a decision by field agents to suspend work at a resort that affected the largest sea turtle conservation project in Brazil. The superintendent allegedly disregarded the advice of his technical staff in violation of current rules. The case is being investigated by the Federal Prosecutor's Office and a court has already ordered the works to be stopped again.

In March last year The Intercept Brasil reported that Ibama’s superintendent in the state of Pará, another recent Salles appointee, had retroactively signed off on exports lacking the appropriate Ibama licenses. With the measure, the superintendent allegedly cleared five containers belonging to British firm Tradelink that had been detained at importing countries due to lack of appropriate permits. The Intercept also noted that Tradelink owed Ibama over $1.1 million in fines at the time.

Timber law enforcement has been increasingly rolled back under the Bolsonaro regime

Soon after, Ibama’s president Eduardo Bim – another Bolsonaro appointee – is claimed to have refuted the expert views of five internal analysts and scrapped such export permits altogether. The licenses had been used to ensure that shipment volumes and species were correctly declared by exporters.

According to Ascema's executive secretary Elisabeth Uema, of Ibama’s 26 state offices, 21 are currently led by superintendents without an environmental background and whose appointments were based on “strictly political criteria.”

Under Bolsonaro, Ibama and the Ministry of Environment have contradicted expert opinion and barred measures that would strengthen law enforcement over the exports of Ipê, one of Brazil’s most valuable species and which was among those seized by Ibama at Indusparquet’s yard.

Despite these deliberate efforts to undermine domestic timber law enforcement, Bolsonaro recently threatened to name and shame countries allegedly importing illegal Brazilian timber, including those most critical of his environmental policies. He has since backed down from doing so, instead suggesting he will accuse specific importing companies.

Of Ibama’s 26 state offices, 80 per cent are led by superintendents without an environmental background

Earthsight first contacted Ibama for comments on the statements contained in this article on 18 January 2021 but, despite repeated requests for comment, received no reply by the time of publication.

Conservation efforts in Praia do Forte were threatened after Ibama's Bahia chief Rodrigo Santos Alves ignored advice to block a major construction project. Credit: Shutterstock

Conservation efforts in Praia do Forte were threatened after Ibama's Bahia chief Rodrigo Santos Alves ignored advice to block a major construction project. Credit: Shutterstock

Ibama president Eduardo Bim is accused of disregarding expert opinion in a move which led to weakened timber regulations. Credit: Creative Commons

Ibama president Eduardo Bim is accused of disregarding expert opinion in a move which led to weakened timber regulations. Credit: Creative Commons

The Bolosnaro regime's anti-environment agenda has long drawn ire from many in Brazil. Credit: Shutterstock

The Bolosnaro regime's anti-environment agenda has long drawn ire from many in Brazil. Credit: Shutterstock

Failing laws allow risky US, EU imports

Indusparquet's dedicated US website promotes its supply of Brazilian Chestnut, Brazilian Oak and other species used for its flooring. Source: Indusparquet

Indusparquet's dedicated US website promotes its supply of Brazilian Chestnut, Brazilian Oak and other species used for its flooring. Source: Indusparquet

Flooring made from Jatobá (Brazilian Cherry) is a popular Indusparquet export. Credit: Creative Commons

Flooring made from Jatobá (Brazilian Cherry) is a popular Indusparquet export. Credit: Creative Commons

US retail chain Lumber Liquidators has become a key Indusparquet client in the years after Operation Patio. Credit: Shutterstock

US retail chain Lumber Liquidators has become a key Indusparquet client in the years after Operation Patio. Credit: Shutterstock

The EUTR law designed to prevent suspect timber and wood product imports has been found wanting. Credit: Earthsight

The EUTR law designed to prevent suspect timber and wood product imports has been found wanting. Credit: Earthsight

Indusparquet claims to be “the world's leading producer of premium hardwood flooring.” It boasts of having supplied wood flooring to the Vatican, the Taj Mahal, the Mirage Hotel in Las Vegas, and Dolce & Gabbana shops in Milan.

It is among Brazil’s 20 largest multinational corporations, with three manufacturing plants in the country and distribution centres in the US, Italy, France and Argentina. In Brazil, the company controls Compensados Império Ltda, a manufacturer of engineered floors – multi-layered products with a top surface of tropical wood. It sells these products under the brand Masterpiso.

In the last five years Indusparquet exported over 55,000 tonnes of solid wood floors and decks to nearly two dozen countries. International trade data analysed by Earthsight shows that, despite Indusparquet’s claims of significant negative impacts to its business, Operation Patio has had no effect on its exports. The company’s exports in the two and a half years following the operation’s initial revelations have in fact increased compared to the previous two and a half years.

90 per cent of Indusparquet exports are destined for the US

The US is by far the main destination for Indusparquet's products – made from species that include Cumaru (Brazilian teak), Tauari, Jatobá (Brazilian cherry), Sucupira (Brazilian chestnut), Ipê, and Angelim – accounting for over 90 per cent (49,600 tonnes) of the firm’s worldwide sales. US importers’ unrelenting demand for Indusparquet’s products – with a 15 per cent rise in volumes following Operation Patio – largely explains the growth in the Brazilian firm’s exports despite its well-publicised breach of Brazilian laws on timber certification.

In addition to Indusparquet’s own export volumes, its subsidiary, Compensados Império, is itself a large exporter of engineered wood floors. In the past five years the company has exported over 19,000 tonnes of engineered Masterpiso floors to the US, both directly to large retailers and for distribution by Indusparquet’s subsidiary in Florida, Brw Floors. Masterpiso floors are made from Jatobá, Ipê, Sucupira and Brazilian Koa (Tigerwood), among others.

Indusparquet export volumes before and after Operation Patio

There is reason for US firms to be vigilant when sourcing from timber companies which are under investigation for a lack of compliance in their certification processes or supply chains. Under the country’s Lacey Act, firms are banned from importing timber that was illegally sourced in another country. The severity of sanctions against guilty companies depends on the efforts made by them to avoid such scenarios. This means they should be diligent in verifying the legal origin of their imported wood products.

One case in particular provides a cautionary tale.

In 2016 US retail giant Lumber Liquidators, the now re-branded LL Flooring, was sentenced by the Department of Justice for importing illegal timber from the Russian far east and levied with the largest illegal timber import-related fine in history – $13 million. The company was forced by US authorities to implement a strict system meant to prevent any risk of further purchases of illegal wood and put under a five-year probation period. Nevertheless, Lumber Liquidators has since become one of Indusparquet’s largest customers.

In late April 2018 – a month before the raids at Indusparquet took place – Lumber Liquidators started purchasing Masterpiso engineered floors. It appears that instead of reviewing its purchases from Indusparquet in light of reports of the raids, the firm actually increased them through 2018 and 2019.

Imports in 2019 were more than double those of the previous year. Purchases have continued to-date, with the most recently recorded arriving in late December 2020. Between May 2018 and the end of Lumber Liquidator’s probation period on 6 October 2020, the company imported at least 6.3 million square metres of this flooring, with an approximate retail value of $6 million.

While Earthsight has no evidence to indicate that the specific wood floor products imported by Lumber Liquidators – or any other importer – from Indusparquet were illegally sourced, evidence against the Brazilian firm suggests that the wood was at risk of being illegally sourced.

Furthermore, under the Lacey Act government paperwork or third-party certifications accompanying the wood does not necessarily eliminate the risk that it will be subsequently shown to have been illegally sourced. It is questionable whether purchasers could have been confident of the origin of Indusparquet’s timber in the immediate wake of the Ibama bust and arguably this remains the case. Yet nothing in Lumber Liquidators’ Lacey Act compliance plan appears to have prevented the company from purchasing from Indusparquet.

Earthsight made repeated attempts to seek comments from Lumber Liquidators but received no reply by the time of publication.

Indusparquet told Earthsight that in December 2018 an American client audited the company’s operations and procedures in detail, leading to “extremely satisfactory” results. The firm says the auditors found no evidence of illegal timber and agreed that Operation Patio had been flawed. When questioned about the client’s identity and asked for more details of the audit process, Indusparquet declined to respond citing contractual restrictions.

France, Italy and Belgium have continued to import Indusparquet wood products into Europe following Operation Patio, while Denmark has since become a new destination. Together, these countries have bought over 1,000 tonnes of Indusparquet goods in the last five years.

Imports into Italy and Belgium have significantly increased since May 2018. Similar to their US counterparts, European firms operate under laws that ban the import of illegal timber. The European Union Timber Regulation (EUTR) also forces importers to carry out due diligence to ensure that the risk of buying illegal wood is reduced to a negligible level.

In 2018, Earthsight revealed that Floor & Decor, the US’s largest flooring retailer, had been buying wood floors from Indusparquet before the seizure and had continued thereafter, potentially risking severe penalties under the Lacey Act. Analysis of trade data suggests that Floor & Decor has now dropped Indusparquet as a supplier. But by picking up new customers, most notably Lumber Liquidators, Indusparquet’s US trade has not only remained unaffected by the scandal but has thrived.