The Fixers

How a failing US law allowed a Brazilian flooring giant to flood America with millions of dollars of suspect wood

Key Findings

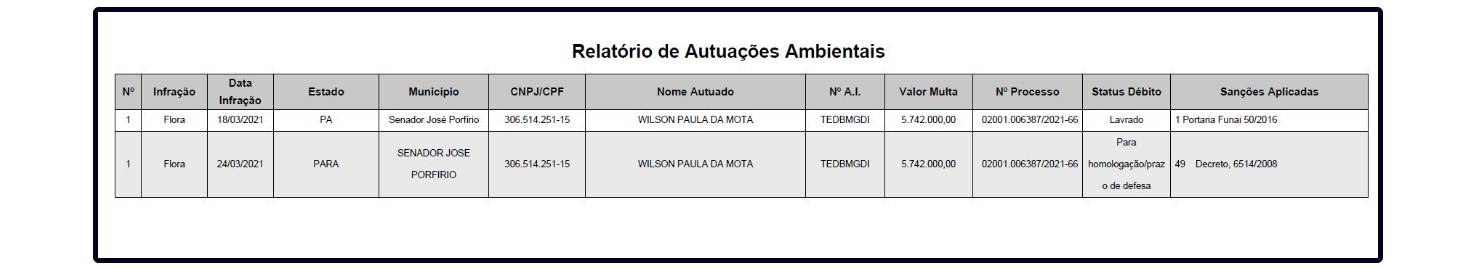

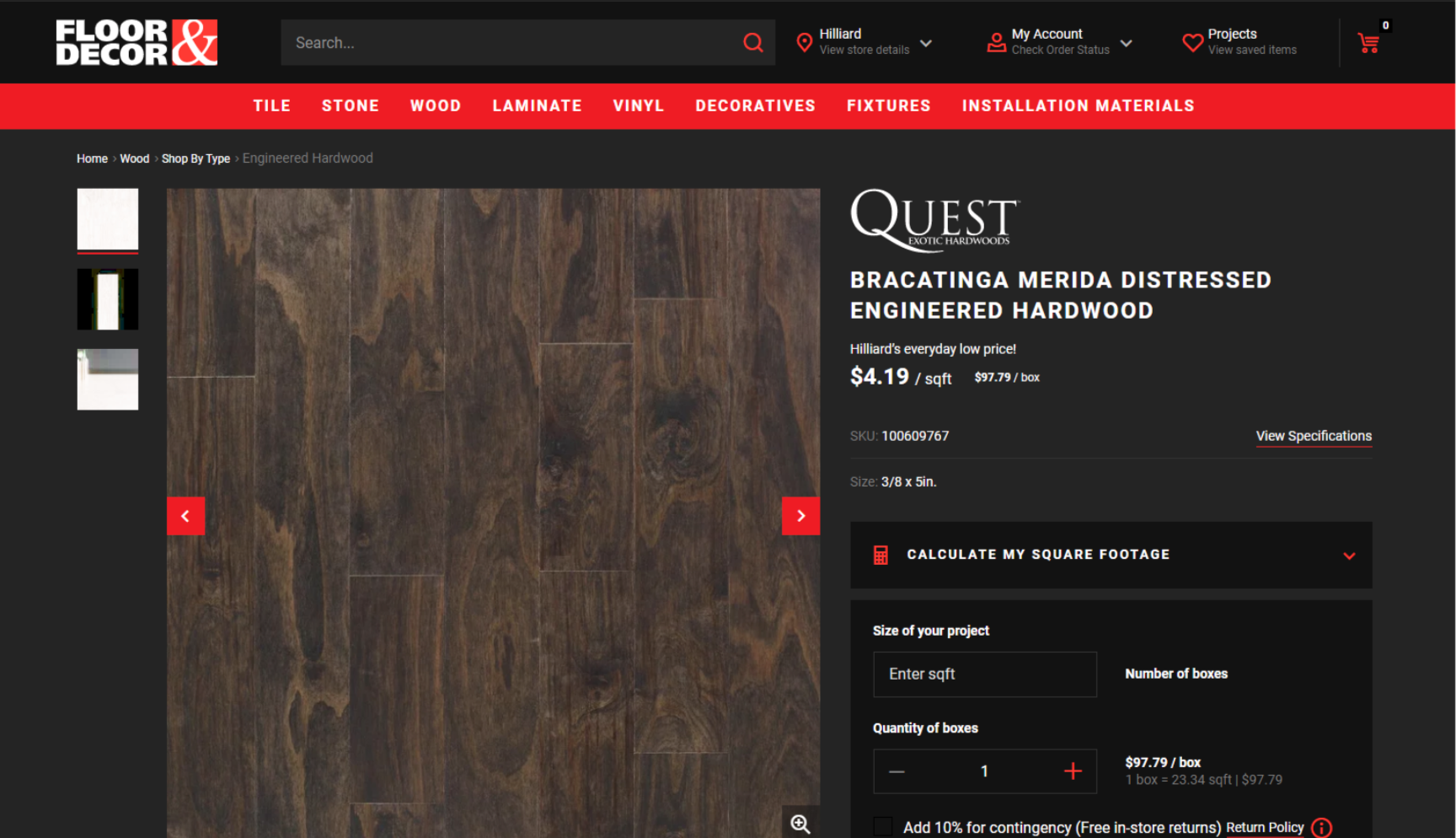

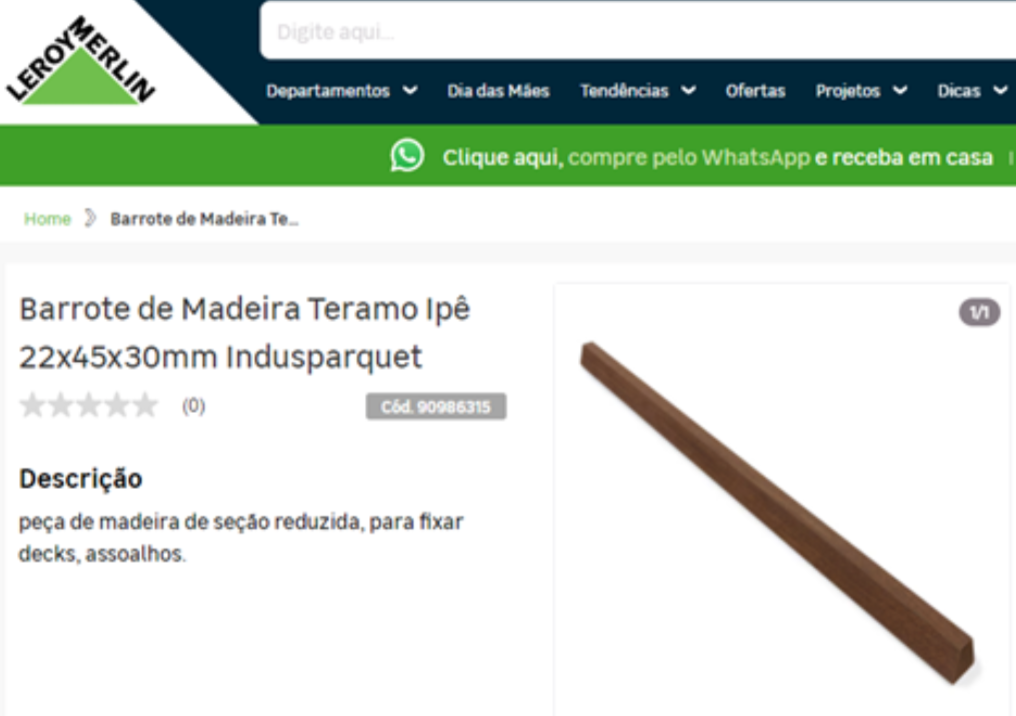

- From the unique Atlantic Forest to the Amazon, Earthsight and Mongabay's year-long investigation reveals how exotic wood flooring linked to illegal logging, from a firm embroiled in multiple corruption cases in Brazilian courts, has been pouring into the US over the last five years.

- We detail how Indusparquet is charged with using fixers to illegally grease the wheels of its timber supply chains, how it has sourced wood from indigenous lands and from suppliers fined millions for illegal practices to make its products.

- The Brazilian firm's flooring has been sold by retailers all over the US, including major home store chains. One US firm was able to buy suspect wood despite having its purchases closely monitored by US authorities.

- The findings show a US law meant to prevent imports of stolen wood is failing and highlight the urgent need for further action to halt imports of 'forest risk commodities' from countries like Brazil

- Read the full list of key findings.

- Read Earthsight's recommendations.

The Fixer in Paraná

"We have already agreed. He will saw the wood, we just need you to sort things out."

"We had done some business with bracatinga [...] By request of a client in the United States who liked the wood, we went after buying more bracatinga."

A match made by God

These were hectic days for the residents of União da Vitória, a small town nestled in the Atlantic Forest, in Paraná in Brazil's south. It was September 2016 and municipal elections were scheduled to take place the following month. Like everywhere else in this South American country during this period, meetings between candidates and their supporters were part of the daily routine for many of its inhabitants.

As a politically active citizen, in his downtime from his day job as the regional head of the Paraná Environmental Institute, an agency tasked with licensing forest enterprises and handing out logging permits, André Aleixo was busy attending rallies promoted by his favoured candidate. What he probably didn't expect was that at one of these events, after a long day of work, he would meet Luiz Roberto Granatyr, the owner of a local sawmill. For him, it was one of those amazing coincidences or, in his words, proof of "how God does the right thing"1 by bringing to his door someone he was desperate to meet.

In a call involving the two that must have taken place soon after they shook hands and introduced themselves, Aleixo's excitement at meeting Granatyr is obvious. We know this because unbeknownst to the two men, the phone call was being tapped.

While a group of investigators from the public prosecutor's office in the nearby town of Guarapuava were looking for evidence of wrongdoing by public officials involving environmental licensing in Paraná2, they stumbled on something even darker: a suspected corruption scheme involving Aleixo and José Antonio Baggio, one of the owners of Brazil's largest flooring company, Indusparquet.

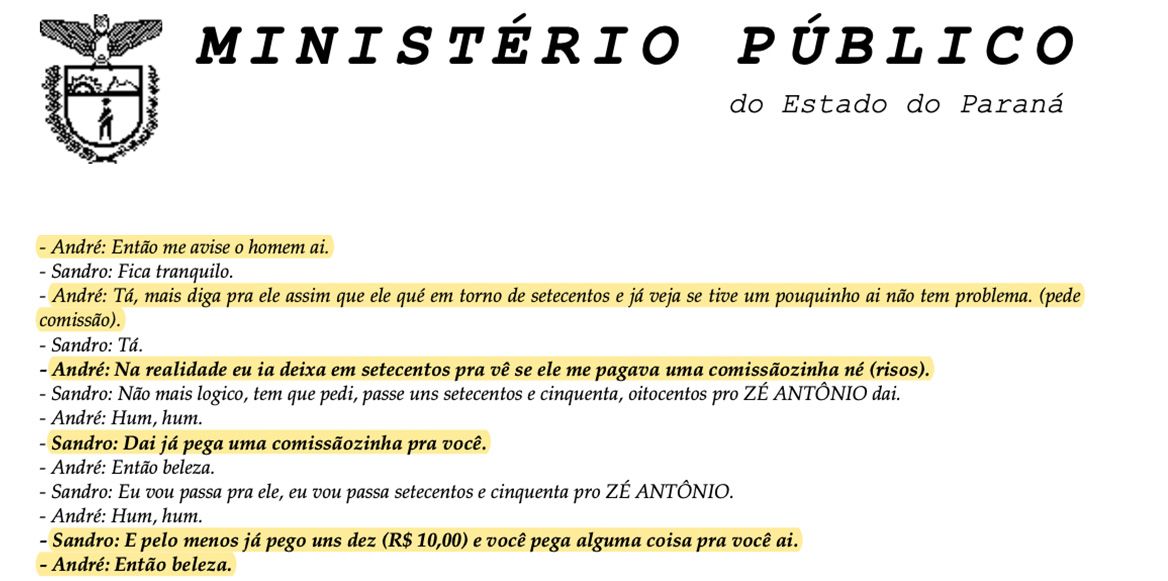

This first wiretap recorded a conversation that commenced at precisely 6.23pm on 26 September 2016 and connected Aleixo (and Granatyr who was with him) to an individual known as 'Sandro'. As the transcripts included in the two lawsuits later filed by Paraná's Prosecutor's Office suggest, the tone of the call was friendly and hints that a previous conversation may have already taken place between Aleixo and Sandro.

Court documents identify 'Sandro' as a person named Alessandro Faria, the manager of Masterpiso (also registered under the name of Compensados Império), an Indusparquet subsidiary based in the state of Paraná.

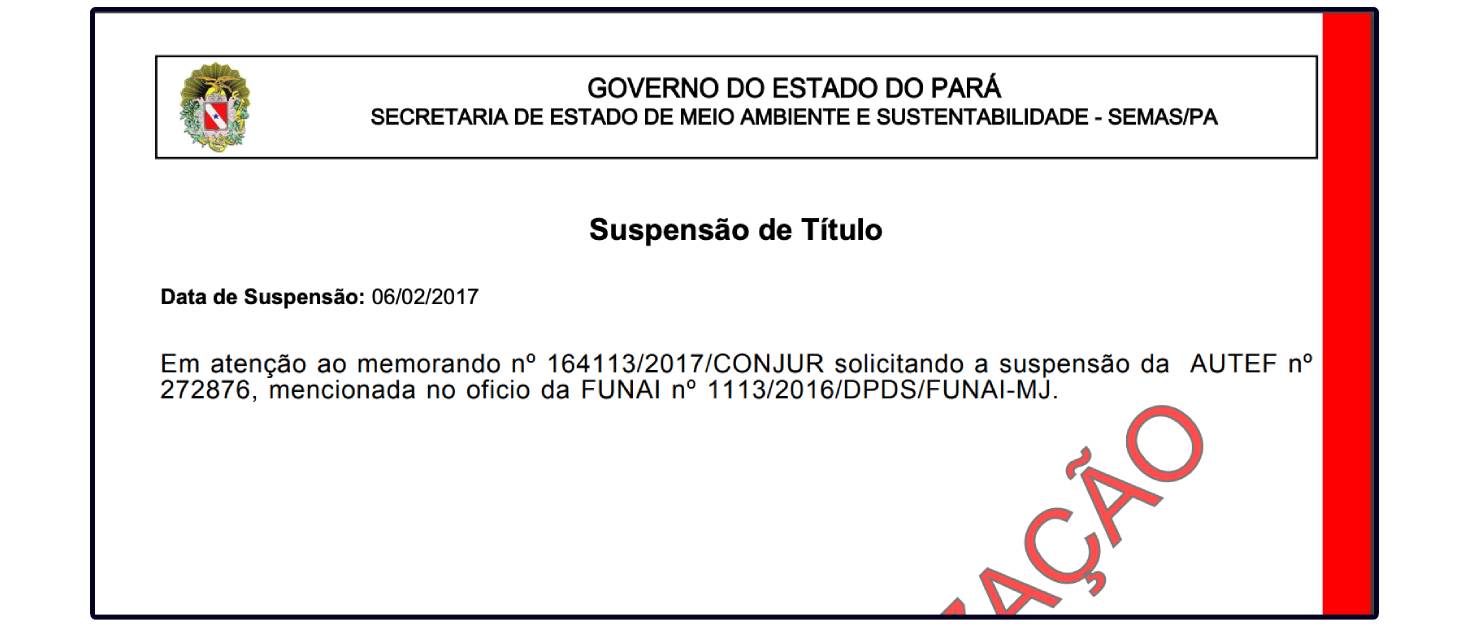

The matter under discussion that day was the purchase of bracatinga wood for an 'American client.'

Baggio, as Faria explained, was "a bit desperate" to get 250 cubic metres of bracatinga wood, a species endemic to the particular part of the Atlantic Forest where Aleixo was based, that he wanted delivered immediately.

Holding Faria on the line, Aleixo assertively asks Granatyr, who seemed to be in the same room as him: "Are you able to work if I can find the wood?"

Baggio, as Faria explained, was "a bit desperate" to get 250 cubic metres of bracatinga wood, a species endemic to the Atlantic Forest

Aleixo then turned back to Sandro to confirm that Granatyr had experience of working with bracatinga wood and explained that Granatyr wished for 700 Reais per cubic metre. Aleixo then said: "Actually, I was going to suggest 700 to see if he [Baggio] paid me a small commission, right?" and laughed.

Sandro suggested Aleixo should be more ambitious and charge 750 or 800 Reais so he could have his commission 'guaranteed.' Sandro explained that the sawn wood would be transported to Indusparquet's facilities, where flooring would be produced from it before being exported. They also discussed the production of bracatinga wood laminate, an indication this could be just the beginning of a promising business partnership.

Aleixo asked Granatyr if he had experience with producing laminates and while confirming he did, he told both Granatyr and Sandro he would help to finance Granatyr's sawmill and work as his partner on the production.

Aleixo said: "I'll make a partnership here with Luiz [Granatyr] and join his company".

Aleixo ended the call praising "God's will" for having had the opportunity to meet Granatyr out of the blue.

Snippet of the court document detailing a conversation between André Aleixo and Alessandro Fraria. Source: Paraná State Justice

Snippet of the court document detailing a conversation between André Aleixo and Alessandro Fraria. Source: Paraná State Justice

When the basic parameters of the deal had been discussed, Faria told Aleixo that Baggio himself would take over the negotiations from then on.

It did not take more than a few minutes. At 6.41pm on the same day, 26 September 2016, less than 20 minutes after the call with Faria, Baggio called Aleixo's mobile phone and was greeted as "my friend", an indication again that this may not have been the first conversation between these two men.

The man on the call, José Antonio Baggio, was none other than the co-founder of Indusparquet, veteran of the Brazilian timber industry of more than four decades. As teenagers, Baggio and his partner, cousin Luis Francisco "Kiko" Uliana would reportedly make parquet flooring in the week and install it for clients on the weekends.3 Since they founded the company in the 70s they had built relationships with a wide network of suppliers in Brazil4, with Baggio playing the primary role in handling wood purchases.5 It seemed clear that despite the company's considerable workforce (reportedly around 500 employees), Baggio was not above taking a personal hand in the running of his business, even at the lowest levels.

Aleixo was eager to brief Baggio about his meeting with Granatyr, but soon realised that it was neither fortuitous circumstance nor the will of the almighty that had put the sawmill owner in his path. In fact, it was Baggio himself who suggested that Granatyr should seek out Aleixo at the rally earlier that month. This wasn't a match made by God, it turned out, but one made by an experienced timber trader in the regular course of his business.

"I asked him [Granatyr] to speak to you," Baggio told Aleixo. Baggio then explained "We have already agreed. He will saw the wood, we just need you to sort things out."

Indusparquet founders Luiz Francisco "Kiko" Uliana (right) and Jose Baggio (left). Source: Julio Vilela

Indusparquet founders Luiz Francisco "Kiko" Uliana (right) and Jose Baggio (left). Source: Julio Vilela

Prosecutor Juliana Mitsue Botomé asserts that to "sort things out" meant that Aleixo's role would be to identify rural producers of bracatinga in the region, who would need logging permits to cut the wood. And at the time, these permits just happened to be handed out to loggers by the very same agency Aleixo had a leading role at.6

Why else would Baggio tell Granatyr to look for the defendant André Aleixo? According to Botomé, "Obviously because the defendant José Antonio Baggio had full confidence that the defendant André Luis Aleixo had the necessary tools and knowledge to facilitate the acquisition of the wood, which could only be justified on the grounds of the public office he held".7

Another clue that using his position to sort out the required permits was expected to be Aleixo's role comes later in the conversation between Baggio and Aleixo. Aleixo tells Baggio that if Granatyr's challenge was to get the wood, he could help find someone producing bracatinga. Baggio had no time to lose and took it as a done deal.

Wire-tapped calls

After being tipped off about the court case that resulted from the sting by an anonymous source, Earthsight and Mongabay secured access to and analysed in detail more than four hours of footage, detailed witness testimony and timber transport documents from the court hearings in the civil case, plus additional transport documents obtained through freedom of information requests. This has allowed us to gain unprecedented insight into the negotiations between Indusparquet and one of its local suppliers, revealed here for the first time.

During the 43-day period between 26 September and 8 November 2016, dozens more conversations were intercepted revealing the progress of negotiations between defendants Aleixo, Baggio, Granatyr and Alexandre Puzyna, an individual brought into the scheme by Aleixo to act as an intermediary in the negotiations.

More than 30 extracts from these tapped calls would eventually be included in two cases – one civil and one criminal – filed by the state prosecutor as part of the corruption allegations. In the civil lawsuit, Aleixo, Baggio, Granatyr and Puzyna were charged with administrative improbity, defined as wilful and conscious action perpetrated by a public agent or benefiting non-public agents.8

The prosecutor also calls for Indusparquet and Granatyr to be punished under provisions of Brazil's anti-bribery law, the so-called Clean Company Act

The civil case was filed under sections of a law9 on public civil actions targeted at violations of collective interests such as the environment, consumers or cultural heritage and sections of the Brazilian Administrative Improbity Law which regulates10 the illicit enrichment of public officials. The prosecutor also calls for Indusparquet and Granatyr to be punished under provisions of Brazil's anti-bribery law, the so-called Clean Company Act.11

The criminal case meanwhile had all the elements of a classic bribery lawsuit. Aleixo was charged with illicit enrichment while in public office and Baggio was charged with offering a kickback to a public official in return for privileged information on wood suppliers with the right permits to supply it.12 Puzyna and Granatyr were also charged for their role in the alleged scheme.

In the criminal case, Baggio, Puzyna, Granatyr and Aleixo were all acquitted at first instance, and the decision was upheld following a ruling in August 2022. However, prosecutors say the case is not yet over, since they are currently seeking avenues for a further appeal. A civil case against him and his company remains ongoing. As detailed throughout this chapter, the hours of recorded telephone conversations were relied on in both the criminal and civil Paraná cases relating to the same alleged corruption scheme.

Although Alessandro 'Sandro' Faria, who set up the initial connection between Aleixo and Baggio, wasn't charged, he is intricately connected to the Indusparquet family as the son-in-law of Kiko Uliana, Baggio's cousin, and the other founder of Indusparquet. There is no suggestion that 'Sandro' had knowledge of any alleged corrupt scheme.

Alessandro Faria (middle) and Indusparquet co-owner Luiz Francisco Uliana (far right) promoting Masterpiso Engineered Floor in an event in Curitiba. Source: Raquel Lima

Alessandro Faria (middle) and Indusparquet co-owner Luiz Francisco Uliana (far right) promoting Masterpiso Engineered Floor in an event in Curitiba. Source: Raquel Lima

Baggio was recorded speaking to Aleixo twice by investigators, but his name is mentioned several times in the evidence filed by the Prosecutor, not only by Aleixo but also by the sawmill owner Granatyr, who became Baggio's main point of contact during the negotiations.

On October 7th 2016, for example, the sawmill owner tells Aleixo: "They are in a hurry, this week alone they called me three times. […] I told Zé Antonio [Baggio] that they can close a deal."13

A few weeks later, on October 25, Granatyr tells Aleixo that he was expecting to receive another call from Baggio, who was worried about the deadline for the lumber delivery: "Zé Antonio [Baggio] will certainly call me today… they had called me last Thursday."14

"Of course, this is logical. You can work as our representative in the region, because I hope we sell a lot of this wood"

In both the criminal and civil lawsuits, prosecutor Botomé asserts that Aleixo committed himself to guaranteeing the supply of wood for the sawmill for a commission, wood that would later be sold to Indusparquet.

According to the Public Prosecutor of Paraná's civil case, the payment of a 'commission' was requested and promised as part of the negotiations. In the call with Faria, as mentioned earlier, while discussing the price of wood, Aleixo had asked if he would be paid for his service. However, the promise was not just about a commission, but something even bigger.

The wiretaps revealed that Baggio also suggested that Aleixo could work as his agent in the region. In a conversation recorded on 29 September 2016, at 8.46am, after Aleixo's request for an email detailing his commission, Baggio replied, "Of course, this is logical. You can work as our representative in the region, because I hope we sell a lot of this wood".15

Pulling out all the stops

The investigation indicates that to meet timber giant Indusparquet's demand, Aleixo was ready to risk committing potentially illegal acts. He was the regional head of the environmental office in União da Vitória, an agency responsible for handing out forest permits and could not use this to benefit private interests. Intermediating in the commercial negotiations between lumber companies for a fee would be a conflict of interest. This might explain why Aleixo decided to bring Alexandre Puzyna into the talks.

The probe suggests that Puzyna was tasked with buying and transporting the wood from the rural producer to Granatyr's sawmill, while Aleixo would act behind the scenes, seemingly to avoid the risk of being discovered. At least, that is what he may have hoped.

On September 28 2016, Aleixo tells Granatyr: "Let's do the following, even if you find the guy who has the authorisation [logging permit], let's pass it on to Puzyna, I prefer that each one takes care of his own line."16

André Aleixo in 2016, when head of IAP regional office in União da Vitória. Source: Marciel Borges

André Aleixo in 2016, when head of IAP regional office in União da Vitória. Source: Marciel Borges

Aleixo had another major problem to be solved: obtaining the right authorisation for Granatyr's sawmill to receive and process the bracatinga. Although he did not have access to Sinaflor, Ibama's electronic system that monitors the exploitation and trade of timber, the wiretaps identified conversations that indicated that Aleixo was asking his co-workers to help him cut the red tape involved with obtaining the permit.

On one occasion, Aleixo even travelled with some documents to Curitiba, Paraná's capital, where the Environmental Institute's headquarters are located. On October 25 he tells Granatyr. "I am going to Curitiba tomorrow. […] I'll ask [him] to do it tomorrow, because now it's all done in Curitiba, so I'll be there tomorrow and then he'll get it fixed."17,18

While still waiting for the permit that would allow Granatyr to store and process bracatinga wood, the group contacted a rural producer in the region through a connection from Aleixo. The attempt, however, was fruitless, as investigations reveal. They concluded that the timber this contact could provide wasn't thick enough to be sawn. The trees were just too young.

Indusparquet's Brazilian website features flooring made with bracatinga (also known as Amendôla). Source: Indusparquet SC

Indusparquet's Brazilian website features flooring made with bracatinga (also known as Amendôla). Source: Indusparquet SC

The problem of a permit for Granatyr's mill was finally resolved in early November and, a few days later, they managed to find another rural producer who was ready to sell them bracatinga.

Despite seemingly trying to keep a low profile in the negotiations, Aleixo was up to his neck in discussions about how the timber would be sourced and transported, even using his own office during working hours to meet with Puzyna and Granatyr and discuss the deal, the evidence suggests. He had travelled to Curitiba in an apparent attempt to help Granatyr’s sawmill get the right permits. On one occasion, he was even recorded asking for details about the lorry used to get the wood to Granatyr’s sawmill. “Do you have the lorry’s plate [license plate]?”, he asks Puzyna on 07 November 2016.

Meanwhile an anxious Baggio continued to push for the process to be speeded up.

"He needs it because the timber he has there is not enough for him to do what was agreed with his client. He is worried."

In a conversation between Granatyr and Aleixo the following day, Granatyr said, "Zé Antonio [Baggio] called me, it was not even eight o'clock, to give you an idea [...] He needs it because the timber he has there is not enough for him to do what was agreed with his client. He is worried."19

This was, in fact, one of the last conversations that investigators intercepted.

To learn whether Indusparquet was able to seal the deal, Earthsight and Mongabay obtained the receipts and DOFs20 (timber transport permits) issued to both the rural producer and the company that transported the timber through an information request. They reveal that the coveted bracatinga logs finally reached Granatyr's mill on December 2nd 2016.21

Five shipments then left Granatyr's sawmill for Indusparquet's headquarters in Tietê, São Paulo. They took place between December 2016 and March 2017 and totalled 35.64 cubic metres, a much smaller volume than the original 250 cubic metres discussed in the talks recorded in September that year.22

It is unclear how Baggio or Indusparquet felt about such a long and confusing negotiation. What was clear however is that by now, far from a match made in heaven, what was hoped to be a simple deal had not only failed to deliver all the goods, but had dragged, and would continue to drag, everyone concerned through hell.

From the horse's mouth

Baggio, in testimony given in 2017 during the civil proceedings, at first maintained that he did not remember any conversation with Granatyr and did not know and had never heard of anyone named Aleixo. However, just last year on 5 November 2021, something appears to have changed his mind and he was finally persuaded to appear in court to give a rather different account.

Regarding contact with Aleixo, Baggio admitted he had indeed called him asking for bracatinga and offering him the role of 'regional buyer,' contradicting his 2017 testimony. He claimed they stopped talking a few days later when he realised that no-one in the sector knew Aleixo. Baggio categorically denied knowing that Aleixo was a civil servant.

"We know very well, we have dealt with Ibama for a long time now, we follow the rules, a civil servant can never do that. We were ignorant of the fact he was a civil servant."23

Contradicting the 2016 wiretaps which indicated that Baggio had asked Granatyr to seek out Aleixo, Baggio testified that he did not know that Aleixo and Granatyr were even working together.

"I spoke with Luiz [Granatyr] to send me timber but I was not aware of the connection between the two of them."24

Curiously, no-one in the company seems to have done a simple internet search for Aleixo's name. Several websites carry information about Aleixo's appointment as head of the local environmental agency

He even tried to claim that the purchases of wood from Granatyr had taken place a few months before he talked to Aleixo, contradicting not only the recordings but also DOFs and receipts issued for the shipments of bracatinga from Granatyr to Indusparquet, dated from December 2016 to March 2017, after the wiretaps between Baggio and Aleixo discussing the deal.25

At the remote hearing that happened by video call in November 2021, Baggio appeared relaxed and comfortable. He informed the hearing that his company was planning to expand operations in Paraná: "We're going to open a factory now in Irati, which seems to be Judge Emerson’s hometown26, isn't it?"

The Judge confirmed this by nodding his head and a thumbs up. That Baggio should know where the Judge grew up is unremarkable. That he should mention Indusparquet's investment in that town during the proceedings raises obvious questions about what the defendant may have been trying to achieve by referring to his company's expansion in this context.

There is no suggestion that this exchange indicates any inappropriate relationship or corrupt influence of Judge Spak by Baggio and Indusparquet rejects any such insinuation as "absurd".

The long delays in the case seemed to be part of Baggio's defence team's plan, engineered so that the statute of limitations would expire. They persuaded Indusparquet employees and three of its suppliers to testify in Baggio's favour but the time taken to locate them from different states and elicit their statements prolonged the hearings even further.

Apart from the long delays, the strategy devised by the company's defence team in the civil case appeared to be centred on three points: highlighting how customary it is to ask for a commission in timber transactions; the informality with which Baggio is known and treated by Indusparquet's suppliers and finally, the fact that the company was unaware that Aleixo worked for the Paraná environmental agency.

This last point, in fact, was a topic exhaustively addressed by the witnesses, who emphasised how Indusparquet had tried to find out more about Aleixo. Curiously, no one in the company seems to have done a simple internet search for Aleixo's name. Several websites carry information about Aleixo's appointment as head of the local environmental agency and some of the activities he took part in while in office.27

Baggio's hearing. Pictured are (clockwise from top left) Baggio, prosecutor Botomé, Aleixo, and judge Emerson. Source: Paraná State Justice

Baggio's hearing. Pictured are (clockwise from top left) Baggio, prosecutor Botomé, Aleixo, and judge Emerson. Source: Paraná State Justice

Three of the witnesses called by the defence to testify were loyal timber traders who have worked with Indusparquet for decades, according to their own account. All three uncannily parroted the same narrative, in the same sequence, a strong indication they may have been coached.

The timber traders claimed:

1. Baggio had contacted them asking if they were able to supply bracatinga timber

2. They all said they did not work with this wood

3. Sometime later, Baggio made contact again, this time to ask if they were acquainted with someone by the name of André Aleixo

4. They all said no, but offered to contact other timber traders and ask about Aleixo

5. They spoke once more after this, when they said that nobody had ever heard of this name before.28,29

The statements also tried to play down some of the other details highlighted by the lawsuits. They said that Baggio, despite being one of the owners of the largest flooring manufacturers in the country, was very accessible to all suppliers and spoke to them directly, usually being called "my boss" or "my friend".30

Meanwhile the three Indusparquet employees were eager to defend their boss. They all stated how common it is to discuss a commission on the first phone call, and repeated almost verbatim descriptions about how each of them received up to 30 calls a day from prospective suppliers, a very specific number which is another clue that they may have been coached with some guidelines moments before their hearings.31

Two and a half years had passed since Indusparquet's defence first made a request to call these witnesses in 2018, many located out of town – creating more legal complications – and the interrogation of the final witness, who testified in early 2021.

BRAZIL'S ATLANTIC FOREST: PROTECTING WHAT'S LEFT

"Brazil is seen as a huge Amazônia," environmentalist Mario Mantovani told Earthsight and Mongabay.

But along Brazil's south coast and inland areas, the Atlantic Forest, or Mata Atlântica, has become one of the country's most threatened forests.

Click here to read more

On the defendants' side,39 Aleixo denied asking for a commission or working as a consultant for Granatyr even though dialogues recorded by the investigators suggest the exact opposite. He claimed that he had planned to leave the environmental agency in early 2017, although this is irrelevant since the negotiations occurred while he was still in office. He stated he had decided to contact Indusparquet's subsidiary as part of an exercise of what he might do next.

He denied using his position to speed up the granting of the permit to store and process bracatinga wood at Granatyr's timber yard and explained that he decided to exit negotiations when he realised that Baggio was demanding a huge amount of wood to be delivered while he was still in office, contradicting evidence from the wiretaps.

In the civil case, Indusparquet's apparent efforts to delay the process seem to have borne fruit, as a judge sought to dismiss the case in May 2022 on the basis that the statute of limitations had passed. Prosecutors have appealed this decision. The case is ongoing.

Baggio still has a prominent role at Indusparquet

In the criminal case, judge Emerson Spak absolved Baggio, Aleixo, Puzyna and Granatyr of all corruption charges. He stated that the advantage promised (commission) was merely intended to remunerate Aleixo for a lawful service rendered in the context of private relations with Indusparquet and did not constitute a wrongful act.

Prosecutor Botomé appealed the decision, saying it violated commonly understood definitions of illicit enrichment by the Federal Supreme Court40 and that Aleixo's parallel activities were incompatible with his status as a public official.

In August 2022 her appeal was dismissed by the judges of the second criminal court in Paraná by unanimous vote. They said there was not enough evidence to prove a causal link between the advantage offered to Aleixo and the provision of privileged information to Baggio by him. However, sources in the prosecutor's office in Paraná, that Earthsight and Mongabay spoke to, say the case is not yet over, since they are currently seeking avenues for a further appeal.

Aleixo was removed from office in early 2017 following unrelated corruption allegations

In response to our allegations, Indusparquet states that Mr Baggio was cleared both in the trial court and court of appeal for the criminal lawsuit, and that the court of appeal ruling of the first instance, i.e. that of Judge Spak, was confirmed by a unanimous decision. Further, Indusparquet states that the court recordings "simply confirm a regular negotiation, with common language and tone, where prices, measures and sales commissions are discussed." They said that at no point did Aleixo identify himself as a public official and that Baggio and Faria only became aware of his position subsequently.

Aleixo, approached for comment, told Earthsight and Mongabay that the allegations of the Public Prosecutor's Office were "unfounded" and "cannot succeed." He stated that he had been cleared of criminal charges, a decision that was upheld on appeal, and that the civil case was dismissed in the first instance. With regard to the judicial decisions, he stated that we should "move forward, with the direction and provision of God."

Puzyna told Earthsight and Mongabay that he had not purchased and did not transport any bracatinga logs to Granatyr's sawmill. He pointed to the fact that the receipts and timber transport permits (DOFs) did not mention his name anywhere as proof of this. He stated that the public prosecutor's office had mistakenly filed a criminal complaint that was ruled totally unfounded by the judge in the first degree (Spak) and that this decision was upheld on appeal.

Earthsight and Mongabay spoke to local experts about the broader context of the Paraná cases in Summer 2022, and the situation with enforcement relating to logging and timber licensing in the area's forests. Mario Mantovani, head of an NGO that works to protect the Atlantic Forest, SOS Mata Atlântica, said in a phone interview that Paraná had "lost total control" over environmental enforcement. According to him, the region around União da Vitória – where the activity in the cases took place, has the highest deforestation rate in the state. "And what they did was dismantle the environmental agency… No more supervision. There is nothing else."

We spoke to Renato Morgado from Transparency International Brazil, who told us of the difficulty of prosecuting corruption cases in Brazil. As seen earlier, the lengthy time required to interview various witnesses in the Paraná civil case led to its dismissal on the grounds that the limitations period had lapsed. In October 2021, Brazil enacted changes to reduce the period of limitations for administrative improbity from eight to four years. Without that retrograde change, the civil case would have been able to freely run its course.

Referring to these changes, Morgado said, "What we are actually experiencing is a time of setbacks in the legal and institutional anti-corruption framework. This is happening very quickly. These setbacks clearly give a signal that corruption will be tolerated and not punished. This makes private and public agents more willing to commit acts of corruption."

In the meantime, life goes on in Brazil. Baggio still has a prominent role at Indusparquet and was recently giving interviews about the value of certification and the importance of tracking the origins of timber.41

Aleixo, who was removed from office in early 2017 following unrelated corruption allegations42, was invited to work for the state government again, this time as regional head of Paraná Secretariat of Justice, Family and Work.43 He spent almost two years in this role before leaving it and now has an office in União da Vitória, where he works as a self-employed lawyer defending – among other clients – those charged with environmental crimes.44

Our Man in São Paulo

Bribes in Bauru

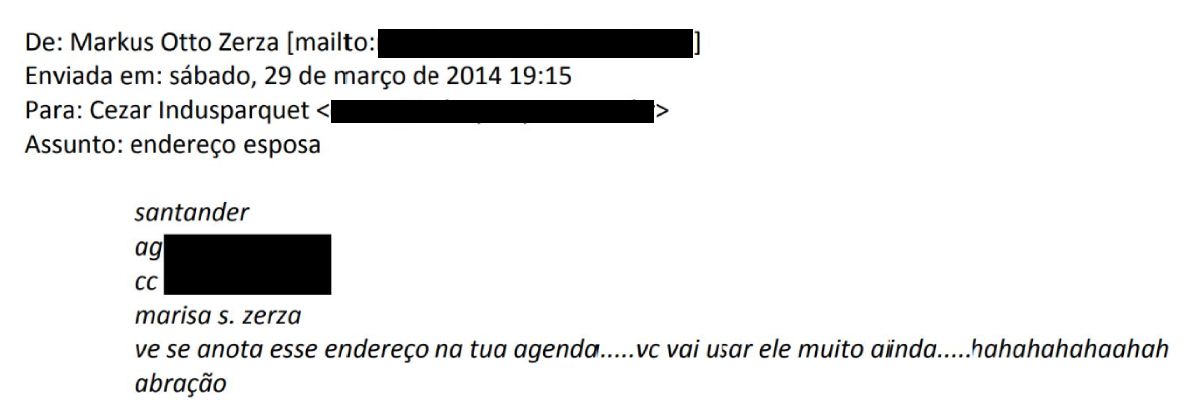

Despite a long week at the office, Markus Otto Zerza, an analyst at Brazil's environmental agency, Ibama, was in a playful mood as he answered emails late one Saturday afternoon.45

The 56-year-old had worked at Ibama for more than a decade, most recently for the federal agency's Advanced Unit in Bauru, a city in the southeastern state of São Paulo. The work was not glamorous. But it earned Zerza a decent salary46, enough to keep him and his wife Marisa, a nurse one year his senior, and their son in their house in a residential neighbourhood in Bauru.

Yet Zerza wanted more. That evening, in a breezy message from one of his two personal email accounts47, he sought a little extra work, and shared Marisa's bank details with someone.

"See if you write down this address in your diary..." he wrote in the email, sent at 7.15pm local time on 29 March 2014, "you will use it a lot yet... hahahahahaahah [sic]"48

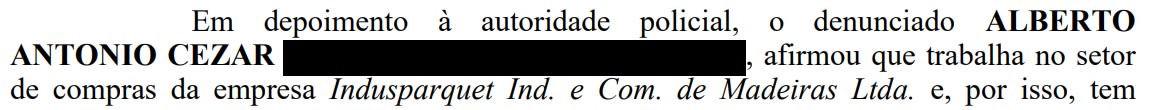

So it proved. The email he sent was to Alberto Antonio Cezar, a long-term employee at Brazil's largest flooring company Indusparquet, with connections to the firm's owners, as court records reveal.

With his man inside the Ibama system, Cezar, who is 6449, could rig the market in his paymaster's favour. Zerza, who later admitted to receiving bribes from Cezar, played this role with relish. Together the pair embarked on what is alleged to be a lucrative and highly illegal scheme which lasted for many years and embroiled Indusparquet and a tight cartel of business partners in its web.

Zerza shared his wife's bank account details with Cezar in an email on 29 March 2014, joking that the Indusparquet employee would use them "a lot". Source: Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Zerza shared his wife's bank account details with Cezar in an email on 29 March 2014, joking that the Indusparquet employee would use them "a lot". Source: Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Documents unearthed by Earthsight and the environmental news website Mongabay including court files, police reports and email transcripts, contain evidence of Indusparquet's deep complicity in the allegedly corrupt dealings.

They expose how the firm profited handsomely from illegally bypassing rules meant to protect climate-critical forests.

Photo of Markus Otto Zerza and wife Marisa in a Federal Police file obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Photo of Markus Otto Zerza and wife Marisa in a Federal Police file obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

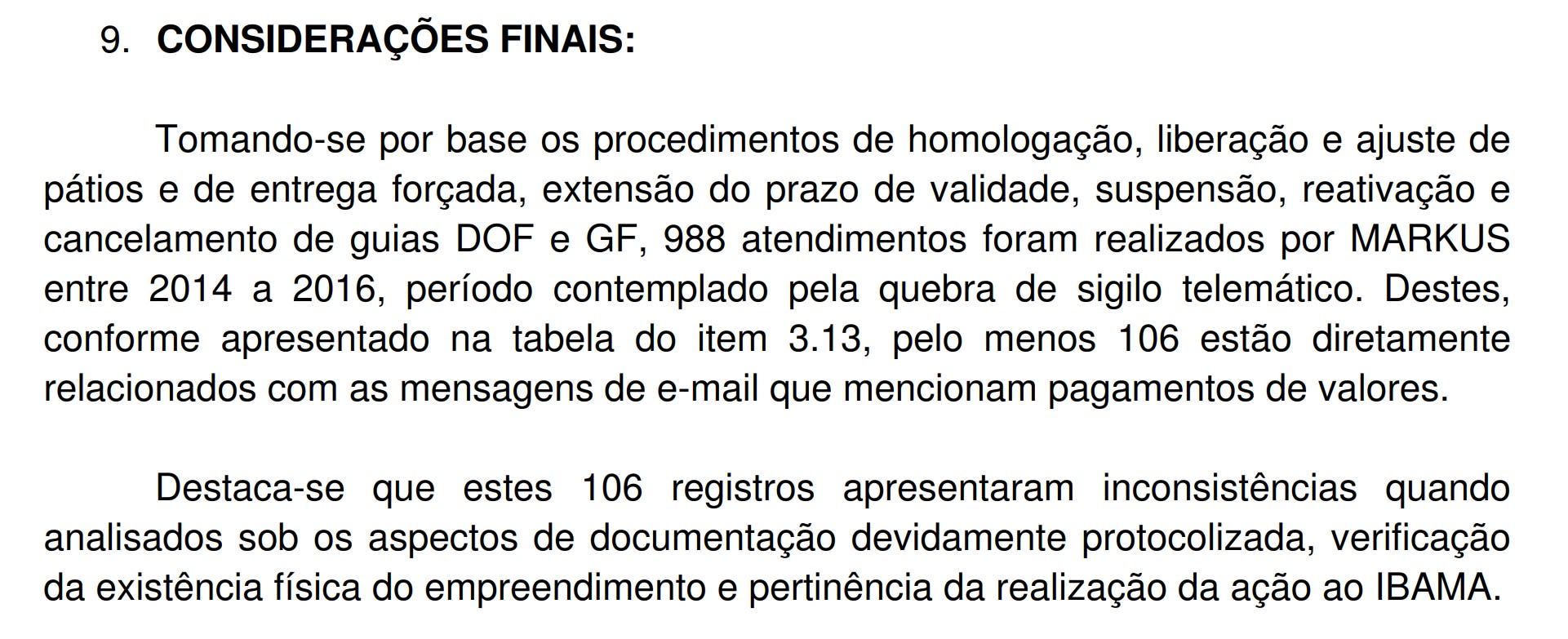

Cezar flooded the Ibama employee with requests, month after month, year after year. According to the prosecutor's filed statement, between 2014 and 2016 alone, the Ibama official performed at least 988 favours not only for Cezar's company Indusparquet but for many other "partners", including asking that "suspended yards" – timber seized by Zerza's own agency for violations of the rules – be released, or for timber stocks to be added, adjusted or their validity period and other parameters changed.50

The prosecution further directly linked more than 100 of these tasks to emails mentioning the payment of bribes.51,52 Despite the explosive evidence, investigators believe the money trail exposed is just the tip of the iceberg.

Recap

Operation Patio, a crackdown on fraudulent timber practices that had been long prevalent in Brazil, started strongly. Launched in May 2016, the joint investigation by Ibama and the country's Federal Police resulted in what the former described as the largest seizure of "illegal Amazon timber" in São Paulo state's history.

The haul worth $2.5 million came from Indusparquet. Accused of various illegal practices, the flooring giant received fines totalling R$995,762 ($259,030 at the time) and was temporarily banned from trading timber.53,54 Then the political winds changed.

Indusparquet's headquarters in Tietê, São Paulo. Source: Earthsight

Indusparquet's headquarters in Tietê, São Paulo. Source: Earthsight

Earthsight previously reported how Ibama had first prompted Operation Patio by approaching the Federal Police in May 2016 with concerns that an agency employee was engaged in laundering timber.55 The resulting two-year probe took its name from the Portuguese term for the courtyard, or yard, used to store wood.

The Operation not only led to the record seizure in late May 2018, goods that Ibama said had not been accompanied by the necessary permits, but also uncovered an alleged fraud scheme that may have allowed Indusparquet to hide illegally-harvested timber among legal stocks.56

Ibama officials inspect an Indusparquet facility during Operation Patio. Photo: Ibama

Ibama officials inspect an Indusparquet facility during Operation Patio. Photo: Ibama

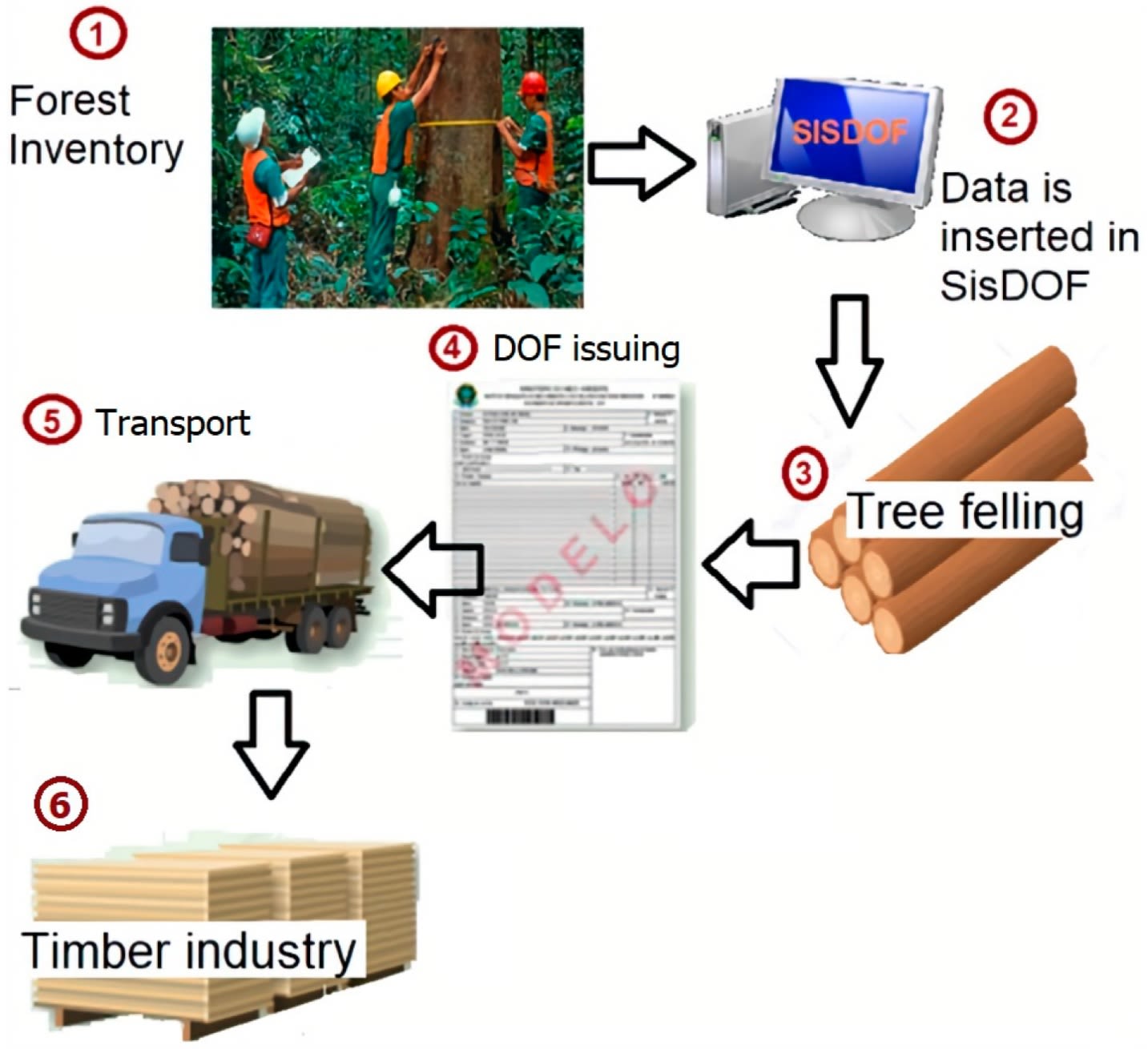

Ibama's electronic system Sinaflor/SisDOF57 is supposed to keep a close eye on logging and timber trading across Brazil. It operates in a similar way to how money moves between bank accounts, allocating virtual credits to forest concession holders detailing the species and volume of wood authorised to be cut, tokens that pass to whoever buys the goods.

By law, each transaction must be accompanied by a document of origin, or DOF, attesting to the wood's origin and legality. Moving or holding wood without the proper papers or credits is illegal. Given the difficulties of policing its vast forests at source, this system is the country's most important tool for trying to deter illegal logging. It is intended – in theory at least – to prevent illegal wood from being traded and sold, and thereby eliminating any incentive to cut it in the first place.

How Brazil's timber trade is supposed to work. Source: Perazzoni et al., 2020

How Brazil's timber trade is supposed to work. Source: Perazzoni et al., 2020

In the Indusparquet case, Ibama initially reported it had uncovered 10,740 cubic metres of fictitious timber credits – a serious breach of Brazilian law. The flooring giant's main warehouse in Tietê, São Paulo was temporarily banned from trading timber, and more fines followed.

But, as Earthsight later revealed, Indusparquet's largest fine was cancelled and its confiscated timber returned under strange circumstances in June 2019.58 The U-turn, branded "shameful" by Elisabeth Uema, the head of a national association representing environmental civil servants, was one of countless instances of Ibama officials appointed by the administration of president Jair Bolsonaro, who took office in January of that year, apparently undermining efforts to enforce environmental laws.

Indusparquet's largest fine was cancelled and its confiscated timber returned under strange circumstances

However, Indusparquet remained under scrutiny. Elsewhere in the state of São Paulo, a federal prosecutor was connecting the dots between the flooring giant, its man in São Paulo, and his lapdog inside the system.

Credit cartel

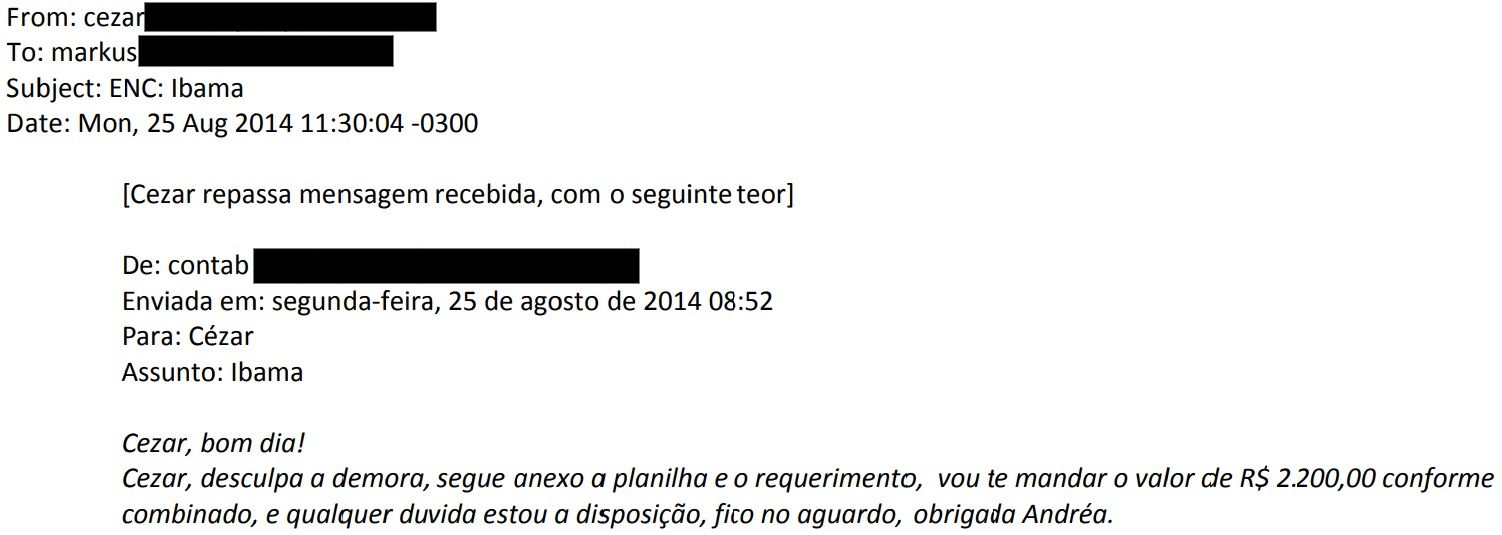

Federal prosecutor Pedro Antonio de Oliveira Machado eventually filed a civil lawsuit in Bauru in late March 2021 against Indusparquet and six firms that it did business with to follow up on the findings unearthed by Operation Patio.59 Earthsight and Mongabay obtained a copy, together with a cache of court files that show that Zerza and Cezar had indeed been busy.

Listed alongside Indusparquet as co-defendants are the companies Baurupisos, Thais Cristina Teixeira Brasil, Ulimax Esquadrias de Madeira, Indústria Madeireira Uliana, Demarchi & Co, and Faurtil Fábrica de Urnas Tietê (also called Jonacir Amorim).

Prosecutor Machado has also filed criminal charges against Zerza and Cezar for bribery. Both civil and criminal proceedings remain ongoing.

Cezar confirmed he worked for Indusparquet when questioned by police, according to a Federal Prosecutor's Office document obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Cezar confirmed he worked for Indusparquet when questioned by police, according to a Federal Prosecutor's Office document obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Drawing on hundreds of pages of Federal Police records generated under Operation Patio, the prosecution alleges that these firms got Zerza, the Ibama employee, to manipulate the Sinaflor timber credits system "in a totally unlawful manner".60

These documents are central to the prosecution's case. They show the Ibama official requested and received bribes to perform these services from Indusparquet employee Cezar, who was charged with serving as the middleman between the Ibama employee and the companies.

When questioned by police, Cezar confirmed he worked in Indusparquet's purchasing department,61 while court filings allege that he also worked as a kind of fixer, or environmental advisor/consultant for the other defendants.62,63 According to Machado, there is evidence that Cezar specialised in resolving "DOF blocks", or helping timber move through the market.64

Court filings show Cezar also worked as a kind of fixer, or environmental advisor/consultant for the other defendants

Through the Indusparquet staffer, the flooring giant's business partners are charged with having sought to grease the wheels of Ibama's timber credits system to their commercial advantage. Despite his apparent lowly official role, Cezar, with his network of contacts at public bodies65, is charged with acting on Indusparquet's behalf throughout this process – and to its benefit.

Returning seized wood, releasing timber stocks for trade, "adjusting" a company's credits, among other requests – he is alleged to have left his agency's database awash with "false and improper data".66

Ibama identified at least 106 services performed by Zerza between 2014 and 2016 that were "directly related" to emails mentioning bribes

Ibama identified at least 106 services performed by Zerza between 2014 and 2016 that were "directly related" to emails mentioning bribes, according to an internal report contained in the court files and dated 2017.67 Further analysis by the environmental agency revealed "inconsistencies" in all of these records, the report adds.68

As the Ibama report points out, this was probably just the tip of the iceberg, as many more transactions likely took place. Email correspondence became less frequent over the period studied, leading the agency to assume that other means of communication – it cited Skype and the encrypted messaging application WhatsApp – became the go-to tools for conducting business.

Excerpt from internal Ibama report linking services performed by Zerza between to emails mentioning bribes. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Excerpt from internal Ibama report linking services performed by Zerza between to emails mentioning bribes. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Ibama's report drew on emails the police obtained through a Federal Court order, covering messages sent to and from Zerza's two personal email accounts between 2014 and 2016. It ends on a chilling note.

"In 2017, a period not covered by the breach of telematic confidentiality," it says, "69 more calls were made, showing the same inconsistencies, evidencing the continuity of the modus operandi, which persists to the present date."69

Email logs

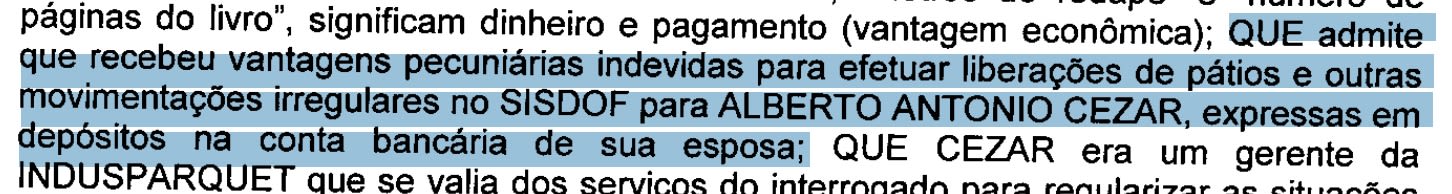

After his and Cezar's arrests in late May 2018, the Ibama employee Zerza admitted to police to receiving bribes through his wife's bank account to facilitate the release and manipulation of timber stocks for Indusparquet employee Cezar.70

He also confessed to gaming the system long after he should have lost access to Sinaflor in late September 2014, when management duties passed to São Paulo state's environmental secretariat.71

The emails uncovered by the Federal Police between the two men formed key evidence in its investigations and, later, in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit.

Ibama official Zerza admitted to receiving bribes to facilitate the release and manipulation of timber stocks for Indusparquet's employee

Prosecutor Machado told Earthsight and Mongabay that if the Federal Police had not gained access to the emails they would only have been able to identify that Zerza "made improper entries in the system, but never that he had received a bribe".72

These candid exchanges, informal and sometimes comic, helped the Federal Police identify five small bank transfers totalling R$2,900 (about $540) from Indusparquet's man Cezar to Zerza's wife's account in 2014 and 2015, the lawsuit states. Officers also found 15 larger transfers totalling R$173,945 (about $34,400) from unidentified sources between 2014 and 2017, which are likely linked to the bribe scheme.

In one court file, the federal prosecutor's office said that "dozens" more payments to Marisa’s account have yet to be traced.73

Zerza admitted to police to receiving bribes through his wife Marisa's bank account to facilitate the release and manipulation of timber stocks for Cezar, according to a Federal Police document obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Zerza admitted to police to receiving bribes through his wife Marisa's bank account to facilitate the release and manipulation of timber stocks for Cezar, according to a Federal Police document obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Meanwhile, under investigation, Cezar denied paying the kickbacks – a brazen move, given Zerza's confession, the money trail leading to his door and the breezy email that kicked everything off, the one in which Zerza sent Cezar his wife's bank details and joked "you will use it [the bank account] a lot yet".

A few months after this message, on 25 August 2014, Cezar had forwarded the Ibama employee a message from Ulimax's accounts department in reply. The Ulimax representative had told Cezar they would send over a spreadsheet and what they described as "the application", as well as transferring an agreed sum of R$2,200 (about US$425).74

Email from Ulimax's accounts department Cezar forwarded to Zerza in August 2014. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Email from Ulimax's accounts department Cezar forwarded to Zerza in August 2014. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

This looked like more smoking-gun evidence of corruption. But Cezar had a creative explanation, telling police he had asked Zerza to buy a used mobile phone in Bauru, where Zerza worked.75 The purchase, he said, was never carried out.76 He did not explain why he had wanted an Ibama employee to buy a second-hand mobile phone at all, or why he had had to pay him to make that purchase.

Correspondence from January 2015 indicates that one of the companies charged in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit, Thais Cristina Teixeira Brasil, wanted Zerza to carry out the illegal release of the company's timber stocks. On 30 January 2015, Cezar forwarded the public servant an email with the subject line "Desbloqueio de pátio" ("Courtyard unblocking"). It contained no text in the message body but four attached image files: three contained the relevant details on the company; the other, the first page of its application to release the stocks.

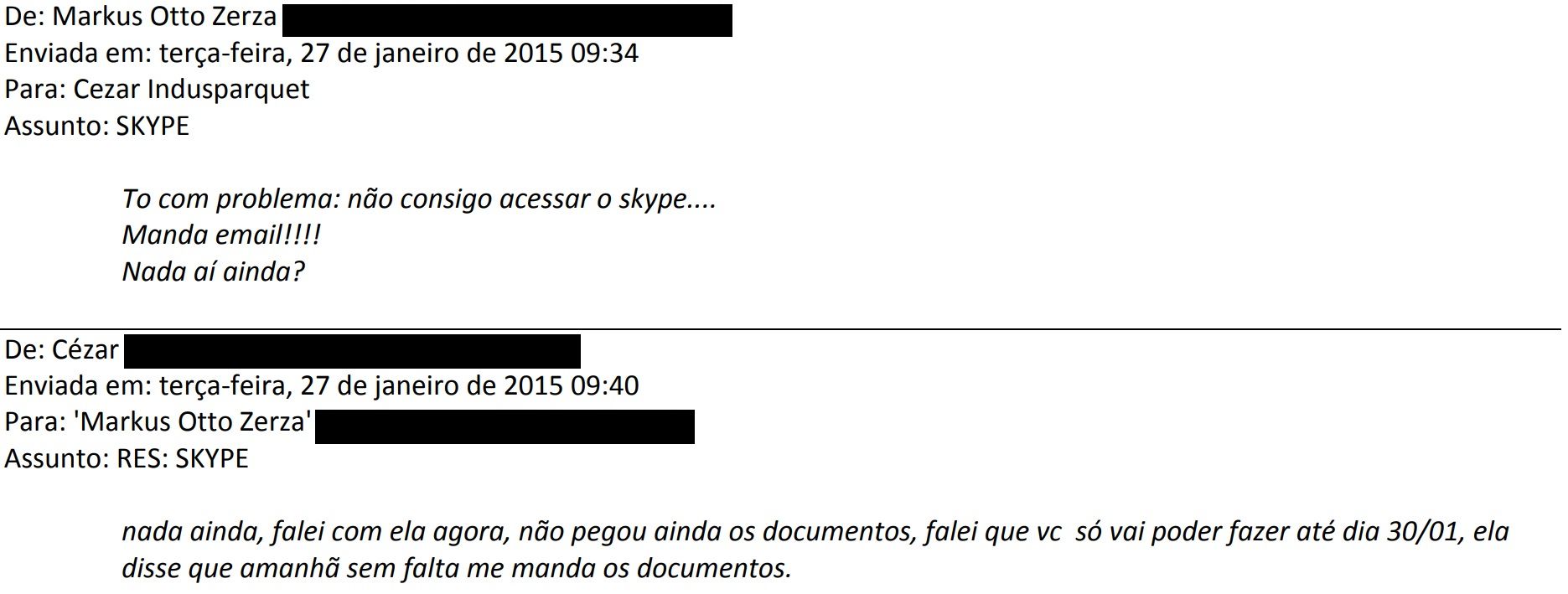

Zerza contacted Cezar early on 27 January of that year, saying Skype didn't work and requesting to talk via email. "Nothing yet?" he asked.77

Email records from January 2015 indicate that one of the companies mentioned in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit, Thais Cristina Teixeira Brasil, wanted Zerza to carry out the illegal release of the company's timber stocks. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Email records from January 2015 indicate that one of the companies mentioned in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit, Thais Cristina Teixeira Brasil, wanted Zerza to carry out the illegal release of the company's timber stocks. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

"Nothing yet," Cezar replied six minutes later. "I talked to her now," he said, referring to the corporate client, adding: "I said that you will only be able to do [the release] until 30/01” – 30 January – "she said she'll send me the documents tomorrow."

Similar emails obtained by Earthsight and Mongabay indicate a consistent pattern: Cezar emails the corrupt official documents to carry out a company's request – his own or another – before charging the firms concerned for this service.78

Indusparquet employee Cezar told Earthsight and Mongabay that he was wrongly targeted by the investigation, which was opened to look into the conduct of an Ibama official. He stated that some of the his messages obtained in the investigation had been interpreted out of context, that neither he nor his company had anything to do with the alleged scheme, and that he will have the opportunity to prove as much to the judge.

Ibama employee Zerza did not respond to requests for comment.

Puppet master

Although Indusparquet is named alongside other companies in the lawsuit, the prosecutor's case is that it masterminded the alleged scheme, and that it stood to gain the most.

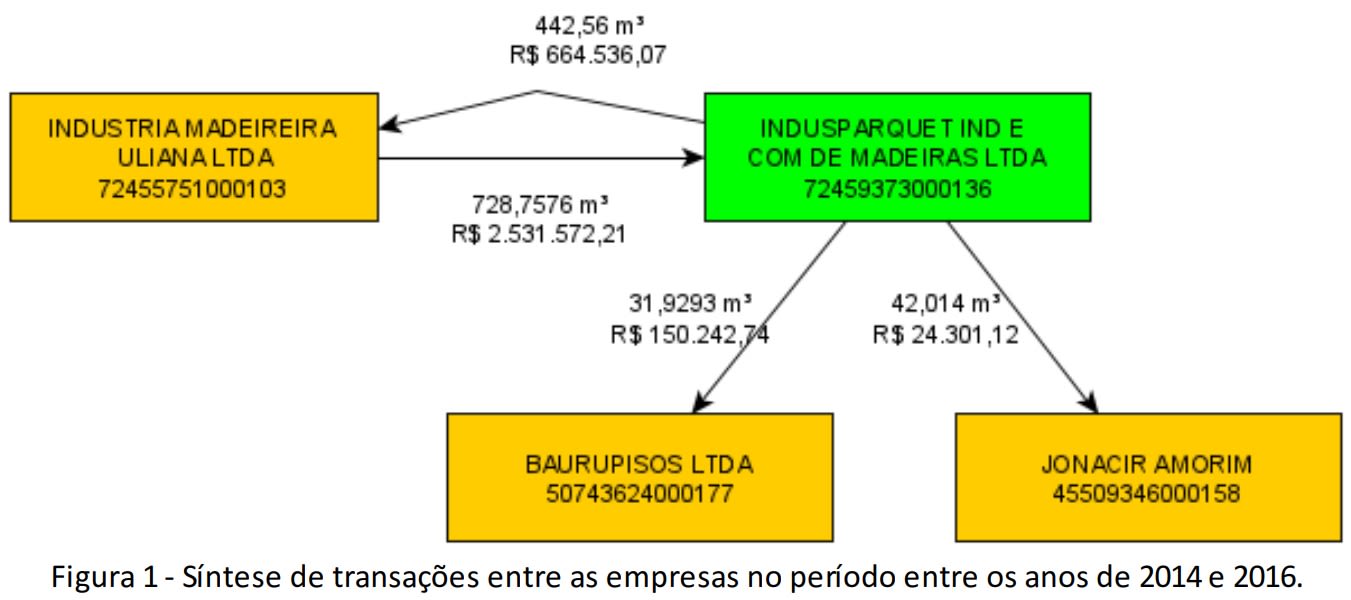

Many of Indusparquet's co-defendants share close ties with it, being owned by members of the Uliana family which co-founded Indusparquet, trading timber with it or functioning as distributors for it.79 The prosecutor states that three of them – Baurupisos, Uliana and Faurtil – "maintained partnerships and/or commercial ties" with Indusparquet.80

In one instance, Ibama official Zerza obligingly "adjusted" Ulimax's timber credits in August 2014, wiping out 1,722 cubic metres of wood from its stocks, according to the prosecution. Two months later, he repeated the favour for Uliana – twice. Another 3,848 cubic metres of wood tampered with.

The prosecutor calculates that Indusparquet derived benefits amounting to R$154,372,773 (equal to almost 30 million USD today)

The prosecutor points to four other firms benefitting when Zerza released timber stocks that had been suspended due to inactivity: Demarchi (which at the time held 297 cubic metres of wood valued at R$575,510), Faurtil (twice, in February 2014 and again in February 2015), Baurupisos (which derived benefits estimated at R$1,636,317) and Thais Cristina Teixeira, in February 2015.81

Cezar's employer, Indusparquet, was alleged to be the biggest beneficiary by far however. On three separate occasions – in June 2014, October 2014 and February 2015 – when the flooring giant was awaiting its new operating licence, Zerza registered "conversion licences" that allowed it to process sawn timber to other products. Case filings analysed by Earthsight assert that to make it even easier for Indusparquet to manipulate the national database to its advantage, during this period the company was allowed access to the DOF system itself, to convert credits from one specific product to another.

The prosecutor calculates that Indusparquet derived benefits amounting to R$154,372,773 (equal to almost 30 million USD today) as a result. From Zerza's first illegal data entry in June 2014 until January 2017, Indusparquet manufactured 19,753 cubic metres of timber credits generated through 591 conversion transactions, nearly double the volume of fictitious credits Ibama agents had initially uncovered during Operation Patio.82

Diagram in a Federal Police document summarising timber trading between Indusparquet and the other firms named in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit from 2014 to 2016. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Diagram in a Federal Police document summarising timber trading between Indusparquet and the other firms named in the federal prosecutor's lawsuit from 2014 to 2016. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Court files also allege that Indusparquet regularly traded timber with its fellow-accused. In a reply to queries from the federal prosecutor's office, Ibama said it had identified 74 transactions between the flooring giant and the other firms mentioned in the legal action from 2014 to 2016.83

For example over this period, the companies exchanged 1,245 cubic metres of wood worth R$3,370,652. Indusparquet supplied 517 cubic metres of the stuff – 443 cubic metres to Uliana, 42 cubic metres to Faurtil and 32 cubic metres to Baurupisos – and received 729 cubic metres worth over R$2.5m from Uliana.84 Considering this only includes what federal investigators were able to track, the real volumes of timber traded between them is likely far higher.

Referring to the flooring giant, the prosecution states: "It should be noted that the defendant does not deny that its proposed agent Alberto Antonio Cezar offered, promised and delivered an undue advantage" – meaning bribes – "to former public servant Zerza, through his wife, so that timber could be released and patios approved in the Sinaflor system for companies that had a commercial relationship/partnership with it".85

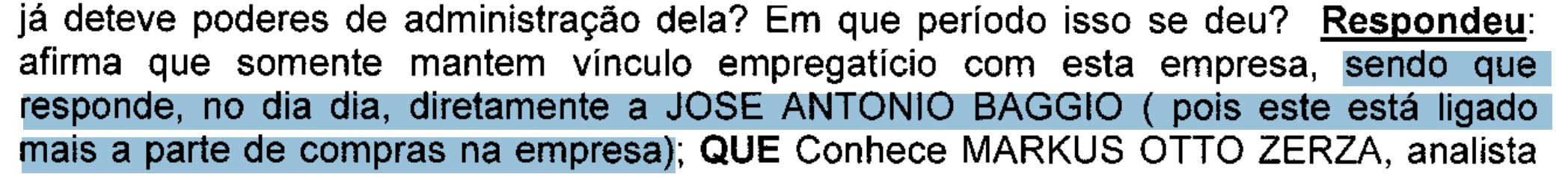

Cezar said he responded "directly" to Baggio on a day-to-day basis, adding that Baggio was "more directly involved in purchases"

When the whole scheme was uncovered, Cezar, Indusparquet's billing clerk, reached out to none other than Indusparquet's co-owner Baggio for help, a curious piece of evidence that may indicate the alleged timber laundering scheme had had sign-off at the highest levels, and had been occurring with the full blessing of its veteran co-founder. Why else would a billings clerk reach out to a person with such a high status in a company with more than 500 employees when arrested?

Taken into custody on 24 May 2018, Cezar, says a Federal Police report, "contacted José Antonio Baggio, director of the company Indusparquet, to communicate about his arrest and to know if the company would appoint a lawyer" for him.86 On a day-to-day basis, he said, he responded "directly" to José Antonio Baggio as the latter was "more directly involved in purchases."87

Taken into custody in May 2018, Cezar, says a Federal Police report, said he responded "directly" to Indusparquet co-founder José Antonio Baggio. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Taken into custody in May 2018, Cezar, says a Federal Police report, said he responded "directly" to Indusparquet co-founder José Antonio Baggio. Source: Federal Police / Federal Prosecutor's Office - São Paulo

Desperate race

Pedro Antonio de Oliveira Machado, the federal prosecutor, now faces a race against time to pursue their case against Indusparquet and its co-defendants.

The civil lawsuit contains damning charges: both active and passive corruption by the parties, fraudulent misrepresentation, and entering fake data into a government database to try to obtain undue benefit. It also argues that their actions damaged public governance by hindering the environmental agency Ibama's ability to enforce the law.

Rumbling alongside it is the still-ongoing police probe. Wary that Brazilian law allows corruption accusations to be thrown out for exceeding the statute of limitations (in this case five years since the first elements were revealed), the prosecutor's office is sifting through hundreds of pages of evidence to file cases in time. The pile grows every 90 days, when updates on the police's enquiries arrive.

If convicted, Indusparquet and its co-defendants would face a major blow. Possible penalties in the civil case include fines of up to one-fifth of the companies' gross revenues, compensation for moral damages, and the loss of goods, rights or benefits obtained through their infractions. They may also face suspension from activities like trading timber, using Ibama's credits system and timber yards for at least two years. They could also be banned from receiving subsidies or loans from public bodies for between one and five years.

In an interview with Earthsight and Mongabay, the prosecutor spoke of another hurdle: a local judge in Bauru's June 2021 order to split the civil suit into multiple cases, a ruling upheld on appeal.

Machado fought on, filing several different criminal and civil lawsuits against the defendants

"This separation will be bad for the public civil action," he said.88 "Why? Because there is a link between these companies: the link is the employee of Indusparquet itself" – alleged fixer Cezar – "and the link is the fact that these companies do business with Indusparquet."

"There is a reason why I left all of them in the same action."

Machado fought on, filing several different criminal and civil lawsuits against the defendants. The initial civil case that forms the subject of this report remains ongoing, although it now lists Indusparquet as the sole defendant. Separate civil lawsuits have been opened against all other companies involved in the alleged timber laundering scheme except Uliana.

Although details of the criminal cases, including the parties named in each, fall under secrecy laws, Ibama ex-employee Zerza, his wife, and Indusparquet's employee Cezar have been charged with corruption and, if convicted, this could lead to up to 12 years in prison. These cases remain ongoing.

To the federal police's charges, Marisa defended herself by saying she thought the money transferred to her bank account was related to Zerza's consulting work, an explanation that hasn't convinced Machado.

"He [Zerza] is the one that has to inspect and fine in case of any irregularities. But he goes and advises the company and charges for it. It is something totally incompatible [to his role]. He violates the duties of loyalty to the administration. One of the duties that public servants have is loyalty to the public administration," Machado said.

Zerza was fired by a state ministerial decree in March 2021. Source: Brazil's Official Gazette

Zerza was fired by a state ministerial decree in March 2021. Source: Brazil's Official Gazette

The civil actions against Indusparquet and the other timber companies, meanwhile, centre on the 2013 Brazilian Anti-Bribery Law making legal entities responsible for corruption regardless of whether their managers or directors knew what was going on.89

This law, nicknamed the Clean Company Act, stems from two international treaties – the Mérida Convention on tackling corruption and the Palermo Convention on transnational organised crime – and permits lawsuits if prosecutors have evidence that the company involved benefitted from corruption or an act that impeded inspection.

The case of Zerza meets these conditions, argues Machado, who explained the legal framework with the example of bribing a bureaucrat.

"Legally, corruption exists if I offer a bribe," he said. "I don't even need to pay – just the fact that I offer it is already a crime of passive corruption of the public official".90

"The public official, in turn, he does not need to receive [the money]. If he requests, he has already practiced the crime of active corruption".

Cezar continues to work at Indusparquet's headquarters in Tietê, São Paulo

Contacted for comment on the case, Indusparquet denied wrongdoing and stated that there was no link between Operation Patio and the federal prosecutor's lawsuit. It pointed out that the lawsuit does not show any environmental damage caused by Indusparquet and involved "mere questions on administrative information provided to Ibama." It maintains that it had no illegal relationship with Ibama employees.

In response to a request for comment, Uliana stated that it was available to clarify the facts once the case had been processed, but until it had, reporting on it could cause irreparable damage to the company.

Ulimax told Earthsight and Mongabay that it had not been proven that Zerza had acted on behalf of its firm or that it had contracted Zerza's services to commit unlawful acts. It does not deny it used Zerza's services however, stating that the hiring of the Ibama employee took place only "to assist the company in adjusting the stock kept in the Ibama system" and that such adjustments had not been possible to make due to inconsistencies in the system itself. It disputed the extent of penalties called for by the prosecutor, stating that if the penalties involved were properly calculated according to relevant legislation, "the amount of the fine, if due, falls considerably."

Baurupisos told Earthsight and Mongabay that given the evidence in records made accessible to the "civil public" and police investigation, there was no information in our allegations that was new to the company or its employees. However, it also stated that the evidence in the case was under judicial secrecy and that in view of this, it reserved the right to use legal measures against anyone publishing information from it that was damaging to the company.

The prosecutor confirmed that files in the civil case, which forms the basis for this report and which contain evidence of the charges against Indusparquet and its co-defendants, including Baurupisos, were freely accessible and are still free for Earthsight and Mongabay to use as they were obtained before they were placed under secrecy. The set of new cases filed by prosecutors against individual companies including Baurupisos, were placed under secrecy subsequently.

We did not receive a response from Demarchi, Faurtil or Thais Cristina Teixeira.

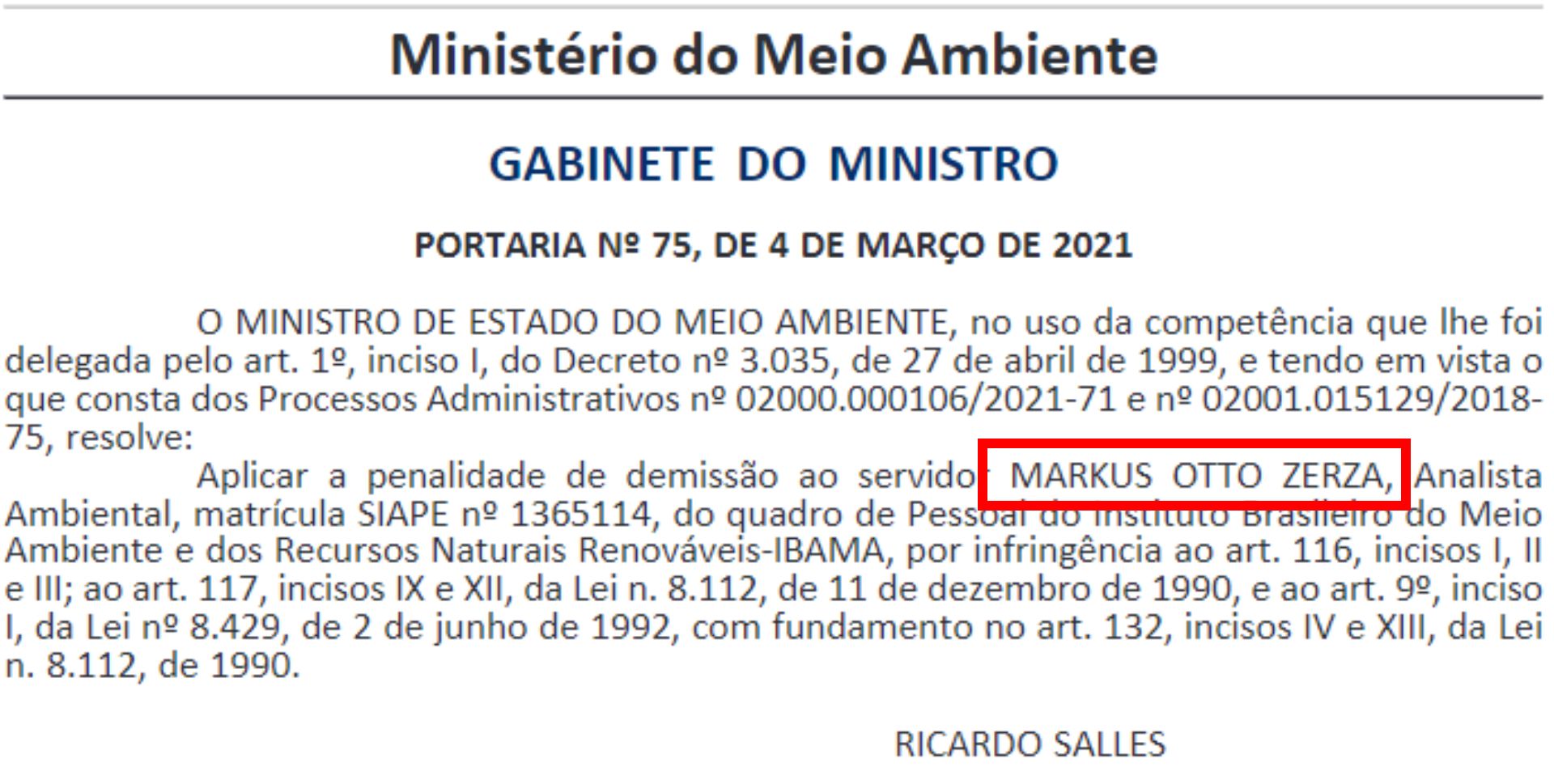

Despite admitting receiving bribes from Cezar to game the DOF system through his wife's bank account, Zerza remained a salaried Ibama employee for almost another three years, until 4 March 2021, when he was fired by a state ministerial decree.91

Describing Ibama as very cooperative with the investigation, prosecutor Machado nonetheless alleges that the agency had sat on evidence of crime within its ranks for years. He is now determined to finish the job. Not far from Machado's office, meanwhile, Cezar continues to work at Indusparquet's headquarters in Tietê, São Paulo.

***

The evidence furnished in the São Paulo civil case offers an insight into how an Indusparquet employee allegedly worked with a government official to game Brazil's national timber accounting system, at regular intervals, over years. The evidence in the case stops in 2017. However timber laundering via government databases remains common in Brazil today. Ibama continues to issue fines to companies for manufactured timber stocks and for discrepancies between the actual and declared volumes and species of timber in firms' possession every month. The next chapters reveal how Indusparquet's suppliers in other parts of Brazil have also been similarly fined for dealing in wood of dubious origin.

From Paraná in the South, and São Paulo in South-Eastern Brazil, the story now shifts to the heart of the Amazon rainforest in Pará state.

Friends in High Places

Busted

The Lucinilde Soares was crawling up the thick waters of the Mamuru river. Less than 50 kilometres on, the river would empty itself into the mighty Amazon. It was mid-November in the Parintins municipality of Amazonas state, the hottest month of the year. The ferry was sluggish under the weight of a heavy cargo – thousands of freshly cut ipê and massaranduba trees.

Then the usual sounds of the forest, interrupted by the occasional rumble of logging or other machinery, were broken by a more unusual sound – the drone of a rapidly approaching aircraft. It was a helicopter from the special aviation support branch of Brazil's Federal Police (PF). It had been deployed as part of Verde Brasil 2 (Green Brazil 2), a new inter-agency effort to crack down on illegal logging that Bolsonaro was forced to launch in response to the unprecedented international attention to soaring levels of deforestation in Brazil triggered by the forest fires of August 2019.

Within just a few hours, the ferry was swarming with PF agents, its documents checked and the discovery made that its precious cargo was wholly illegal. Police seized 3,418 cubic metres of wood lacking the correct information on the accompanying permits of timber origin (or DOFs) that day. They discovered high value tropical logs (which are also often more endangered) being declared as timber of species with much lower market values, a common ruse used by loggers the world over. The timber was reportedly on its way to Belém, a port on the Amazon river across the state border in Pará, from where it was due to be exported.

"We turned the satellite over there, started to look at that area and took them [the vessels and timber yards] down one after the other, in sequence."

The former police chief of Amazonas state who had masterminded the operation, Alexandre Saraiva, recalled how it began in a recent interview with Earthsight and Mongabay.

"In the week of November 15th, around the 12th [2020], agents came to me and said: 'The satellite is showing a great movement of ferries there in the south of the state, in the rivers. You can't be absolutely sure that it's wood, but everything suggests that it is.'"

The Federal Police seized wood on the border between the states of Amazonas and Pará in March 2021 as part of Operation Hadroanthus. Photo: Federal Police in Amazonas state via Smoke Signal

The Federal Police seized wood on the border between the states of Amazonas and Pará in March 2021 as part of Operation Hadroanthus. Photo: Federal Police in Amazonas state via Smoke Signal

"We arrested the commander because what was in the Guia Florestal [the term for timber transport permits in Pará], was not what was being transported on the ferry. We turned the satellite over there, started to look at that area and took them [the vessels and timber yards] down one after the other, in sequence."

The seizure of wood from the L. Soares triggered a series of other busts across Amazonas and Pará and marked the start of Operation Handroanthus, named after one of the most sought-after timbers in Brazil, the wood of the ipê tree.

Operation Handroanthus had officially become the largest timber seizure in the history of the Brazilian Amazon.

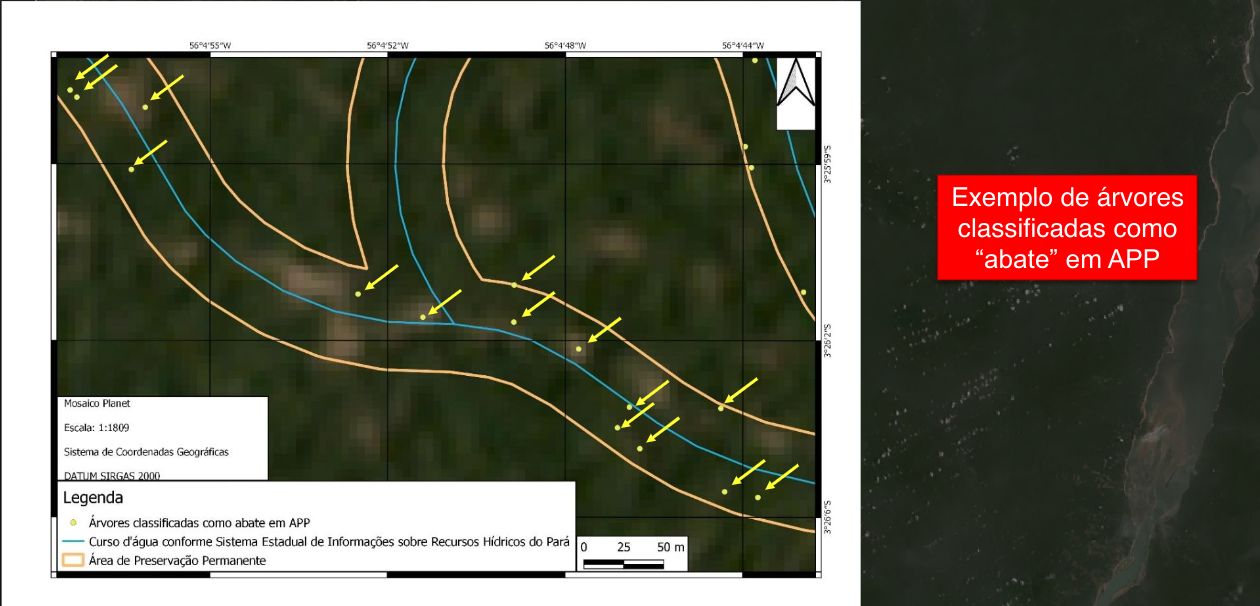

By the end of December 2020, the media was already reporting that a whopping 131,000 cubic metres of timber had been seized by police during the operation. And by April 2021, that number had leapt to 226,760 cubic metres of wood. Operation Handroanthus had officially become the largest timber seizure in the history of the Brazilian Amazon. The total value of the apprehended timber across all log yards and other areas – primarily located in the Amazonas and Pará states – was estimated by officials at more than 25 million US dollars. By Earthsight's reckoning, its retail value when sold as finished flooring overseas would have been an order of magnitude higher, at $448 million – nearly half a billion US dollars.92

A man of action

Ricardo Salles was on the move. His phone had been ringing off the hook for months and his diary was full of meetings with agitated members of Brazil's timber lobby. Operation Handroanthus had shaken timber suppliers up and down the Amazon to the core. Loggers had orders to fulfil. The only problem was, much of their timber had now been seized, put under guard by Brazil's Army (which played a collaborative role in Operation Handroanthus) while its fate was decided by the courts.

But Salles was not a man to wait for justice to be meted out by the courts. In fact, since his appointment as Brazil's Environment Minister in January 2019, he had been certain to miss no opportunity to use his position to grease the wheels for Brazil's timber industry and to help those involved avoid finding themselves on the wrong side of the law.

He had already had two meetings with a group of particularly concerned individuals, a young man named Rafael Dacroce among them. Dacroce, who was the elected councillor for a small town in Santa Catarina state in Southern Brazil, and a group of other politicians and loggers with investments in Pará had been eager to meet with Salles to discuss the seizures.

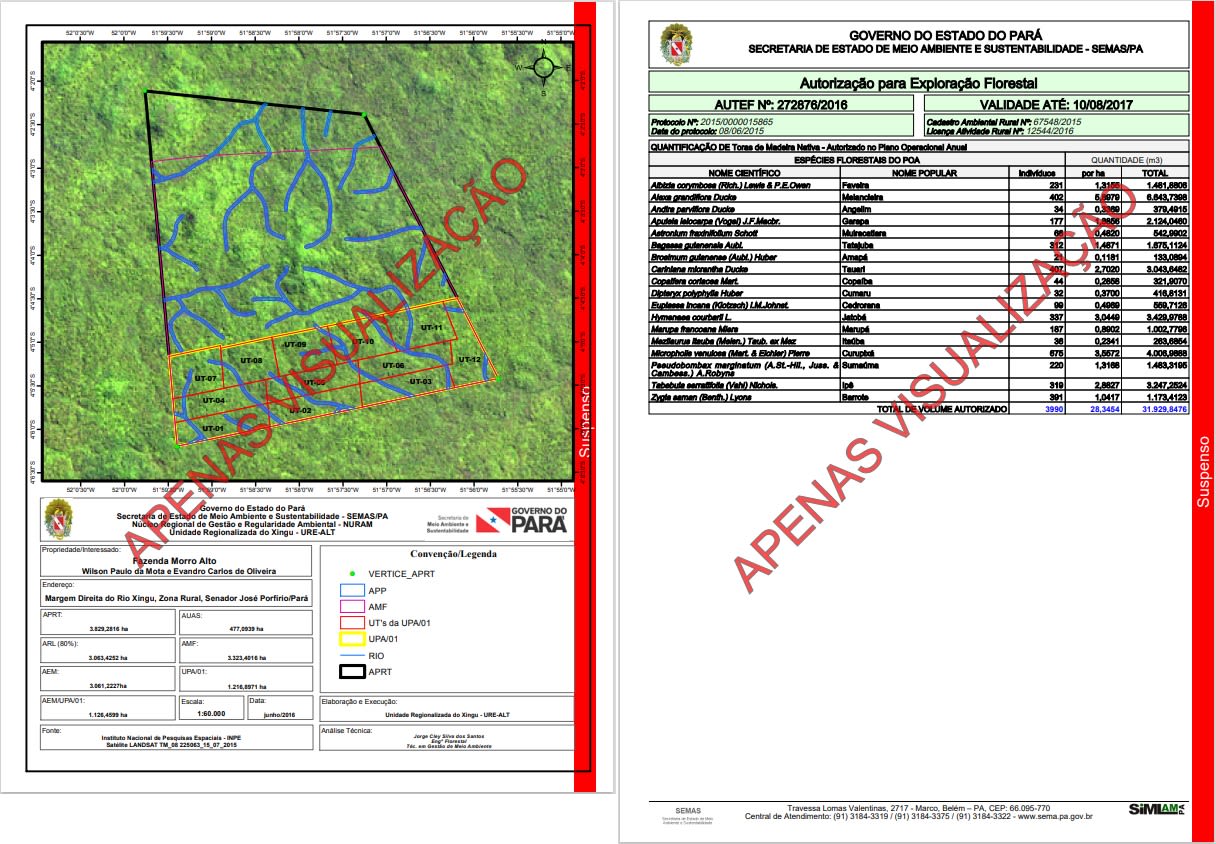

Rafael Dacroce is the grandson of Walter Dacroce, the owner of a farm named Francine II in Pará state. Francine had been among the targets of the Police's timber seizures during Handroanthus. Dubbed "professional land squatter" by media outlet Istoe, the Dacroce family’s partriarch [Walter Dacroce] was part of a wave of settlers to occupy land in Pará during the last 15 years.

It was at this meeting in mid-March 2021 that Salles reportedly made plans to visit Pará, to assess the situation with the logs seized during Handroanthus.

Rafael Dacroce posted a picture with Salles just after the meeting.

Dacroce shared this photo of himself and Salles on Facebook in 2021. The caption reads: "You know that picture you take full of pride and hope? Or the one you're going to print and put on your office wall? Well that's it! I believe in Brazil Minister of the Environment, Mr. Ricardo Salles!!". Source: Rafael Dacroce / Facebook

Dacroce shared this photo of himself and Salles on Facebook in 2021. The caption reads: "You know that picture you take full of pride and hope? Or the one you're going to print and put on your office wall? Well that's it! I believe in Brazil Minister of the Environment, Mr. Ricardo Salles!!". Source: Rafael Dacroce / Facebook

Questioned about the meeting later, Rafael Dacroce told reporters that Salles had promised to look into his case and to invite the head of Ibama and other politicians to do so too. "He wanted to understand, but at no time did he make a pre-judgment, look, oh, you're right, so we'll release the wood tomorrow."

But as it turns out, that was exactly what Salles tried to do.

The first stop on Salles' journey was a small village in the Santarém municipality in Pará state. Meeting some members of the timber sector there, he posted a Tweet on March 31 announcing that he had personally checked the origin of some wood there, and had verified its legality.

"There are serious people doing the job right. It is not right to demonize the entire timber sector. It is necessary to identify the criminals and punish them harshly, but without generalising," he declared on another social media post the same day.

The first stop on Salles' journey was a small village in the Santarém municipality in Pará state

A week later Salles returned to Pará with an entourage of politicians. The group included Zequinha Marinho, a Senator representing Pará state. Also along for the ride was the president of the House of Representatives' Environment Commission and part of the Brazilian delegation to COP26 in Glasgow in 2021.

Marinho and several other politicians had been pleading with Salles to do something about Handroanthus for weeks. In fact, Marinho's own press office admitted that he had sought out Salles after being requested to help by influential Brazilian timber lobby groups the Association of Wood Exporting Industries of the State of Pará (Aimex) and the Association of the Forest Productive Chain of the Amazon (Unifloresta).

The party finally made its way to the log yard, or 'patio' by the River Aruã where timber from the Francine farm was deposited before being loaded onto rafts and sent to be processed at various local sawmills. This had been one of the sites of the police raids. In fact, more timber was seized from the yards in this area than from any other – 18 per cent of the total.93

Posing in front of a sign portraying the name of the farm the log yard belonged to, Salles appeared to vouch for the legality of the seized wood: "You can see the patio [is organised] by property. Each property is tagged to identify the plot, the section within each plot, and the tree within each section. The tree has a number, which in turn has an exact location, a geolocation of the trees."

Alexandre Saraiva, the police chief who orchestrated the seizures, described the scene to local media soon after Salles' visit. "Salles arrived in a helicopter in one of Dacroce's farms used for the illegal extraction of at least 43,000 logs that were harvested illegally."

Rafael Dacroce took to Instagram again the very next day, unable to contain his excitement at the official visit. "Yesterday we had the pleasure of receiving in Santarém the Minister of the Environment, Mr. Minister Ricardo Salles, together with other authorities to supervise the legality of the extraction of wood in the State of Pará, coming from Sustainable Management Projects! This is the Brazil we want," he said.

Salles' interference in the Handroanthus operation would come back to haunt him

As it turned out, Salles' interference in the Handroanthus operation would come back to haunt him very soon.

Unable to stomach Salles' meddling, Saraiva wrote a letter to the Supreme Court a week after the Minister's visit to the Francine timber yard. In his letter dated April 1494, he outlined the evidence Operation Handroanthus had unearthed, and accused Salles of defending loggers and working to discredit police investigations. He said Salles acted "like a true advocate for the logging cause."

Excerpt from Saraiva's letter to the Supreme Court detailing the timber sector's collaboration with Salles in an attempt to impede the investigation. Source: Alexandre Saraiva

Excerpt from Saraiva's letter to the Supreme Court detailing the timber sector's collaboration with Salles in an attempt to impede the investigation. Source: Alexandre Saraiva

Saraiva was removed from his position as Head of Police for Amazonas state and demoted the very next day.

In bad company

The police superintendent's allegations were soon confirmed. Later that same month, in an interview to one of Brazil's largest news radio stations, Salles admitted that he had been pressured to act to release the wood seized in Handroanthus at the request of several politicians, including Marinho.

In May 2021, courts in Pará and Amazonas ruled that the timber seized in Operation Handroanthus should be released. The Amazonas judge's order was proudly shared by Salles on his Twitter account. The order by the Pará judge came the very same week that Salles visited Pará yet again, this time to supervise Ibama and police operations there.

Sempre fomos e continuamos sendo defensores da celeridade, devido processo legal e ampla defesa. Se estiverem errados que sejam punidos. Vejam, era mentira que ninguém tinha aparecido como dono da madeira e que não havia procurado a Justiça. Essa sentença de hoje desmente isso. pic.twitter.com/9IBQeMwBiB

— Ricardo Salles 2250 (@rsallesmma) May 5, 2021

Even that was not the end of the matter – in June, following a police request, Supreme Court Judge Carmen Lucia ordered the suspension of the decisions of the Amazonas and Pará judges to release the timber. She said that the police request had presented "very serious facts" and that the decision to release the "proceeds of the investigated crimes" was "premature" and could harm the investigation.

Later that month the National Council of Justice (CNJ), a watchdog which monitors judicial independence and conducts disciplinary hearings when wrongdoing is detected, began an investigation into Judge Antonio Campelo's conduct. Campelo was the Pará judge who had ordered the timber be released. On 12 December 2021, the CNJ decided he should be removed from his position as a federal judge in Pará.

Their probe found that Campelo's decision to summarily order the release of the wood had occurred while the judge was on vacation, that his hasty intervention had violated the judiciary's code of conduct, and that he had failed to act impartially and accurately.

Brazil's Supreme Court authorised an investigation into whether Salles obstructed a police probe into illegal logging in the Amazon, especially Pará

As for Salles himself, Saraiva's letter to the Supreme Court may have cost the police chief his job, but its detailed account had rung alarm bells among top prosecutors in Brazil's capital, spurring them into action. In early June 2021, the Supreme Court authorised an official investigation into whether Salles had obstructed a police probe into illegal logging in the Amazon, especially Pará.

Two weeks before this, another unrelated criminal investigation was launched against Salles for his alleged participation in illegal logging schemes "of transnational character."

Facing mounting pressure as a result of the two Supreme Court investigations, Ricardo Salles resigned from his post on June 23rd 2021. His days of helicopter rides following police raids in the Amazon had been brought to an abrupt halt.

There is no smoke without fire

A minister had resigned, a police chief been demoted, and some of the seized wood released under highly dubious circumstances. But Operation Handroanthus was not done making waves.

Despite the controversy surrounding the seized wood, in January 2022 President Bolsonaro's own lawyer Frederick Wassef stepped in to secure a court order to release part of it. Wassef wasn't representing Bolsonaro on this occasion, but a timber company named MDP Transportes, one of the firms whose timber had been seized in the operation.

President Bolsonaro's lawyer stepped in to secure a court order to release some of the seized wood

Federal Prosecutor Raquel Branquinho criticised the decision. She said their investigation had been hampered by the decision to release part of the timber apprehended in the operation. She added the release should only have been made once the wood had been properly identified, since loggers' attempts to legalise wood of dubious origin had been the very subject of the criminal investigation.

Earthsight decided to do a little more digging into the case, including exploring where the timber associated with the scandal might have ended up. We took a closer look at two farms in Pará whose wood was seized during Handroanthus, and in both cases our path led us back to none other than our old friend, Brazilian flooring giant and scandal-magnet Indusparquet.

Article on the court order by Brazilian news website Metrópoles. The headine reads "Wassef manages to release wood retained in Salles' administration in court". Source: Metrópoles

Article on the court order by Brazilian news website Metrópoles. The headine reads "Wassef manages to release wood retained in Salles' administration in court". Source: Metrópoles

MDP Transportes, the timber company Frederick Wassef was representing, operates a concession in Pará and had been among the firms that had its wood seized. In summer 2021, Federal Police in Amazonas had detected that, in the wake of the Handroanthus seizures, some of the seized logs had started disappearing or were sold within the yards of the companies targeted by the operation – even though they were supposed to be under guard.

Police documents obtained by media outlet CartaCapital showed that between June and August 2021, 31,500 cubic metres of wood were moved from the log yard of MDP Transportes in Pará. This was several months before the release order Wassef helped the company secure in January 2022, and in violation of the Supreme Court suspension in June 2021 that had reversed previous orders to release the logs.