Taiga King 2:

Back In Business

A Russian tycoon flooded Europe with dirty wood.

He got away with it.

So did his customers.

Here's how they did it.

Introduction

- In December 2020, Earthsight revealed how EU firms had been sourcing wood linked to a vast timber corruption case in Russia, involving stolen goods with a street value of almost a billion dollars.

- The wood, from the precious 'taiga' forests in far eastern Russia, had been 'certified' as legal by global wood green label PEFC. We alerted authorities tasked with implementing an EU law meant to ensure wood imports are legally sourced.

- Now, Earthsight reveals that the trade continues, with import officials apparently powerless to stop it.

- The case has important implications for the design of a new law under development in the EU which aims to address its role in driving deforestation overseas through consumption of commodities like palm oil, soy and beef.

- It demonstrates that such a law cannot rely on flawed green labelling schemes, and must also be designed with multiple checks and balances in order to ensure that it is meaningfully implemented and enforced. This includes reinserting a requirement for firms found in breach to be named and shamed.

Companies in the European Union and Britain are still buying lumber linked to one of Russia's largest logging scandals, which saw corruption threaten forests vital to avoiding climate breakdown.

An Earthsight investigation reveals the ongoing trade – and raises fresh concerns that laws meant to stem the tide of illegal timber into the continent are not implemented effectively.

The findings prompted representatives of two national competent authorities to back calls for the European Commission to issue formal guidance on importing timber from Russia. The EU's executive arm adopted a similar document for Ukraine last year.

Russia's taiga, or boreal, forests hold vast amounts of carbon in frozen soils. Together with tropical rainforests like the Brazilian Amazon, they act as the planet's lungs, sucking carbon dioxide from the air and producing oxygen.

Apocalyptic wildfires have destroyed large swathes of these forests in recent years, releasing record levels of greenhouse gases. Human-driven climate change is fanning Siberia's blazes, with logging making the forests more vulnerable to them.

Aerial view of forest fire in Russia's Krasnoyarsk region, July 2020 © Julia Petrenko / Greenpeace

Aerial view of forest fire in Russia's Krasnoyarsk region, July 2020 © Julia Petrenko / Greenpeace

Amid this backdrop, a December 2020 Earthsight report, Taiga King, exposed how Russian tycoon Alexander Pudovkin flooded Europe with dirty wood. This happened in spite of the EU timber regulation (EUTR) and an equivalent UK law forcing companies to check their supplies to reduce the risk of trading illegal timber to a "negligible" level.

The report generated headlines across Europe and Russia, with major media outlets like The Guardian, Der Spiegel and Tagesschau, the national German TV station's website, highlighting their homegrown firms' connections to corruption and environmental abuses.

Several of the EU companies caught importing Pudovkin's timber pledged to investigate, as did competent authorities on the continent after Earthsight filed complaints.

Now, interviews with import officials show Pudovkin's customers walked away largely unpunished. And customs records obtained by Earthsight list thousands more tonnes of the timber as entering Europe last year.

The manufacturer named in the records is Logistic Les, part of the BM Group conglomerate formerly headed by Pudovkin. His corporate empire has largely crumbled, though his ex-wife, Natalia – who now heads BM Group – and their two sons remain in the fold. The conglomerate and its current chief did not respond to emails seeking comment.

Earthsight report Taiga King was published in late 2020 © Earthsight

Earthsight report Taiga King was published in late 2020 © Earthsight

Earthsight's latest findings raise questions for EU lawmakers, who are set to vote on legislation that would force firms to ensure they have no deforestation in their supply chains. Britain has already passed such a bill.

They demonstrate how no law, however ambitious, can stop the destruction of the world’s forests without vigorous enforcement.

They also reveal further missteps and failures by the Programme for the Endorsement of Forest Certification (PEFC), an international green organisation whose seal of approval allowed the Pudovkins to reach lucrative markets outside Russia.

PEFC cut ties with Logistic Les and sister firm Asia Les after the scandal broke but maintains their parent outfit did not breach its standards. BM Group was allowed instead to hand back its coveted PEFC certificate without admitting wrongdoing, following requests for comment for this article.

Environmental campaigners have long called for PEFC to close a loophole in its rules allowing companies affiliated with firms responsible for harmful practices to remain certified.

Crime And Punishment

Alexander Kalievich Pudovkin was once a titan of Russian logging, controlling a forest empire from the country's far eastern Khabarovsk region.

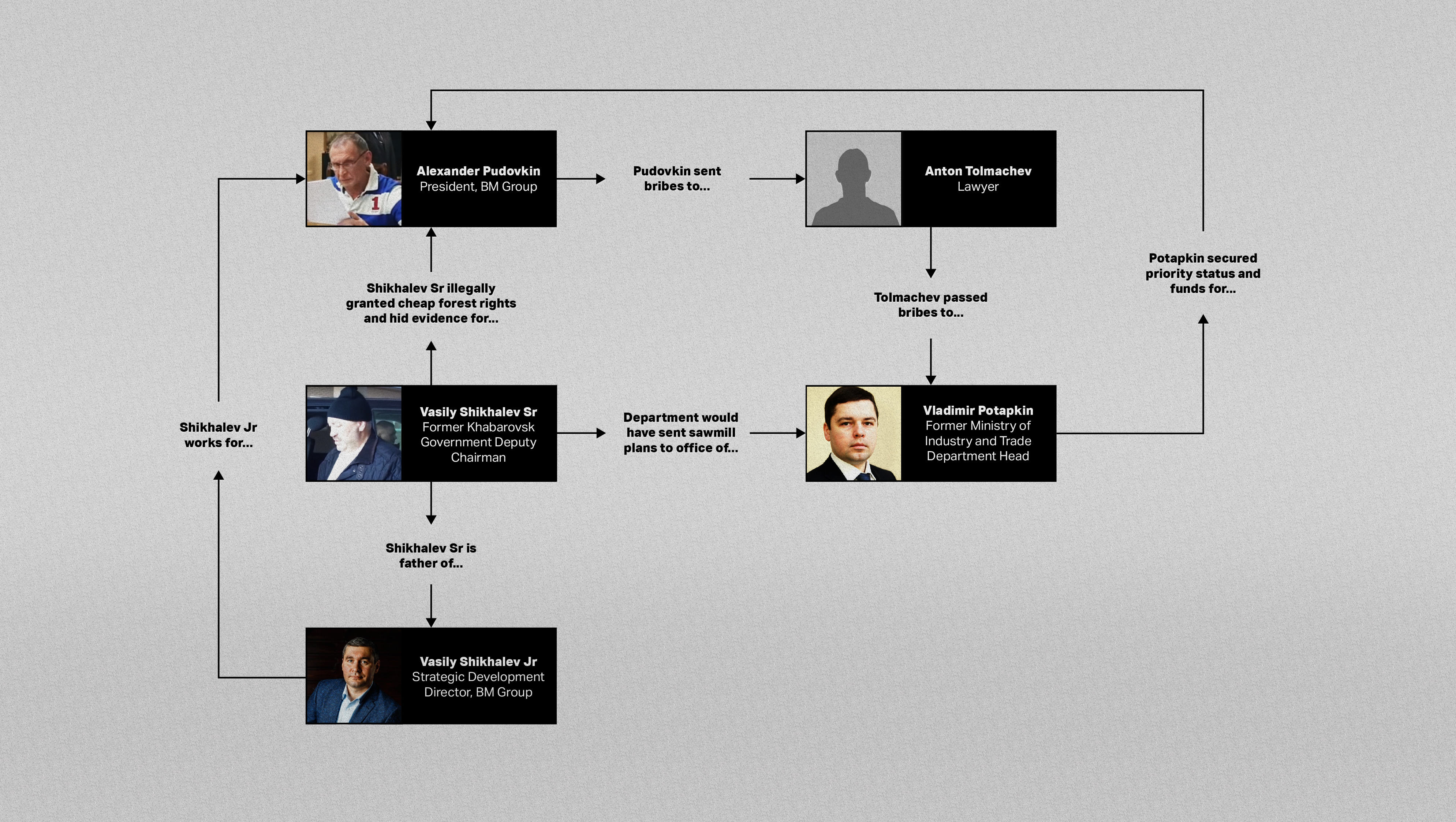

But in March 2019, Russia's FSB domestic security agency raided the BM Group headquarters. Pudovkin was arrested and placed under investigation alongside government officials Vasily Shikhalev and Vladimir Potapkin.

Earthsight's Taiga King report documented the tycoon's rise and spectacular fall.

It centred on the BM Group firm Asia Les, now in bankruptcy proceedings. Russian prosecutors have claimed the company's unfinished sawmill venture caused as much as $140 million in damages to the state budget, primarily through industrial-scale illegal logging.

Pudovkin had then confessed to bribing Potapkin, a high-ranking Moscow official who added Asia Les to a federal list of priority investment projects and showered it with subsidies.

Alexander Pudovkin at the 2018 Eastern Economic Forum. Photo: Dmitry Yefremov / TASS

Alexander Pudovkin at the 2018 Eastern Economic Forum. Photo: Dmitry Yefremov / TASS

Handed forests and funds through illicit deals to make planks and wood pellets in a purpose-built factory employing hundreds, Asia Les instead used them to send unprocessed logs in bulk to China.

Prime minister Dmitry Medvedev opened the site's pellet plant via videolink in late 2017, though delays mounted and the hoped-for sawmill central to the deal never materialised.

A federal audit exposed the fraud in December 2018. It revealed widespread rule-breaking, including that the company was passing off timber made elsewhere as its own.

Taiga King had also uncovered likely evidence of wood laundering. When Russian authorities launched a crackdown on Asia Les, sister firm Logistic Les, also briefly on the priority list, started exporting timber of the same type and quantities as its sibling had done.

Local officials investigated too, but Pudovkin's friend Shikhalev, then in charge of Khabarovsk's forestry sector, obstructed them and hid evidence. His actions earned him a suspended prison sentence in March 2020.

BM Group dismissed Earthsight's findings as "biased" and "incorrect", adding that the legality of the timber concerned had yet to be settled in court. Pudovkin did not comment.

This satellite image of the Asia Les site was taken in October 2018.

It shows some new features.

But where is the sawmill?

Here is the log sorting line.

Here is the railway depot for loading goods for transport.

Here is the pellet plant.

So where do you make timber?

What about these buildings?

Another BM Group firm owned them.

Asia Les was sawing timber here.

Source: Slide from BM Group PowerPoint presentation (2013)

Source: Slide from BM Group PowerPoint presentation (2013)

A week after Taiga King came out, in late December 2020, Pudovkin escaped punishment for his central part in the scandal when a Russian court dismissed the bribery case against him, citing his "active repentance" for his actions.

Prosecutors said he had admitted guilt and implicated both the bribe-taker – Potapkin, who was sentenced in October to more than a decade in a penal colony for his involvement – and the middleman in the illegal payments, Anton Tolmachev, their mutual friend who remains at large.

Initially charged with bribery, fraud and complicity in abuse of office, Pudovkin reportedly agreed to name names in exchange for having the latter two charges dropped. With the remaining one for bribery dismissed, he quietly stepped down as boss of BM Group.

A Russian corporate registry shows that his ex-wife Natalia, the conglomerate's managing director and public face during the scandal, took the helm in March 2021.

Alexander and Natalia's two sons, Alexey and Ivan, meanwhile, remain joint owners of Logistic Les, which is also in bankruptcy proceedings.

Asia Les was eventually fined for the sawmill swindle in June of last year. Local prosecutors confirmed to the news agency AmurMedia that the company broke the rules on state subsidies to businesses by failing to fulfil its state support deal.

Connections and conflicts of interest in the Asia Les scandal, December 2020 (Pudovkin has since left BM Group). Photos: FSB Directorate for Khabarovsk Territory; minpromtorg.gov.ru; LinkedIn / Василий Шихалев. Illustration: Matt Hall for Earthsight

Connections and conflicts of interest in the Asia Les scandal, December 2020 (Pudovkin has since left BM Group). Photos: FSB Directorate for Khabarovsk Territory; minpromtorg.gov.ru; LinkedIn / Василий Шихалев. Illustration: Matt Hall for Earthsight

Back In Business

For image-conscious corporations in Europe, Taiga King should have been further proof of a controversy to avoid. And yet, the lure of cheap wood seems to have proved too strong for some.

Several companies named as BM Group's top European customers pledged to investigate or otherwise tried to distance themselves from Pudovkin. As explained below, only one announced the results of its probe: Jacob Jürgensen, Europe's largest importer of Siberian larch.

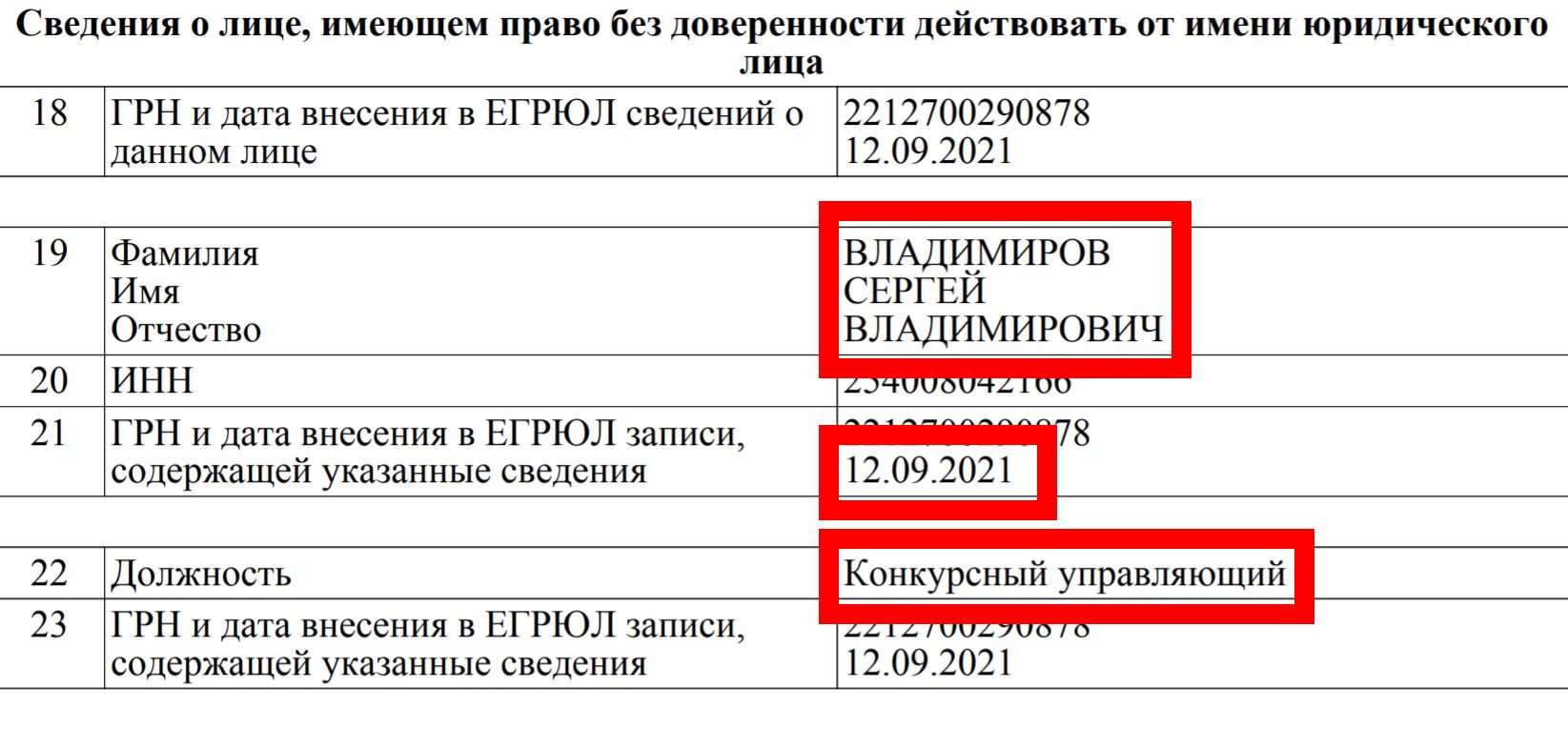

Customs records obtained by Earthsight from an import-export database not only show that European imports of timber harvested by BM Group companies paused after the exposé, but that they resumed last summer, shortly before a court-appointed bankruptcy trustee took charge of Logistic Les, the company jointly owned by Pudovkin's sons.

A bankruptcy trustee ("Конкурсный управляющий") took charge of BM Group subsidiary Logistic Les in September last year, company filings show. Source: Russian State Register of Legal Entities

A bankruptcy trustee ("Конкурсный управляющий") took charge of BM Group subsidiary Logistic Les in September last year, company filings show. Source: Russian State Register of Legal Entities

The records tallied 167 shipments of timber manufactured by Logistic Les out of Russia from June to August last year.

About 13,600 tonnes of timber worth nearly $2.6 million, mostly larch boards and planks, left the country over the period, according to the records, which contain no mention of the wood being certified by PEFC or other sustainability bodies.

Goods continued to flow after the fine imposed on Asia Les in June, the customs records show.

Two-thirds of the timber was traded to China, with a small proportion going to Japan, the records show. A large amount also went to buyers in the European Union and Britain, mostly to Germany's Jacob Jürgensen, which accounts for more than half the volume of timber exported to the continent, according to the records. They also report smaller volumes going to three other German firms, as well as one company registered in the UK, France, Belgium, Denmark and Estonia, respectively.

The records name third-party trader SDS Logistic as supplying all shipments bar three bound for Japan. The Khabarovsk outfit, whose previous founder listed on company filings was a former general manager of Logistic Les, has close links to BM Group. Both share an office building and a consultant handling their PEFC papers.

EU And UK Buyers

Nine European corporations received a combined 3,380 tonnes of Logistic Les timber with a total invoice value of nearly $1.3 million last year, Earthsight can reveal.

Only five of them replied to emails seeking comment. Jacob Jürgensen and French trader Henry Timber, two companies accounting for the bulk of shipments to Europe, insist their activities comply with the law; the three remaining firms, which Earthsight has chosen not to name, dispute the data.

The declared importers include German firms Jacob Jürgensen, named in shipping records accompanying about 1,800 tonnes of the timber; Ost-West Holzhandels (OWH), in Essen; and the Kempten-based Weissenbach International, whose managing director, Toni Weissenbach, told Earthsight in 2020 had been "one of the few importers in Europe" to refuse goods from Pudovkin and his businesses. Neither OWH or Weissenbach International answered requests for comment.

However, after nine days of silence and multiple messages, Jacob Jürgensen's managing director Rolf von Loßberg did.

He said he had been given insufficient time and context to comment, given the "little information" Earthsight provided in the form of a four-page document outlining the facts.

Regardless, von Loßberg offered general statements in an emailed response largely recycled from his reply for Taiga King. In it, he reiterated that his company saw no reason to doubt it was in compliance with EUTR, the EU law on timber imports, which he said was strictly monitored in Germany.

Jacob Jürgensen had also made similar comments after domestic media interest led it to hire two employees in Siberia to investigate the December 2020 report's findings.

In response to Earthsight's Taiga King report, Jacob Jürgensen declared in February 2021: "the allegations made could not be supported or confirmed." The company did not specify which facts this referred to, nor provide documents refuting them. Source: Jacob Jürgensen

In response to Earthsight's Taiga King report, Jacob Jürgensen declared in February 2021: "the allegations made could not be supported or confirmed." The company did not specify which facts this referred to, nor provide documents refuting them. Source: Jacob Jürgensen

It declared in an online statement dated 18 February 2021: "the allegations made could not be supported or confirmed". The statement, which did not name Pudovkin or his businesses, included no supporting documents and did specify which facts this referred to.

Instead, Jacob Jürgensen cited an internal report and "confidential" files from its long-standing Russian supplier as evidence that everything complied with the law.

Alluding to the dismissed bribery case against Pudovkin – kickbacks he publicly admitted – and the fact that BM Group held a coveted PEFC certificate – even though Asia Les and Logistic Les had been stripped of theirs – the German trader announced it had resumed imports.

The federal agency for agriculture and food (BLE), which enforces EUTR in Germany, however, had reached the opposite conclusion. The imported timber mentioned in the report did not meet the law’s required "negligible" risk of being illegal, a representative told Earthsight (see 'Regulatory Woes').

Patrick Faure, president of Henry Timber in southeastern France, meanwhile, appeared to confirm sourcing the timber through a supplier called Finepine but denied any wrongdoing. Independent inspections vouched that his company’s supply chain checks met the requirements of the law, he added.

Faure told Earthsight his firm only buys Russian timber from suppliers certified by PEFC or its rival sustainability body, the Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), given the risks of doing business there. Both suppliers – SDS Logistic and Finepine – hold PEFC certificates, but Logistic Les, the manufacturer named in the customs records, did not and does not.

Emails seeking comment from the two remaining European importers mentioned in the records – Wellmax Baltic, an Estonian dealer of Siberian larch, and Goka Ltd, which is registered to address in London but operated from Spain by two Russian nationals – went unanswered.

Problems For PEFC

The last year witnessed Logistic Les offloading large quantities of suspect timber to Europe with its dying breath, and further confirmation of fraud and corruption through the fine against Asia Les and the conviction of Moscow official Vladimir Potapkin, prompting more questions for PEFC.

Its logo alone does not prove wood complies with EUTR or equivalent legislation in Britain. And its scheme is entirely voluntary.

Yet the Geneva-based non-profit has seen its green label adorn household products, books, furniture, food packaging and other goods around the world.

PEFC logo. Source: PEFC

PEFC logo. Source: PEFC

Exporters worldwide are increasingly turning to certification bodies like PEFC and FSC to reassure consumers and governments in the lucrative US and European markets that their wood is sustainable and legally harvested. As are Europe's timber traders, eyeing an abundant supply of cheap wood from "high-risk" areas like Russia.

But PEFC gave BM Group's customers a false sense of confidence. Its audits failed to mention flagrant fraud documented by Russian authorities and covered in the media. And yet, European importers relied heavily on PEFC's judgement to justify their business dealings with the conglomerate, even though its sister outfits, Asia Les and Logistic Les, had been stripped of their sustainability status after the scandal broke.

PEFC said the certificate for the Pudovkins' timber conglomerate had been "voluntarily" terminated on 12 January – i.e. after Earthsight contacted them both for comment. Source: PEFC

PEFC said the certificate for the Pudovkins' timber conglomerate had been "voluntarily" terminated on 12 January – i.e. after Earthsight contacted them both for comment. Source: PEFC

Michael Berger, PEFC's acting secretary general, told Earthsight the certificate for BM Group had been terminated, meaning the conglomerate had "voluntarily" withdrawn it, as of 12 January – i.e. after requests for comment for this article.

In a statement dated 14 January, Berger said the sustainability body saw no evidence that BM Group broke its rules. (He also asked Earthsight to send "substantiated" evidence otherwise to the audit firm and PEFC-certified companies embroiled in the case, which did not address how the green label's rules had in effect condoned corruption and fraud.)

Inspecting The Inspectors

PEFC subcontracts its audits of logging operations to for-profit firms. Tasked with supervising BM Group and its businesses was SGS Vostok, the Russian branch of the world’s leading, and much maligned, inspection company, SGS.

After the scandal broke in 2019, PEFC's local arm asked the Moscow-based firm Industrial Safety to investigate SGS Vostok. As a result, Asia Les was stripped of its PEFC certificate. Logistic Les also lost its certificate on an unspecified date.

BM Group, the parent outfit over which PEFC's own records show Pudovkin exercised total control, however, retained the green organisation's seal of approval. And when Earthsight asked both PEFC and its Russian subsidiary to comment for Taiga King, Industrial Safety was dispatched to investigate again.

PEFC records say BM Group's leader "makes decisions on all issues on the basis of unity of command." Source: PEFC

PEFC records say BM Group's leader "makes decisions on all issues on the basis of unity of command." Source: PEFC

PEFC relied on SGS, whose Russian arm was under scrutiny for a second time, to clear itself – and by extension PEFC – of blame (see 'Whitewash?'), despite later suspending the same local branch from performing certification duties.

SGS Vostok had its licence to issue PEFC accreditation suspended in September last year after Industrial Safety's second probe found a number of issues, which the green label did not specify. Acting PEFC chief Michael Berger cited "non-conformities," without elaborating.

Berger told Earthsight the ban was lifted temporarily on Christmas Eve after the Russian inspectors "addressed" the concerns. This would remain until 28 February, by which time Industrial Safety will have sent a final report, he added.

Industrial Safety deputy director Matvey Belov declined to share the report, citing a confidentiality agreement and company rules. But he did tell Earthsight his company's next inspection of SGS Vostok was scheduled for the first half of this year, and that representatives for PEFC Russia would participate.

Whitewash?

SGS Vostok's brief ban sheds new light on its initial, curt reply to Taiga King. Responding to Earthsight in 2020, the company issued a brief statement that did not address the report's findings but said that its activities comply with Russian law and PEFC standards.

After the international news media picked up on the story, a spokeswoman for the SGS head office in Geneva told Der Spiegel the matter was being taken "very seriously" and that the company's chief compliance officer had dispatched a team to investigate.

Ben Gunneberg, then CEO of PEFC, also filed a complaint with SGS, whom he asked to "promptly contact" Earthsight.

Then, a long silence – no emails from SGS, no phone calls, no word.

SGS Vostok's October 2020 statement for Taiga King. Source: Earthsight

SGS Vostok's October 2020 statement for Taiga King. Source: Earthsight

In January 2021, the month after Taiga King came out and Pudovkin walked free, Earthsight investigators submitted complaints under EU and UK law to competent authorities in the countries named in customs records as destinations for the tycoon's timber.

The investigators again urged them to take action during a presentation to the European Commission expert group on protecting and restoring the world's forests in late February of that year, during which the lack of update from PEFC was mentioned.

Shortly afterwards, the sustainability body sprang into action. In a news release dated 3 March 2021, PEFC announced that SGS did not find any indication that the timber sold broke Russian law or its standards.

PEFC relied on SGS, whose Russian branch was embroiled in the scandal, to clear itself – and by extension PEFC – of blame. SGS's local arm was later suspended after a second investigation into how it handled Pudovkin's companies. Source: PEFC

PEFC relied on SGS, whose Russian branch was embroiled in the scandal, to clear itself – and by extension PEFC – of blame. SGS's local arm was later suspended after a second investigation into how it handled Pudovkin's companies. Source: PEFC

An obvious conflict of interest went unmentioned: SGS – then under investigation again in Russia – had inspected itself and risked losing business with PEFC if it concluded otherwise.

The SGS report has not been publicly released, and Christian Kobel, the firm's global business manager for forestry, refused to share it. Instead, he sent Earthsight a one-page statement on its findings.

The statement reads more like a defence of SGS's handling of BM Group and its businesses. (For a detailed analysis, see 'SGS's Statement, Unpacked'.) It made clear that SGS saw nothing wrong and would not take action.

Did regulators in Europe agree?

SGS's Statement, Unpacked

Based on the SGS statement, the inspection giant's report appears to have overlooked undisputed evidence of crimes connected to Pudovkin and BM Group.

Click here to read more

Regulatory Woes

So how did the European and British bodies enforcing the laws on timber imports respond to Earthsight's complaints?

With mixed enthusiasm, it emerged.

One of Russia's largest logging scandals – involving spies, lies, bribes and betrayal – had dumped massive quantities of suspect timber at their feet. And the companies who cashed in on the goods, much like Alexander Pudovkin himself, escaped mostly unscathed.

Seven competent authorities who received the dossiers, known as substantiated concerns, disclosed the results of their investigations. Their counterparts in Hungary also got in touch, which was encouraging, as Taiga King hadn't mentioned the country.

In Germany, BM Group's largest European market by far, BLE officials inspected three firms named in Earthsight's evidence, said a representative for the federal agency, who did not name the companies.

Two of them "had knowledge" of the Siberian scandal and accounted for it risk assessments forming part of their supply chain checks, he told Earthsight.

But after the documents were revised, both companies no longer thought the timber met the EUTR's required "negligible" risk of being illegal, the official said. "This assessment is unobjectionable," he added.

The third company was unaware of the matter, the official said. But since the imported wood had been certified by PEFC, the BLE slapped it with an enforcement order under German law that if broken, constitutes an administrative offence punishable by a fine.

The German official and Jan Ďoubal, his Czech counterpart, also voiced support for the European Commission to issue formal guidance for importing timber from Russia.

The EU's executive arm has already adopted a similar document for Ukraine, which formally recognises that the country's timber does not meet EUTR’s requirements just because it is certified by green organisations like PEFC or FSC. Entrenched corruption there also means official documents, including certificates of origin for wood and online timber tracking databases, alone do not reduce the risk of importing illegal goods, it states.

The German and Czech officials both echoed the same concerns, referring to Russia.

In what may prove to be a crucial turning point for efforts to protect Ukraine’s forests 🇺🇦🌳 from illegal loggers, the EU has officially declared that flawed green labelling scheme FSC’s systems are unable to ensure its wood is legal:https://t.co/bYZXsR9c2K

— Earthsight (@earthsight) June 23, 2021

Ďoubal, from the Czech competent authority, told Earthsight he and his colleagues faced secrecy from the leading green labels, whom he considered "reliable with reservations".

"PEFC/FSC do not inform us openly enough about misconduct in supply chains, about suspended/terminated certifications, and about the reasons the certification was terminated," he told Earthsight via email.

Ďoubal mentioned, as an example, that the monitoring body has no access to audit reports accompanying the wood labels' widely-used 'chain of custody' supply chain certificates, which account for a large share of their income. Environmental and civil society groups including Earthsight have long demanded these be made public.

"The EUTR legislation is very complicated to enforce because of no clear definition of 'illegality' and the existence of letterbox and offshore companies," he added.

Investigations by Earthsight have often uncovered shell firms and entities registered in secretive jurisdictions bearing 'chain of custody' certificates from PEFC or FSC. When audits reports accompanying these papers remain secret, it is difficult to verify whether their activities are legitimate.

Ďoubal also mentioned the difficulty of dealing with illegal timber that had often reached Europe long before the Russian authorities prosecuted the loggers responsible – a time delay that also hindered action on the Asia Les case.

Due diligence information on shipments to Latvia and Austria – concerning small volumes of timber imported years before the scandal emerged – was no longer available, said officials in the respective competent authorities. The Latvian firm responsible was reminded that sustainability certificates alone did not constitute proof that the timber complied with EUTR; in Austria, no action was taken.

And, in Lithuania, another minor market for BM Group, the monitoring body there told Earthsight that the importer responsible had already gone bust. No action was taken.

Onward to Denmark, whose competent authority called two recorded consignments of timber "test deliveries" from an importer with "satisfactory" checks in place. No action was taken.

Back in the Czech Republic, Ďoubal, whose team investigated Earthsight's complaint, said an inspection of the company whose name appears on customs records accompanying six import shipments of timber did not find proof that Asia Les or its BM Group affiliates were in its supply chain. His team did, however, recommend "some improvements" to the firm's due diligence checks.

In Belgium, a major European market for BM Group, a EUTR official declined to discuss operational matters but confirmed an ongoing probe prompted by Earthsight's research.

Notably silent were the respective regulators in the UK, who acknowledged the email containing our evidence; Estonia, who did so through an automated response; and France, Slovakia and Sweden, who all failed to reply.

Passing Laws That Work

This case demonstrates all too painfully that no law, however ambitious in scope, will be good enough to make an impact on skyrocketing deforestation levels if governments in the EU are not equally ambitious about overcoming the hurdles to effective enforcement.

This has important and urgent implications for EU lawmakers. The bloc has committed to expanding its existing law on timber to cover other commodities driving deforestation overseas, like palm oil, beef and soy, and to banning these commodities if linked to deforestation, whether legal or not.

The draft law, currently being considered by the European Council and MEPs, contains several new clauses intended to address the implementation problem. It will make it mandatory for customs agencies and other authorities to share information and require monitoring bodies to investigate concerns submitted by civil society groups. The draft includes traceability rules, requires penalties to be proportionate to the damage caused, and sets minimum requirements for numbers of compliance checks by authorities. It allows for the public to sue EU authorities if they fail to carry out their duties.

It remains uncertain, however, whether all this will be enough. More checks are only of use if they are able to detect wrongdoing, and this case gives little cause for hope in that regard. Most of the new details on penalties relate to what authorities in member states must be empowered to do, but don't actually force them to use those powers. And it is hard to see how compliance by authorities with the proportionality clause will itself be enforced by Brussels or the courts, since the value of damage caused is such a grey area.

Would EU imports of timber from the Russian businesses exposed in Taiga King still have occurred had the new regulation, with its improved penalty, traceability and compliance requirements, been in force at the time of the scandal? The sad truth is that they probably would have.

More will be needed if the new law is to work better. One crucial clause in an early draft of the new rules was dropped: a requirement for authorities to publish lists of non-compliant companies. This has the big advantage of being readily enforceable, and serves as a powerful deterrent in itself, regardless of how weak the penalties given were. This is especially true of the largest firms with the biggest brands to protect, and there are many more of these that the new law will cover that EUTR did not. The European Council and MEPs must demand this 'name and shame' clause be reinserted.

"This case makes shockingly clear that the EU's previous legislative efforts to cut its ties to predatory logging and deforestation overseas have failed. The EU's new, expanded law will also fail spectacularly unless lessons are learned."

As it stands, perhaps the biggest challenge in the next few months will be to keep the strongest elements of the draft as they are and to counter efforts from industry to water it down. One of the key ways in which they are seeking to do so is to call for certification schemes to be given a formal role in meeting the requirements of the planned proposal.

Earthsight reported in November how Europe's leading timber lobby has demanded the draft controls exempt products approved by green labels such as the one that rubberstamped the suspect timber in the Taiga King case. As this and many other scandals have demonstrated, such a move would be a disaster. The Council and MEPs must fight such efforts tooth and nail.

February 2022

Credits

Opening footage and images: FSB Directorate for Khabarovsk Territory / Люди ДВ / YouTube

Who's Who images: Evgeniy Egorov / Roscongress Foundation / forumvostok.ru; Телеканал Хабаровск / YouTube; Matt Hall for Earthsight; minpromtorg.gov.ru; FSB Directorate for Khabarovsk Territory

Satellite image: Maxar Technologies / Google Earth

European Union flags photo: Thijs ter Haar (licensed under CC BY 2.0)