Inside the environment ministry: Karen's Story

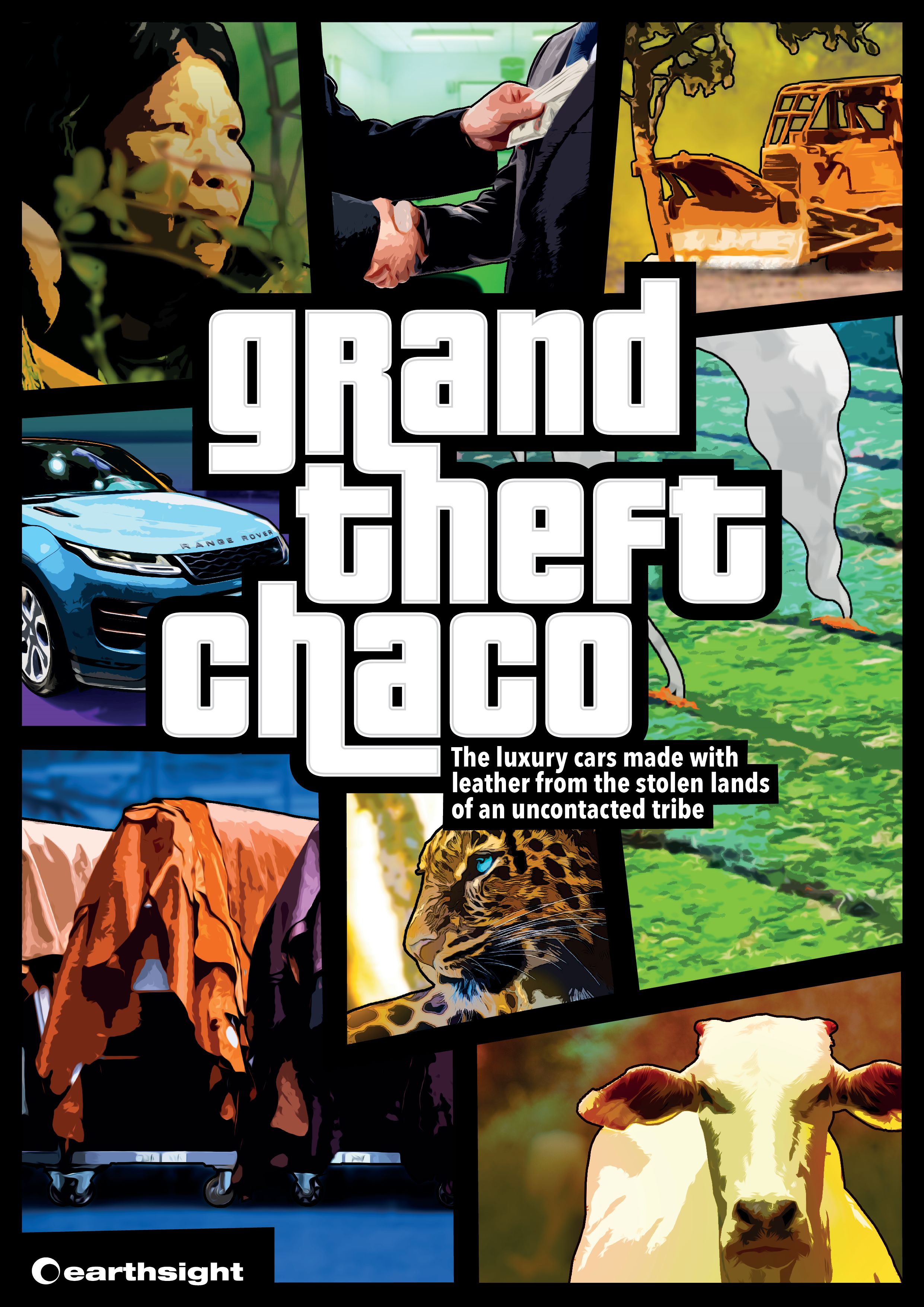

In our report Grand Theft Chaco, Earthsight revealed that European car firms are sourcing leather from slaughterhouses buying cattle from illegally deforested land in Paraguay, a country experiencing some of the highest deforestation rates on earth.

In the course of our investigation, we documented the institutional failings which have left Paraguay’s forests at such high risk.

The body responsible for safeguarding these forests is Paraguay’s environment ministry, MADES.[1] Time and again, MADES officials have turned a blind eye to agribusiness firms clearing forest without authorisation.[2] They have rubber-stamped deforestation on indigenous land, ignoring the protests of affected communities.[3]

These clearances have destroyed some of the last intact expanses of forest inhabited by the Ayoreo Totobiegosode, the only indigenous peoples living in voluntary isolation anywhere in the Americas outside the Amazon rainforest.

To get a sense of what’s happening inside Paraguay’s environment ministry, Earthsight spoke with several of its current and former employees. All described an institutional culture which puts the interests of Paraguay’s landowning class above its environmental law.

One former official, Karen Colman, recounted how she was pushed out of the ministry for challenging this prevailing culture.

© Earthsight

© Earthsight

Illegal deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, December 2019. © Earthsight

Illegal deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, December 2019. © Earthsight

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades © Survival InternationalGAT

The Ayoreo Totobiegosode have been fighting for their land for decades © Survival InternationalGAT

Karen Colman worked as a wildlife technician in Paraguay's environment ministry and has now spoken out about her experiences. © Earthsight

Karen Colman worked as a wildlife technician in Paraguay's environment ministry and has now spoken out about her experiences. © Earthsight

Landowners in Paraguay clear forest often for cattle ranching and other agribusiness activities. © Earthsight

Landowners in Paraguay clear forest often for cattle ranching and other agribusiness activities. © Earthsight

The Chaco forests of Paraguay are rich in biodiversity and home to wildlife such as the giant anteater © Shutterstock

The Chaco forests of Paraguay are rich in biodiversity and home to wildlife such as the giant anteater © Shutterstock

Monkeys, tigers and snakes

A wildlife technician by training, with dark hair and a sharp-eyed refusal to tolerate injustice, Karen joined the ministry’s biodiversity department in 2011. Central to her role was the evaluation of environmental impact assessments: documents submitted by landowners seeking authorisation to clear forest. Karen’s department analysed the potential impact of these projects on wildlife and endangered species.

Shortly after Karen started, a Paraguayan NGO launched a new computer programme tracking deforestation in real time.[4] The programme enabled officials to see how much forest had been cleared on a specific property, and when the clearance had taken place, without having to leave their desk in Asuncion.

Together with a colleague, Karen decided to use the tool to test the veracity of what landowners were telling public officials in their impact assessments. She discovered that many were lying.

“We found that lots of these properties were already cleared of forest,” Karen says. “They were illegal deforestations. The landowners were asking for licenses to regularise what they’d already cut down.”

In some cases, Karen says, property owners had cleared more forest than was allowed in the regulations. In others, they had done so without taking into account the possible presence of endangered species, or neighbouring indigenous communities, or uncontacted indigenous peoples, or any of the other details covered by Paraguay’s environmental law.[5]

Karen talked with her line manager and they decided to denounce what she’d discovered. “I felt excited, like I could finally do something substantial,” she recalls. “Now we can actually change things.”

They began by sending the misleading documents to the ministry’s legal counsel. But the legal counsel ignored them. So, Karen decided to escalate her complaint. “If they’re going to ignore us in the ministry, we’d take it to the public prosecutor,” she says.

Again, her complaint was met with silence. But, never one to be easily dissuaded, Karen continued to send fraudulent folders to the public prosecutor through the following weeks.

Around a month later, Karen was called into the office of the head of environmental quality control, the department ultimately responsible for issuing licenses to landowners. As Karen had been redirecting fraudulent folders to the public prosecutor, they hadn’t been reaching this department - and so landowners weren’t getting the licenses they’d applied for.

The head of control told Karen - “in very fuzzy words” - to stop complaining and allow the licenses to be issued. When she argued, he got angry, and said the wildlife department - which is to say, all the biologists in the ministry - would no longer receive folders to evaluate.

“Until today, no biologists evaluate the folders,” Karen says.

At the same time, pressure for Karen to back down was not only coming from within the ministry. Representatives of the landowners, known as consultants, were also demanding she drop her resistance. One experience was particularly upsetting.

"One day my boss told me I had to attend to a consultant. I went out front, to a corridor in the General Directorate, a narrow corridor between Parks and the rest of the departments. There was no one else there. He asked me why his file wasn't progressing, and I told him that the zone was already deforested. That I couldn't issue a permit to authorise something that was already done - that this is totally illegal. So I had to denounce it.

“Then he came up close to me, too close. I said: 'What's going on? Calm down.' He said to me: 'What is it you want, what do you want?' I just stood there silent, I didn't know what to do, I just wanted to go back to my office. And he took out a bill, tore the bill in half, and put it in my chest. Then he left, saying: 'when you want the other half, let's talk.’

“I cried all that night. I didn't know what to do."

Active deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, December 2019. © Earthsight

Active deforestation in the Paraguayan Chaco, December 2019. © Earthsight

An 'Entrance Prohibited' sign at a cattle ranch in an area of the Paraguayan Chaco exposed to intensive deforestation. © Earthsight

An 'Entrance Prohibited' sign at a cattle ranch in an area of the Paraguayan Chaco exposed to intensive deforestation. © Earthsight

As she had been warned, Karen was stripped of her duties evaluating folders. Instead, she was made to work exclusively in animal rescue: a coati in Asuncion, an anaconda in Ñemby.

One Christmas holiday, she was sent alone to a remote national park to monitor parrot populations for the minimum wage. On another occasion, she had to capture a large male monkey without any protective equipment, which bit and fractured her hand. She realised she could no longer tolerate the job after a day in the pouring rain, trying to convince a circus owner to relinquish his illegal streak of Bengali tigers.

“I started with the idea of wanting to conserve the environment, but I did absolutely none of that in the five years I was there,” Karen reflects. “I achieved absolutely nothing. And the people who were with me in the ministry didn't achieve anything either.”

A museum of biologists

Earthsight verified Karen’s account with two other environment ministry employees who worked with her at the time. The head of the department of wildlife and biodiversity while Karen worked there was Ignacio Avila, now a biologist at the National University of Asuncion.

“Karen was a very good employee, she was always very ethical in whatever she did,” Avila told Earthsight. He recalled frequent clashes between his department and the department of control, responsible for issuing environmental licenses. “It was evident that they worked very much in favour of the producers,” Avila observed.

Since he left in 2013, nearly all the biologists in the ministry have been removed from decision-making positions. They now work solely on research within the Museum of Natural History - which Avila jokingly referred to as a “museum of biologists.”

A current environment ministry employee spoke with Earthsight on condition of anonymity. They described a similar situation, with senior officials repeatedly ignoring flagrant contraventions of Paraguay’s environmental law and employees ordered to approve licenses despite clear irregularities in the associated impact assessments. This employee recalled a senior official telling colleagues: “This is a request from the minister. You have to grant this license.”

The employee described the typical environmental impact assessment submitted by landowners as a “disaster”. “The consultant presents a low-quality impact assessment and the ministry officials are accustomed to evaluating it,” they said. “Ninety per cent of the documents presented by consultants are just copy-and-paste jobs,” the employee added: they change basic data such as location and maps, then copy over the rest. In the overwhelming majority of cases, consultants don’t go to the property to carry out a forestry inventory or check whether changes could impact indigenous land or communities. This is a situation created by the environment ministry, the employee pointed out, which accepts the low-quality work without question - making it difficult for conscientious consultants to compete.

Earthsight talked with officials in Paraguay’s National Forestry Institute (Infona), which is jointly responsible with the environment ministry for managing the country’s forests. The institute’s legal director, Victor Gonzalez, said that so long as the necessary documentation is submitted, officials take a lenient approach to firms clearing forest before authorisation is issued. “In this case we’d classify it more as an administrative fault,” he explained. As long as the landowner has broadly complied with regulations - that is, maintained the requisite forest reserve - “we are very careful about calling it illegal deforestation.”

Such an approach, however, leaves vulnerable groups dangerously exposed. If landowners assume they can clear forest and then regularise the clearances further down the line, they may end up destroying areas that are home to indigenous communities, or isolated tribes, or endangered species.

Cattle ranching is big business and ripe for exploitation in Paraguay. © Earthsight

Cattle ranching is big business and ripe for exploitation in Paraguay. © Earthsight

GD Agronegocios told undercover Earthsight researchers that land clearances could begin without necessary licences. © Earthsight

GD Agronegocios told undercover Earthsight researchers that land clearances could begin without necessary licences. © Earthsight

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegesode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching © Survival InternationalGAT

'Uncontacted’ Ayoreo Totobiegesode forced off their land inside PNCAT in 2004 by cattle ranching © Survival InternationalGAT

These dangers were vividly illustrated by an undercover investigation Earthsight conducted into the murky world of land dealing in Paraguay. Posing as investors interested in cattle ranching, we met with a land broking firm named GD Agronegocios.

The firm’s director assured us that, once we had bought a property and submitted the relevant documentation, we could begin clearing forest straight away - without waiting to receive a license. Sales representatives then offered us two properties located within the territory of the Ayoreo Totobiegosode, where forests protected by Paraguayan law are inhabited by one of the world's last isolated tribes.

“Are there any risks of conflict with local or indigenous communities?” Earthsight asked, innocently. “No, the natives don’t have any problems,” a sales representative replied. “Ten times over: there is no risk.” [6]

Supplied with our draft findings prior to publication of the Grand Theft Chaco report, GD Agronegocios claimed that the properties it offered had legal titles, current use plans and approved environmental impact studies; it said that if prior owners of the properties had acted illegally “it is not a matter for our company”.

The recently installed director of Infona, Cristina Goralewski, told Earthsight that there have been significant problems with the enforcement of environmental regulations. Part of this she put down to the logistical challenges of policing a huge and remote area with the limited resources of the Paraguayan state.

However, she said that a new platform the institute is developing in partnership with Global Forest Watch and the World Resources Institute, which will enable them to remotely monitor deforestation in real time, should make preventing and punishing illegal clearances much easier for her under-resourced officials.

“We think the illegal clearances in the Chaco are a danger for this region, but we also believe that there's an opportunity to develop the Chaco in a sustainable manner,” she said.

But for Karen Colman, tweaking the technology available to staff will do little to bring deforestation under control. Instead, what’s needed is a far more fundamental transformation of the priorities of the Paraguayan government.

“I think the only things that matter here aren’t the people. It's the soya and the cattle. Everything is built on the basis of this in Paraguay," she says.

“Our hospitals don't function, our schools don't function, but our international roads yes they function because they transport cattle. Our economy doesn't function but we have the lowest meat export taxes in South America, yes this functions. We have the best genetic technology, not to cure genetic diseases, but to improve cattle. Everything revolves around those two questions, soya and cattle. And ultimately the soya is to feed the cattle.”

Paraguay's environment ministry did not respond to requests for comment.

Karen's story: The full film

Watch in Spanish: